Macro Letter – No 58 – 08-07-2016

China – Rebalancing, Debt and the Stock Market

- Chinese growth has been slowing since 2007

- Total debt to GDP has risen from 148% in 2007 to 237% today

- Oversupply in real-estate is still a concern but lower interest rates are helping

- Infrastructure spending may help and Chinese stocks are cheap

I was prompted to write this rather longer letter by the recent weakness of the Chinese currency. The chart below tracks the progress of the USDCNY over the last three years, compared with many emerging markets the devaluation is minimal:-

Source: Trading Economics

A longer term chart shows how far the currency has travelled over the last 12 years:-

Source: Trading Economics

It was at the National People’s Congress of March 2013 that the policy of “rebalancing” was introduced, however, the CNY continued to strengthen. This gradual appreciation against the US$ had created large imbalances within the Chinese economy. The economic-policy adjustment of “rebalancing” had one objective: shifting China from a production-oriented economy to one focused on household consumption. If, in the process, it could alleviate international pressure on the Chinese administration to allow the CNY to float freely, so much the better. Now it looks as if the outcome of allowing the CNY to float freely would see it sink like a stone.

A Review of Rebalancing

A detailed analysis of the rebalancing challenge is contained in this February 2013 paper from the ECB – China’s Economic Growth and Rebalancing it highlights international concerns:-

China’s leadership is well aware of the limitations of the producer-biased and export-led model. Interestingly, there is no major disagreement between the Chinese and the international community about the need for rebalancing policies to ensure China’s smooth transition to a more sustainable model. The disagreement is more about how fast the reform measures should be implemented.

It has been argued that intertwined economic and political interests make China’s rebalancing more difficult and cause the reform process to advance slowly. Political resistance to the reforms stems from various sources. First, in a system where political success at the local level has been historically dependent on quantitative growth, reforms that emphasise the quality of growth are bound to meet some resistance. Second, the current growth model required to keep some strategic sectors of the economy closed and under state control (e.g. financial markets, services, heavy industry). The planned opening up of these sectors to competition does not only meet resistance from SOEs and banks, but is also questioned in government circles owing to worries about exhausting the “privilege” of direct macroeconomic policy management. Not surprisingly, major resistance is observed in the export lobby, which is one of the most influential in China and the one which reforms affect most directly.

Reviewing the policy initiative in June 2014 – shortly after the, once in a decade, handover of power from President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao to Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang – McKinsey – China’s great rebalancing: Promise and peril concluded:-

Of course, there is no guarantee that rebalancing will succeed. Part of the problem is that the politics associated with it—boosting the income of Chinese households at the expense of state-owned companies and other large investment-oriented entities—is actually more complicated than the economics. But one thing is certain. China is rapidly reaching the point of diminishing economic and political returns from its investment-driven model, which is headed for change one way or another: either through a proactive rebalancing, with reforms and policy adjustments, or a forced rebalancing precipitated by rising stresses in and beyond the financial system. So far, the signs are encouraging that the new leadership is serious about changing China’s growth model, and this is reason enough for global firms that have benefited from China’s investment boom to rethink their strategies for the years ahead.

Three years on the challenges of rebalancing an $11trln economy of 1.4bln people are becoming evident. McKinsey – China’s Choice – Capturing the $5 Trillion Productivity Opportunity, published last month, makes the case for continued reform based on boosting productivity:-

…Government can do a great deal to improve the odds of success by transforming institutions in six priority areas:

I. Open more sectors up to competition. SOEs still account for 43 percent of service sector fixed-asset investment, compared with 8 percent in manufacturing

.…In telecommunications, for instance, an effort to introduce mobile virtual network operators to target underserved segments has not yet had a substantial impact because the big three players in the sector still have considerable clout in negotiations and strong influence on pricing. In health care, fixing the economics model to make hospitals less dependent on drug sales and encourage more qualified doctors to work at private hospitals could help improve the quality of service.

II. Improve the breadth and quality of capital markets. China would benefit from a financial system where market forces allocate capital efficiently; that means well functioning bond and equity markets that attract a diverse set of investors, including institutional and overseas players. The municipal bond market could lower financing costs for local government while bringing market discipline to managing investment projects. To facilitate this shift, China needs to strengthen the foundations of an effective financial system, such as strong, independent credit-rating agencies, more transparent public data on the economy, and more effective communication about government monetary policy. Inviting new players (such as internet banks) to supply capital and helping banks build capabilities to undertake more lending for underserved segments such as small and medium-sized enterprises and rural consumers will be important.

III. Enable corporate restructuring. Shifting successfully to a productivity-led growth model will mean a sea change—letting inefficient companies fail rather than protecting and propping them up and rationalizing excess capacity.

…enforcing bankruptcy law and improving the bankruptcy process. Strengthening capabilities of asset-management companies tasked with handling restructuring could help to turn around companies in default. China will need to expand the securitization of non-performing loans to be prepared for any larger-scale bad debt situation and to ensure that banks put effective risk management in place.

IV. Invest in talent and enhance labor mobility. China has made great strides in educating its people, but more is needed. Among the measures that the government could now take are providing more funding for education, designing programs that rotate effective teachers to places they are most needed, and engaging the private sector to define job-ready skills, build those into curricula, and establish an education to-employment pipeline. On top of this, the government could enhance labor mobility to optimize employment across different regions of the country. Expansion of unemployment insurance and training can help smooth the transition for displaced workers and help them back into jobs. Ensuring gender equality in opportunities in education and in the labor market, while supporting women as well as men as they develop their careers, can further strengthen China’s talent base.

V. Boost aggregate demand. As inequality grows, the government can revise fiscal and tax policies to give households more spending power. For families in need, it could consider conditional cash transfers. Improving social safety net programs by raising health-care and retirement benefits, for example, can reduce the need for precautionary saving for out-of-pocket medical expenses, facilitate consumption, and reduce income inequality. Broadening affordable-housing programs to include migrant workers, with market-based subsidies on both the supply and demand side, can also help low-income families to consume more.

VI. Improve public-sector effectiveness. Ensuring that government raises its own productivity is an important part of any transition to a productivity-led model. Such an effort can start by using household income and productivity indicators to evaluate officials and departments rather than rewarding them largely for the GDP growth their cities or regions achieve. Digitizing government operations and service delivery is an important part of the mix. Government also needs to develop better conflict-resolution capabilities to mediate between different stakeholders so that restructuring and reforms can proceed.

Another aspect of President Xi’s reform is in foreign policy, it has been dubbed the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR). Last week the Economist – Our bulldozers, our rules discussed the potential of the initiative:-

…Asia needs new infrastructure—about $770 billion a year of it until 2020, according to the Asian Development Bank. This demand should eventually ease today’s worries about a lack of projects. Bert Hofman, the World Bank’s chief in Beijing, adds that individual countries will benefit more if they align their plans with one another and with China. It does not pay to plan and build separately.

Next, China needs OBOR. At home, its businesses are being squeezed by rising costs and growing demands that they pay more attention to protecting the environment. It makes sense for them to shift some manufacturing overseas—as long as the infrastructure is there.

Lastly, Xi Jinping needs it. He has made OBOR such a central part of his foreign policy and has gone to such lengths to swing the bureaucracy behind the project that it is too late to step back now.

None of this means the new Silk Road will be efficient, nor does it mean China’s plans will always be welcome in countries suspicious of its expanding reach. But the building blocks are in place. The first projects are up and running. OBOR is already beginning to challenge the notion of Europe and Asia existing side by side as different trading blocs.

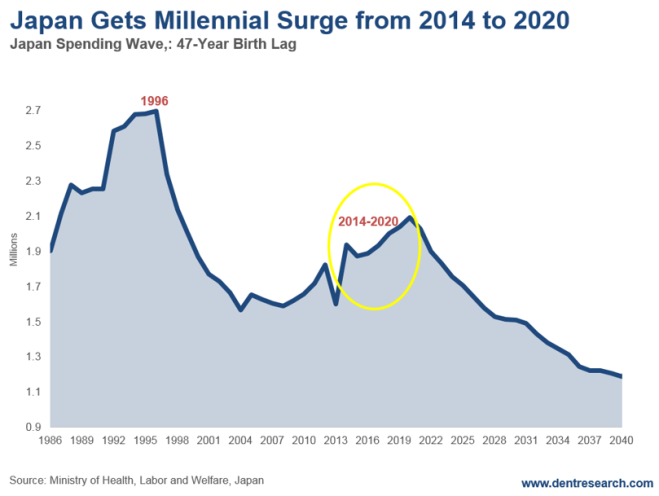

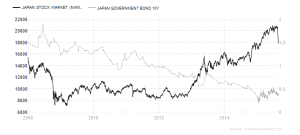

This is reminiscent of the economic development of Japan during the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Despite these policy initiatives, the Chinese economy has been slowing for the past six years. An excellent overview of the current situation was provided last month by the China-United States Exchange Foundation – China’s Incomplete Growth Strategy, in which they highlighted the policies for and challenges to achieve growth, both in the long and short run. Most of the problems are associated with the oversupply evident in the real-estate market and the economic drag from the debt associated with this over-supply. Their solution, as McKinsey suggested above, is infrastructure development:-

…last November, they officially placed the blame on long-term supply-side shortcomings, which they pledged to address with far-reaching structural reforms.

…the supply-side focus largely ignores the present. China faces two separate challenges: the long-term issue of a declining potential growth rate and the immediate problem of below-potential actual growth.

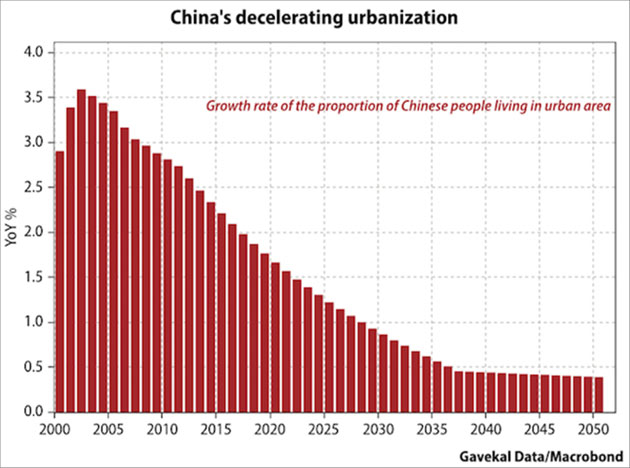

Among the long-term factors undermining potential growth are diminishing returns to scale, a widening income gap, and a narrowing scope for technological catch-up through imitation. Moreover, even as the country’s demographic dividend dissolves, its carrying capacity (the size of the population the environment can sustain) is being exhausted – a situation that high levels of pollution are certainly not helping. Finally, and most important, the country is suffering from inadequate progress on market-orientated reform.

While some of these factors are irreversible, others can be addressed effectively. And, indeed, the government’s supply-side reform strategy will go a long way toward doing just that, ultimately stabilizing and even raising China’s growth potential. But, contrary to popular belief, they will not boost China’s actual growth rate today.

Why are so many economists convinced that a long-term reform strategy is all China needs? One reason is the widely held notion that today’s overcapacity reflects supply-side problems, not insufficient demand. According to this view, China should implement policies like tax cuts to encourage companies to produce products for which there is genuine demand. That way, the government would not inadvertently sustain “zombie enterprises” that cannot survive without bank loans and support from local governments.

But only some of China’s overcapacity can be attributed to bad investment decisions. A large share has emerged because of a lack of effective demand. And that is, at least partly, a result of the government’s effort to moderate real-estate investment, which has caused the sector’s annual growth to tank, plunging from 38% in 2010 to 1% at the end of 2015.

With real-estate investment still accounting for more than 14% of GDP last year, plummeting growth in the sector has put considerable downward pressure on the economy as a whole, helping to push China into a debt-deflation spiral. As overcapacity drives down the producer price index – which has now been falling for 51 consecutive months – real debt rises. This is undermining corporate profitability, spurring companies to deleverage and reduce investment, and fuelling further declines in PPI.

The enduring importance of real-estate investment to China’s economic growth is reflected in trends from the first quarter of this year. Annual GDP growth of 6.7%, despite being the slowest rate for any quarter in seven years, exceeded market expectations. And it was driven partly by an unforeseen increase in real-estate investment growth, to 6%.

This is not to say that what China needs is more real-estate investment. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China had 718 million square meters of unsold commercial and residential floor space at the end of 2015; when space under construction is factored in, inventory expands to more than five billion square meters. With an average of only 1.2 billion square meters of housing being sold each year, the best way to reduce this supply glut is clear: limit future construction. One of the most important reasons for the recent investment surge was abundant liquidity driving speculative demand – and that is hardly sustainable.

…Infrastructure investment, in particular, may well be the key to tackling China’s economic woes. After all, such investment, which grew at 19.6% in the first quarter of 2016, has already proved to be a critical driver of economic growth – and, unlike real-estate investment, it has not worsened China’s resource allocation or set the stage for major imbalances.

When there is slack in the economy, the only way to escape the debt-deflation trap is to grow strongly. Given that China is saddled with large local-government and corporate debts, but also enjoys large domestic savings and a strong fiscal position, this message could not be more pertinent. In an ideal world, domestic consumption would serve as the main engine of growth; under current circumstances, infrastructure investment is the most reliable option.

In the short term, when overcapacity and deflation are the main obstacles, infrastructure investment boosts growth through the economy’s demand side. In the long run, it operates through the supply side to boost productivity and thus raise growth potential. China can fund such investment with fiscal deficits, given strong demand for government bonds. And, with China’s major banks still state-owned, and capital controls still in place, the risk of an imminent financial crisis is very low.

Of course, China’s government must uphold its commitment to implement structural reforms. But infrastructure investment is also badly needed, not just to prevent the economy from sliding further, but also to enable China to generate the sustained long-term growth that it requires to achieve developed-country status.

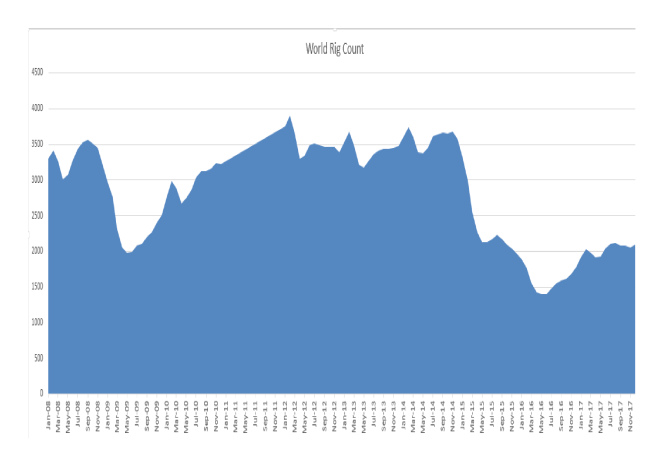

The slowdown in Chinese growth has finally prompted concerns around the world. In their May Economic Letter, the Dallas Fed – Impact of Chinese Slowdown on U.S. No Longer Negligible noted that the knock on effect of slowing Chinese growth had taken 20% off US GDP. The chart below shows Chinese and US annual GDP growth over the last 10 years, China is the left hand scale, the negative impact of Chinese growth on US GDP since 2010 has been roughly 0.4%:-

Source: Trading Economics

The Problem of Debt

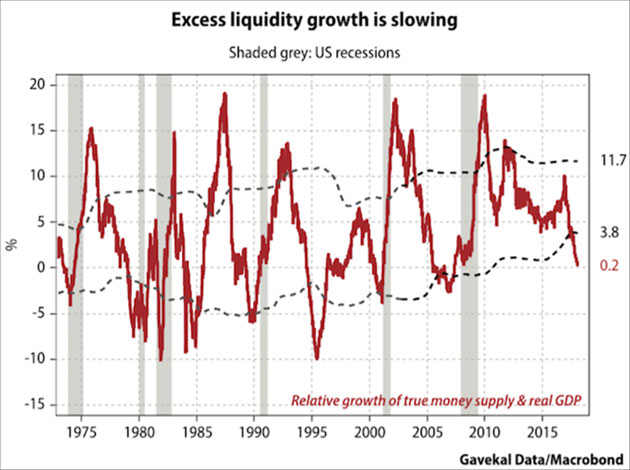

The current environment in China – as it is in much of the rest of the world – is dominated by the incessant increase in debt. In May, in what many observers regard to be a reversal of their opinion on the dangers of China’s debt mountain, the Economist – The coming debt bust attempted to quantify the magnitude of the problem facing the Chinese financial system:-

China was right to turn on the credit taps to prop up growth after the global financial crisis. It was wrong not to turn them off again. The country’s debt has increased just as quickly over the past two years as in the two years after the 2008 crunch. Its debt-to-GDP ratio has soared from 150% to nearly 260% over a decade, the kind of surge that is usually followed by a financial bust or an abrupt slowdown.

China will not be an exception to that rule. Problem loans have doubled in two years and, officially, are already 5.5% of banks’ total lending. The reality is grimmer. Roughly two-fifths of new debt is swallowed by interest on existing loans; in 2014, 16% of the 1,000 biggest Chinese firms owed more in interest than they earned before tax. China requires more and more credit to generate less and less growth: it now takes nearly four yuan of new borrowing to generate one yuan of additional GDP, up from just over one yuan of credit before the financial crisis. With the government’s connivance, debt levels can probably keep climbing for a while, perhaps even for a few more years. But not for ever.

When the debt cycle turns, both asset prices and the real economy will be in for a shock. That won’t be fun for anyone. It is true that China has been fastidious in capping its external liabilities (it is a net creditor). Its dangers are home-made. But the damage from a big Chinese credit blow-up would still be immense. China is the world’s second-biggest economy; its banking sector is the biggest, with assets equivalent to 40% of global GDP. Its stockmarkets, even after last year’s crash, are together worth $6 trillion, second only to America’s. And its bond market, at $7.5 trillion, is the world’s third-biggest and growing fast. A mere 2% devaluation of the yuan last summer sent global stockmarkets crashing; a bigger bust would do far worse. A mild economic slowdown caused trouble for commodity exporters around the world; a hard landing would be painful for all those who benefit from Chinese demand.

Brace, brace

Optimists have drawn comfort from two ideas. First, over three-plus decades of reform, China’s officials have consistently shown that once they identified problems, they had the will and skill to fix them. Second, control of the financial system—the state owns the major banks and most of their biggest debtors—gave them time to clean things up.

Both these sources of comfort are fading away. This is a government not so much guiding events as struggling to keep up with them. In the past year alone, China has spent nearly $200 billion to prop up the stockmarket; $65 billion of bank loans have gone bad; financial frauds have cost investors at least $20 billion; and $600 billion of capital has left the country. To help pump up growth, officials have inflated a property bubble. Debt is still expanding twice as fast as the economy.

…“shadow assets” have increased by more than 30% annually over the past three years. In theory, shadow banks diversify sources of credit and spread risk away from the regular banks. In practice, the lines between the shadow and formal banking systems are badly blurred.

That creates two risks. The first is higher-than-expected losses for the banks. Hungry for profits in a slowing economy, plenty of Chinese banks have mis-categorised risky loans as investments to dodge scrutiny and lessen capital requirements. These shadow loans were worth roughly 16% of standard loans in mid-2015, up from just 4% in 2012. The second risk is liquidity. The banks have become ever more reliant on “wealth management products”, whereby they pay higher rates for what are, in effect, short-term deposits and put them into longer-term assets. For years China restricted bank loans to less than 75% of their deposit base, ensuring that they had plenty of cash in reserve. Now the real level is nearing 100%, a threshold where a sudden shortage in funding—the classic precursor to banking crises—is well within the realm of possibility. Midsized banks have been the most active in expanding; they are the place to look for sudden trouble.

Pandamonium

The end to China’s debt build-up would not look exactly like past financial blow-ups. China’s shadow-banking system is big, but it has not spawned any products nearly as complex or international in reach as America’s bundles of subprime mortgages in 2008. Its relatively insulated financial system means that parallels with the 1997-98 Asian crisis, in which countries from Thailand to South Korea borrowed too much from abroad, are thin. Some worry that China will look like Japan in the 1990s, slowly grinding towards stagnation. But its financial system is more chaotic, with more pressure for capital outflows, than was Japan’s; a Chinese crisis is likely to be sharper and more sudden than Japan’s chronic malaise.

One thing is certain. The longer China delays a reckoning with its problems, the more severe the eventual consequences will be. For a start, it should plan for turmoil. Policy co-ordination was appalling during last year’s stockmarket crash; regulators must work out in advance who monitors what and prepare emergency responses. Rather than deploying both fiscal and monetary stimulus to keep growth above the official target of at least 6.5% this year (which is, in any event, unnecessarily fast), the government should save its firepower for a real calamity. The central bank should also put on ice its plans to internationalise the yuan; a premature opening of the capital account would lead only to big outflows and bigger trouble, when the financial system is already on shaky ground.

Most important, China must start to curb the relentless rise of debt. The assumption that the government of Xi Jinping will keep bailing out its banks, borrowers and depositors is pervasive—and not just in China itself. It must tolerate more defaults, close failed companies and let growth sag. This will be tough, but it is too late for China to avoid pain. The task now is to avert something far worse.

An article in Bruegal – Chinese banks: the way forward, which was published in April, looks in greater detail at the expansion of Chinese bank credit:-

The extensive credit expansion in January and February, especially from the banking sector, has several implications. First, it masks the growth of the non-performing loan ratio as the denominator has experienced such a big increase. Second, such surge in credit granted must have had a surge in demand as well. Whether that new demand reflects an improvement in the economy or simply more financing needs is a key question. If it is the latter then it reflects an increasing demand for new funds to repay outstanding loans.

Having said that, China had a bad-loan coverage ratio of 150%, which is considered high for international standards. However, there is rumor that this will be lowered to 120%. In any event, credit risk is rapidly rising in China as the economy slows down and financial conditions are lax enough for corporates to continue to leverage. The question, thus, is how weak are Chinese banks in the current circumstances.

No review of the financial position of China would be complete without a comment from Michael Pettis; last month he wrote Rebalancing, wealth transfers, and the growth of Chinese debt, this is a long research paper so I have only included extracts below:-

There is no way Beijing can address the debt without a sharp drop in GDP growth, but as unwilling as Beijing may be to see much lower growth, it doesn’t have any other option. It must choose either much lower but manageable growth today or a chaotic decline in growth tomorrow. The debt burden cannot stop rising, in other words, until Beijing adjusts its growth expectations sharply downwards and forcefully implements the kinds of reforms that the XI administration has talked about implementing, albeit against powerful political opposition, since the Third Plenum of October 2013.

Pettis then produces a set of scenarios, firstly with growth remaining at current levels:-

| Growth remains at 6-7% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| No government transfers

|

· Debt growth is steady at 12-14%

· Investment growth is steady at current levels

· Consumption growth is steady at current levels

· Growth in household income is steady and household share of GDP is unchanged

· No rebalancing

|

· Period begins with 25% higher debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption and investment account for roughly equal shares of GDP

· Debt growth rises to 15-18%

· Investment growth is steady at current levels

· Consumption growth is steady at current levels

· Growth in household income is steady and household share of GDP is unchanged

· No rebalancing |

| Growth remains at 6-7% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| Annual government transfers of 1-2% of GDP

|

· Debt growth drops to 9-10%

· Investment growth declines by 2-3 percentage points

· Consumption growth rises by 2-3 percentage points

· Growth in household income rises by 2-3 percentage points and household share of GDP rises slightly

· Minimal rebalancing

|

· Period begins with 10-15% higher debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption exceeds investment as a source of growth

· Debt growth rises to 11-13%

· Investment growth declines by another percentage point

· Consumption growth is steady

· Growth in household income is steady and household share of GDP rises

· Gradual rebalancing |

| Growth remains at 6-7% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| Annual government transfers of 3-4% of GDP

|

· Debt growth drops to 8-10%

· Investment growth declines by 6-7 percentage points

· Consumption growth rises by 6-7 percentage points

· Growth in household income rises by 6-7 percentage points and household share of GDP is materially higher

· Material rebalancing

|

· Period begins with 5-10% higher debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption significantly exceeds investment as a source of growth

· Debt growth rises to 6-8%

· Consumption growth declines by 1-2 percentage points

· Growth in household income declines by 1-2 percentage points and household share of GDP is materially higher

· Material rebalancing

|

Next, Pettis looks at the same scenarios adjusting growth lower:-

| Growth drops to 3-4% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| No government transfers

|

· Debt growth drops to 6-8%

· Investment growth declines by 4-6 percentage points

· Consumption growth declines by 2-4 percentage points

· Growth in household income declines by 2-4 percentage points and household share of GDP is slightly higher

· Material rebalancing

|

· Period begins with 10-15% higher debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption exceeds investment as a source of growth

· Debt growth is steady at 6-8%

· Investment growth is steady at current levels

· Consumption growth is steady at current levels

· Growth in household income is steady at current levels and household share of GDP is materially higher

· Material rebalancing |

| Growth drops to 3-4% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| Annual government transfers of 1-2% of GDP

|

· Debt growth drops to 5-6%

· Investment growth declines by 7-9 percentage points

· Consumption growth is flat

· Growth in household income is flat and household share of GDP is higher

· Material rebalancing

|

· Period begins with slightly higher debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption significantly exceeds investment as a source of growth

· Debt growth is steady at 5-6%

· Investment growth is steady at current levels

· Consumption growth is steady at current levels

· Growth in household income is steady at current levels and household share of GDP is materially higher

· Material rebalancing

|

| Growth drops to 3-4% |

2016 -2019 |

2020-2023 |

| Annual government transfers of 3-4% of GDP

|

· Debt growth drops to close to zero

· Investment growth is zero

· Consumption growth rises from current levels

· Growth in household income rises from current levels and household share of GDP is materially higher

· Substantial rebalancing

|

· Period begins with lower debt-to-GDP ratio, and consumption significantly exceeds investment as a source of growth

· Debt growth drops to well below GDP growth

· Investment growth is steady at current levels

· Consumption growth is steady at current levels

· Growth in household income is steady at current levels and household share of GDP is substantially higher

· Substantial rebalancing |

Pettis concludes:-

A massive debt burden significantly reduces the options available to policy-makers and a severely unbalanced structure of demand forces policy-makers to choose between rising unemployment, rising debt, or rising wealth transfers. Economists who do not understand how this fairly simply trade-off dominates all policymaking simply will not be able to provide useful policy advice.

Conclusion and Investment Opportunities

China, like many other countries has a problem with debt. The FT recently published an estimate that the Chinese debt to GDP ratio was only 237% (lower than the Economist’s 260%) and government debt to GDP is only 43.9%, whilst household debt to GDP is 39.5%. The Heritage Foundation – Index of Economic Freedom 2016 – estimates China’s government spending to GDP at 29.3%, below that of many developed nations. The Rahn curve below shows how government spending can help to accelerate growth but the diminishing return once it rises above 15% of GDP:-

Source: The Heritage Foundation, Peter Brimelow

Nonetheless, China compares favourably with Japan where government spending is 40.2%.

Stocks, Bonds and the Currency

The Shanghai Composite, shown below, has turned higher since the middle of May. A break above 3,075 could see it retest the highs of 2015 but this is unlikely to be the policy of the Xi administration:-

Source: Trading Economics, Shanghai Stock Exchange

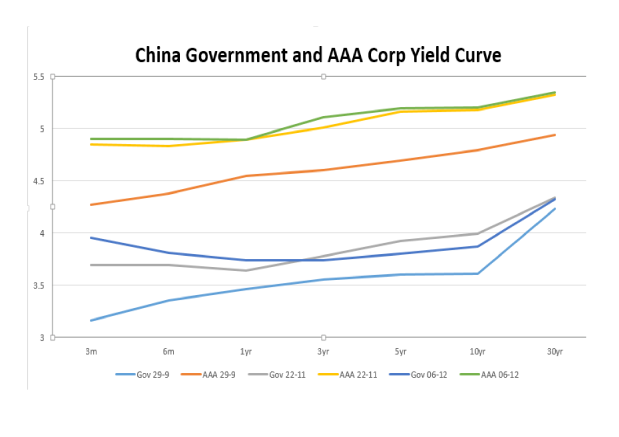

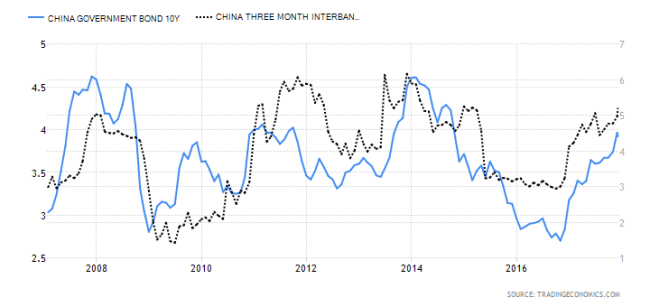

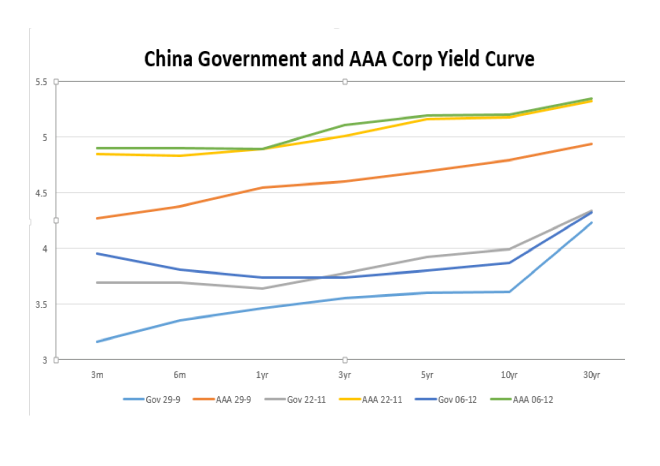

10 year Chinese Government bonds have declined in yield as a result of the international turmoil created by Brexit, but, unlike many of major, international government bonds, they have not made new lows so far:-

Source: Trading Economics, Chinese Ministry of Finance

I believe the recent rally in stocks is a function of the lower yield on bonds. The Chinese government has the whip hand. During the rally and subsequent collapse in the stock market during 2015, the government did not respond in a coordinated manner. Amongst a plethora of initiatives, and I may well have missed some, they relaxed margin requirements, fuelling the speculative bubble, then, as the shake out gathered momentum, suspended the trading in shares listed on multiple markets. As liquidity conditions became more severe they froze 38 individual trading accounts – including certain algorithmic liquidity providers. The regulators also banned short selling and margin loans enabling investors to sell short on T=) settlement. They forced certain brokers to execute buy orders; one broker was bailed out with a CNY 260bln cash injection.

The rules on insurance companies purchasing stock were relaxed, certain shareholders (specifically SOE’s) were prohibited from selling and, under Announcement 18, senior managers and major shareholder (ones holding a stake of 5 % or more) were threatened with “severe punishment” if they sold shares of any listed company during a period of six months. IPO issuance was also suspended – a recent article from the FRBSF – China’s IPO Activity and Equity Market Volatility looks at possible reforms of the IPO market. The authorities will not want to make the same mistakes a second time.

Margin lending has, so far, remained subdued. The chart below has data up to March 2016. Chinese investors were wounded last year but 10 year bond yields have fallen 80bp since June 2015:-

Source: Wind Information Co, WSJ

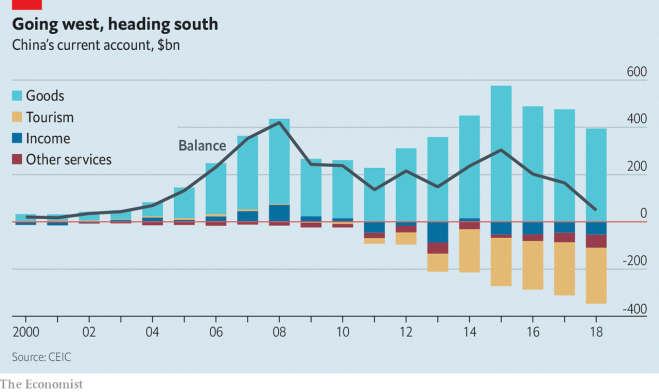

Returning to the first chart, tracing the fortunes of the CNY, China appears to be exporting its way out of trouble at the expense of its trading partners. Its largest export market is the EU, US followed by Japan and South Korea. Here is the US census bureau data for US-China trade since 2008:-

| Month |

Exports |

Imports |

Balance |

| Jan-16 |

8212 |

37146 |

-28934 |

| Feb-16 |

8049 |

36161 |

-28112 |

| Mar-16 |

8952 |

29853 |

-20901 |

| Apr-16 |

8667 |

32973 |

-24306 |

| May-16 |

8518 |

37535 |

-29017 |

|

|

|

|

| Month |

Exports |

Imports |

Balance |

| Jan-15 |

9482 |

38588 |

-29107 |

| Feb-15 |

8759 |

31574 |

-22814 |

| Mar-15 |

9882 |

41139 |

-31257 |

| Apr-15 |

9307 |

36116 |

-26809 |

| May-15 |

8763 |

39073 |

-30310 |

| Jun-15 |

9622 |

41455 |

-31833 |

| Jul-15 |

9514 |

41216 |

-31703 |

| Aug-15 |

9169 |

44142 |

-34973 |

| Sep-15 |

9424 |

45718 |

-36294 |

| Oct-15 |

11410 |

44319 |

-32908 |

| Nov-15 |

10618 |

41908 |

-31290 |

| Dec-15 |

10122 |

37996 |

-27874 |

| Year |

|

|

|

| 2015 |

116072 |

483245 |

-367173 |

| 2014 |

123621 |

468484 |

-344863 |

| 2013 |

121746 |

440430 |

-318684 |

| 2012 |

110517 |

425619 |

-315103 |

| 2011 |

104122 |

399371 |

-295250 |

| 2010 |

91911 |

364953 |

-273042 |

| 2009 |

69497 |

296374 |

-226877 |

| 2008 |

69733 |

337773 |

-268040 |

Source: US Census Bureau

To help stem the decline in Chinese growth the National Bureau of Statistics has revised the way it calculates GDP. Zero Hedge – China To Boost “Economic Growth” By Changing Definition Of GDP quotes Yu Song of Goldman Sachs:-

Under the new method, the size of the economy is larger than previously estimated; 2015 GDP was revised up by 1.3% to 11tn USD, the Real growth rate was also revised up (rates vary from year to year and averaged 0.06% (6 bps) over the past 5 years). The upward revision is because China’s R&D expenditure growth has been consistently faster than that of overall GDP–though the difference the change makes to the GDP growth rate is small as R&D is a small part of the economy. The NBS announced 1Q real growth was revised up by 0.04% (4bps), but it did not specify whether the growth rate is now 6.8% yoy or remains at 6.7% yoy. We believe the latter case is slightly more likely as an upward revision would have been highlighted. A higher trend level would mean 2Q GDP growth should be higher as well. As a result, we revise our Q2 real GDP growth forecast to 6.7% yoy from 6.6% yoy previously with slight upside risk to our full-year forecast of 6.6% yoy.

Whether the markets are taken in by this sleight of hand remains to be seen, but, when statisticians are making comparisons in a couple of years from now, the higher growth rate will most likely be taken as gospel.

State Owned Enterprises are investing even as the private sector continues to withdraw – Reuters – China needs the private sector to step up. Residential and commercial construction continues to grow despite 718 M2 of vacant floor space. It is worth remembering that 75% of Chinese individual net worth is tied up in Real-Estate – in the US the figure is 28%. Lagarde’s second in command, David Lipton, of the IMF said China had made only “limited progress” in reducing its debt load but government bonds are near historic lows, making non-performing loans easier to extend. Back in the summer of 2014 I wrote about the importance of the housing market – Macro Letter – No 18 – 29-08-2014 – The second arrow of Likonomics and the Chinese property market, the stock market subsequently rallied but then collapsed. Now the policy of “rebalancing” seems to be taking a breather.

Chinese stocks, meanwhile, are cheap relative to many other markets. As at the end of June the CAPE was 12.4, PE 6.1 – the lowest of any major stock market globally, PC 3.2, PB 0.8, PS 0.6 and the dividend yield was 4.7%. Only the differential between the dividend yield and the 10 year bond yield (1.93%) looks unremarkable.

Chinese Q2 GDP data is released next week, an unnamed official suggested the PBoC might still have room to cut interest rates, although any further loosening of bank reserve requirements appears unlikely. As we head into the summer lull, Chinese stocks, especially those with an exposure to infrastructure, may offer an excellent buying opportunity.