During the last three months inflation has become a much debated topic. This article, which was published in March, may still add something to the increasingly heated debate: –

Inflationary Inflection Point or Temporary Blip?

Macro Letter – No 139 – 18-06-2021

Commodities, Supply-chains and Structural Changes in Demand

As the spectre of inflation begins to haunt economists, many market commentators have started to focus on commodity prices in an attempt to predict the likely direction of the general price level for goods and services. This indexing of the most heterogeneous asset class has always struck me as destined to disappoint. Commodity prices change in response to, often, small variation in supply or demand and the price of some commodities varies enormously from one geographic location to another. Occasionally the majority of commodities rise in tandem but more frequently they dance to their own peculiar tunes.

Commodity analysts tend to focus on Energy and Industrial Metals foremost; Agricultural Commodities, which are more diverse by nature are often left as a footnote. Occasionally, however, a demand-side event occurs which causes nearly all sectors to rise. The Covid-19 event was just such a shock, disrupting global supply-chains and consumer demand patterns simultaneously.

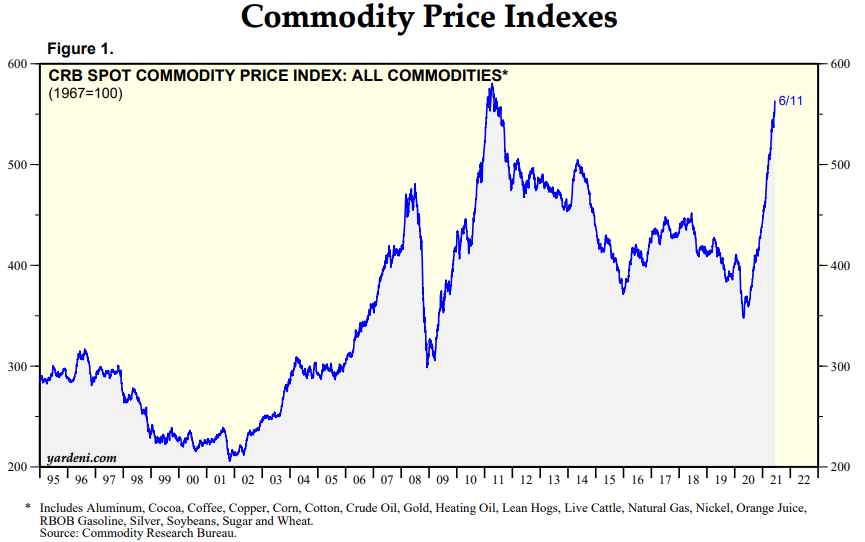

The chart below shows the CRB Index since 1995: –

Source: CRB, Yardeni

This chart looks very different to the energy heavy GSCI Index, which is weighted on the basis of liquidity and by the respective world production quantities of its underlying components: –

Source: S&P GSCI, Trading Economics

The small rebound on the chart above is not that insignificant, however, it equates to a 55% rise since the lows on 2020. The fact that prices collapsed, as the pandemic broke, and subsequently soared, as vaccines allowed economies to reopen, is hardly surprising. Economic cycles wield a powerful influence over commodity prices; short-term, inelastic, supply, confronted by an unexpected jump in demand, invariably precipitates sharp price increases.

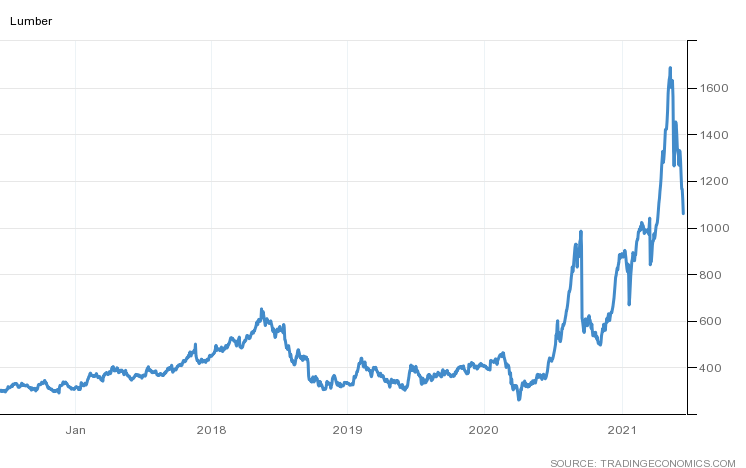

The lockdown which followed the initial outbreak of the virus, led to an abrupt change in consumer demand; hotels and travel were out, remote working was in. Whilst house prices were already supported by a sharp lowering of interest rates and debt forbearance measures, the price of lumber, for home improvements and property extensions, exploded: –

Source: Trading Economics

Similar patterns were evident in Steel and Copper, but also due to shortages and bottlenecks in the semiconductor supply-chain, which led a slowing of automobile production, in turn prompting a rise in the price of both for new and used cars.

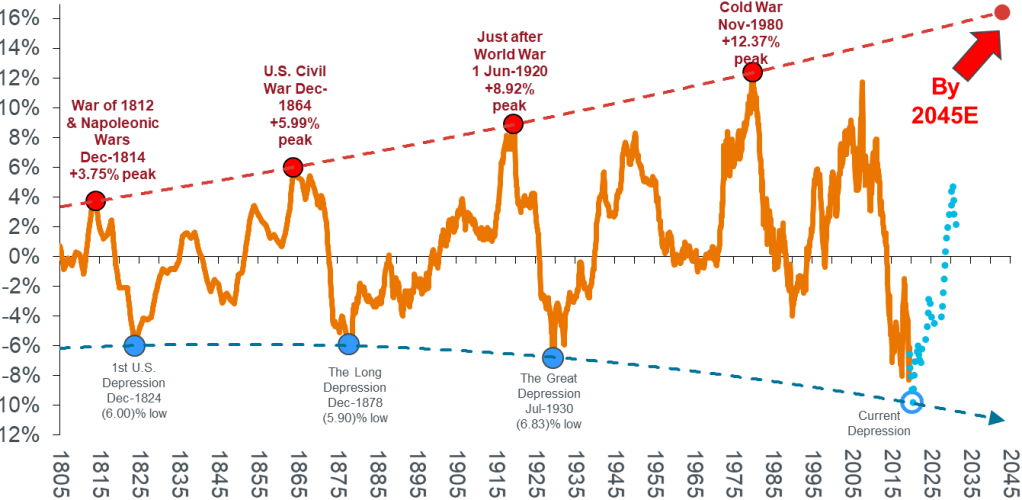

The recent resurgence in commodity prices has encouraged suggestions that a new commodity super-cycle is underway, however, these are relatively rare events. The most recent cycle is generally thought to have begun with the rise of Chinese demand in the late 1990’s and ended abruptly with the financial crisis in 2008/2009. Since the crisis Chinese growth has moderated, although the rise of India may see another wave of rapid industrialisation at some point. The chart below, however, portrays a different narrative, suggesting that the 2008 peak was merely a corrective wave from the 1980 peak. The new super-cycle has just begun, it will peak some-time around 2045: –

Source: Janus Henderson, Stifel Report June 2020. Note: Shown as 10yr rolling compound growth rate with polynomial trend at tops and bottoms. Blue dotted line illustrates a forecast estimation. Warren & Pearson Commodity Index (1795-1912), WPI Commodities (1913-1925), equal-weighted (1/3rd ea.) PPI Energy, PPI Farm Products and PPI Metals (Ferrous and Non-Ferrous) ex-precious metals (1926-1956), Refinitiv Equal Weight (CCI) Index (1956-1994), and Refinitiv Core Commodity CRB Index (1994 to present).

Another short-term factor, which has exacerbated the rise in the price of key commodities over the past year, is the ongoing trade tensions between the US and China. Tariff increases have increased costs for importers and wholesalers, meanwhile the effect of the Great Financial Crisis has been evident for the past decade in the shortening of global supply-chains. Covid accelerated this de-globalisation, forcing many firms to seek out new sources of supply. The long-run effect of these adjustments will be stronger, deeper supply-chains, but the short-run cost must be paid for by the importer, the producer or the consumer.

A part of the new commodity super-cycle argument is based on more structural factors. The reduction of carbon emissions will entail the use of vast amounts of metals. Electrification calls for copper; silver will be needed for photovoltaic panels; electric vehicles require aluminium, nickel, graphite, cobalt and lithium, together with numerous rare-earth metals – of which China is fast becoming the monopoly supplier.

The last great structural shift in energy was from coal to oil. Colonel Drake’s discovery in Pennsylvania in 1859 and the Spindletop find in Texas in 1901 set the stage for the new oil economy, yet it took until 1919 for gasoline sales to exceed those of kerosene.

Although coal-gas was used for most of the 19th century and the first US natural gas pipeline was built in 1891, prior to the 1920s, the vast majority of natural gas produced as a by-product of oil extraction was simply flared away. Superior welding techniques during the interwar years marked a boom in natural gas adoption, but major pipelines were still under construction as late as the 1960’s.

The time-line from Colonel Drake striking pay-dirt in 1859 to mass natural gas adoption took more than a century. Technology and innovation move at a much faster pace today, yet the infrastructural investment needed to transform from carbon to renewable energy will take decades rather than years.

Meanwhile, there remain shorter-term reasons to doubt the arrival of a new commodity super-cycle so precipitously upon the last. Chinese GDP growth has fallen sharply from the double-digit rates of the last decade. Its working age population is shrinking, added to which the People’s Bank of China seem reluctant to allow credit expansion on the scale of previous cycles. Rebalancing towards domestic consumption continues to be official policy.

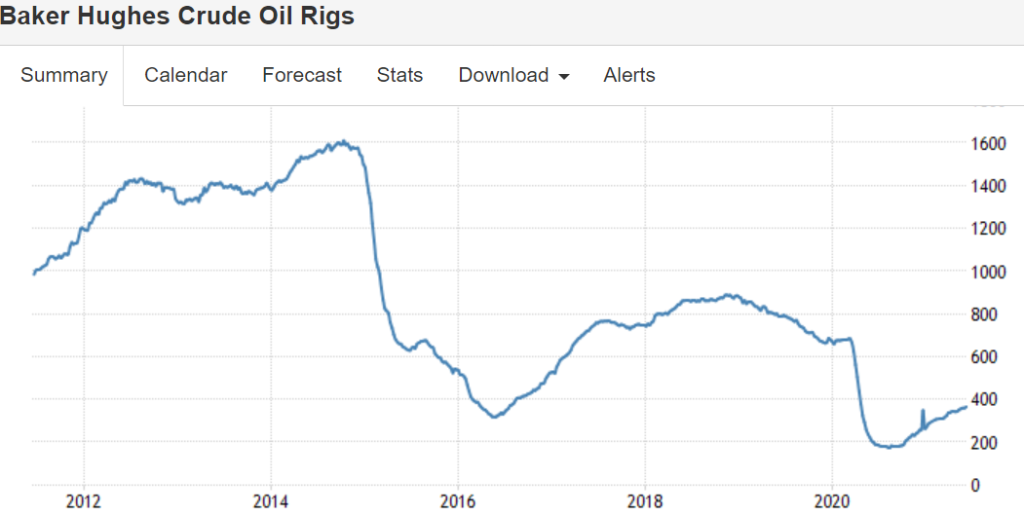

There is near-term evidence of energy supply constraints but over the longer-run oil and gas production, especially from the likes of the US frackers, can raise output rapidly in response to increases in the price of Crude. The chart below shows the fluctuations in the Baker Hughes US Oil Rig count over the past decade, no shortage of capacity is apparent here: –

Source: Baker Hughes, Trading Economics

Agricultural commodities tend to operate on even shorter supply cycles. If supply constraints send Wheat prices higher, farmers respond by switching away from Corn. Seasonal adjustments can be rapid.

The GSCI may have hit its lowest since the 1980’s last April and prices may have doubled since then, but it is still more than 75% below its June 2008 peak. Further upside may be seen as the global economy makes up for a year of lost economic growth, but as economic growth returns to normality demand for energy is likely to moderate just as fresh supply comes on stream.

The spending plans of the US administration may maintain demand in the US but China seems determined to nip its domestic credit bubble in the bud. In broad terms these factors counter-balance one another. According to the Federal Reserve, US GDP is forecast to range between 5% and 7.3% in 2021, falling to 2.5% to 4.4% in 2022 and 1.7% to 2.6% in 2023, meanwhile, according to the OECD, Chinese growth will moderate from 8.5% in 2021 to 5.8% in 2022.

Conclusion and Investment Opportunities

Back in January Goldman Sachs predicted a new commodity super-cycle. They see rising wages leading to faster, commodity price positive, home formation and more synchronised social policies, akin to those of 1960s ‘War on Poverty’ campaign. In other respects they believe this cycle has stronger parallels to the 1970s than the 2000s. Goldman expect industrial capex to run at 2000 levels whilst social rebuilding generates a 1970s style consumer boom.

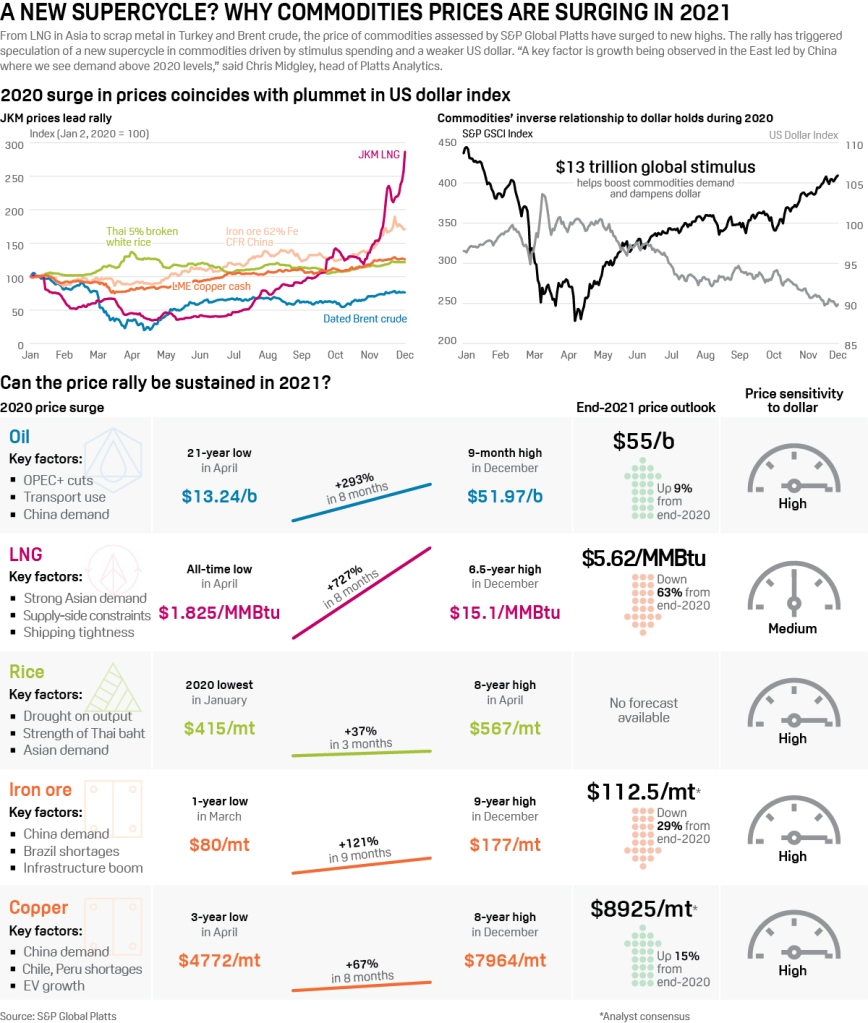

S&P present some of these arguments in a useful infographic: –

Source: S&P Global

US unemployment has fallen from 11.1% to 5.8% during the last 12 months, even in the harder hit Euro Area it has declined from 8.7% to 8%, whilst Chinese data has followed a similar trajectory, falling from 6.1% to 5% since February 2020. Nonetheless, much of the global economy remains in some form of lockdown, with economic activity fuelled by fiscal spending. It remains difficult to envisage the conditions for a near-term sustainable economic boom. Remove global monetary and fiscal relief and commodity demand will evaporate.

As a general rule, in commodity and financial markets, what goes up price must eventually come back down. The price of US Stud Lumber (chart above) is well off its highs. Governments and their central bankers can attempt to remove the punch-bowl, but the markets are unlikely to take it well.

I published this essay at the end of last year but as Cryptocurrencies and Digital Asset gain further prominence, I take the liberty of sharing once more. Central Bank Digital Currencies will be the next ‘innovation’ but we may see money, traditionally a store of value and a means of exchange, become either one or the other.

Digital Currencies and US Dollar Dominance

Macro Letter – No 134 – 27-11-2020

Relax, Rotate, Reflate

November has been an interesting month for financial markets around the world. The US Presidential election came and went and with its passing financial market uncertainty diminished. This change of administration is undeniably important, but its effect was overshadowed by the arrival of three vaccines for Covid-19. As I write (Thursday 26th) the S&P 500 Index is within 30 points of its all-time high, amid a chemical haze of pharmaceutical hope, whilst the VIX Index has tested its lowest level since February (20.8%). The Nasdaq Composite is also near to its peak and the Russell 2000 Index (an index of smaller capitalisation stocks) burst through its highs from February 2020 taking out its previous record set in September 2018. The chart below shows the one year performance of the Russell 2000 versus the S&P500 Index: –

Source: Yahoo Finance, S&P, Russell

It is worth remembering that over the very long term Small Caps have outperformed Large Caps, however, during the last decade the rapid growth of index tracking investments such as ETFs has undermined this dynamic, investment flows are a powerful force. I wrote about this topic in June in – A Brave New World for Value Investing – in which I concluded: –

Stock and corporate bond markets have regained much of their composure since late March. Central banks and governments have acted to ameliorate the effects of the global economic slowdown. As the dust begins to settle, the financial markets will adjust to a new environment, one in which value-based stock and bond market analysis will provide an essential aid to navigation.

The geopolitics of trade policy, already a source of tension before the pandemic struck, has been turbo-charged by the simultaneous supply and demand shocks and their impact on global supply chains. Supply chains will shorten and diversify. Robustness rather than efficiency will be the watch-word in the months and years ahead. This sea-change in the functioning of the world economy will not be without cost. It will appear in increased prices or reduced corporate profits. Value-based investment analysis will be the best guide in this brave new world.

To date, evidence of a return to Value Investing seems premature, Growth still dominates and the structural acceleration of technology trends seems set to continue – one might say, ‘there is Value in that.’

The vaccine news led to a rotation out of technology stocks but this was more to do with profit taking, new ‘Tech’ buyers quickly emerged. The rotation into Small Caps was also echoed among a number of out of favour sectors such as Airlines and Energy. It was enough to prompt the creation of a new acronym – BEACHs – Booking, Entertainment, Airlines, Cruises and Hotels.

Source: Barchart.com, S&P

Above is the one year performance of the 11 S&P 500 industry sectors. Information Technology remains the leader (+38%) with Energy bringing up the rear (-32%) however the level of dispersion of returns is unusually which has presented an abundance of trading opportunities. The table below shows the one, three and six month performance for an expanded selection of these sectors: –

Source: Tradingview

Beyond the US, news of the vaccines encouraged both European and emerging markets, but the latter (EEM), helped by the strong performance of Chinese stocks, have tracked the US quite closely throughout the year, it is Europe (IEUR) which has staged the stronger recovery of late, although it has yet to retest its February highs: –

Source: Yahoo Finance, S&P, MSCI

In the aftermath of the US election, US bond yields have inched higher. From an all-time low of 32bp in March, 10yr yields tripled, testing 97bp in the wake of the Democrat win. Putting this in perspective, the pre-Covid low was seen at 1.32% in July 2016. The current concern is partly about the ‘socialist’ credentials of President-elect, Biden, but the vaccine announcement, together with the prospect of a return to some semblance of normality, has also raised the spectre of a less accommodative stance from the Fed. There was initial fear they might ‘take away the punch-bowl’ before the global economy gets back on its knees, let alone its feet. Governor Powell, quickly dispelled bond market fears and yields have since stabilised.

Longer-term, these bond market concerns may be justified, as this infographic from the McKinsey Institute reveals, combined central bank and government fiscal stimulus in 2020 has utterly eclipsed the largesse witnessed in the wake of the 2008 crisis: –

Source: McKinsey

Bond watchers can probably rest easy, however, should the global economy stage the much vaunted ‘V’ shaped recovery economists predicted back in the spring, only a fraction of the fiscal stimulus will actually materialise. Nonetheless, prospects for mass-vaccination, even in developed countries, remains some months away, both monetary and fiscal spigots will continue to spew for the present.

On the topic of monetary policy it is worth noting that the Federal Reserve previously employed ‘yield curve control,’ though it was not called by that name, back in April 1942, five months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Under this arrangement the Fed committed to peg T-Bills at 3/8th and implicitly cap long-dated T-Bonds at 2.5%. The aim was to stabilize the securities market and allow the government to engage in cheaper debt financing during the course of WWII. This arrangement only ended with the Treasury – Fed Accord of 1951 in response to a sharp peace-time resurgence in inflation. This chart shows the period from 1941 (when the US entered WWII) up to the middle of the Korean War: –

Source: US BLS

I believe we will need to see several years of above target inflation before the Fed to feel confident in raising rates aggressively. The experience of Japan, where deflation has been lurking in the wings for decades, will inform Fed decision making for the foreseeable future.

Returning to the present environment; away from the stock and bond markets, oil prices also basked in the reflected light shining from the end of the pandemic tunnel. West Texas Intermediate, which tested $33.64/bbl on 2nd, reached $46.26/bbl on 25th. The energy sector remains cautious, nonetheless, even the recent resurgence leaves oil prices more than $15/bbl lower than they were at the start of the year.

Looking ahead, the stock market may take a breather over the next few weeks. A vaccine is coming, but not immediately. US politics also remains in the spotlight, the Republicans currently hold 50 Senate seats to the Democrats 48. If Democrats secure the two seats in Georgia, in the runoff election on 5th January, VP Elect, Harris, will be able to use her ‘tie-break’ vote to carry motions, lending the Biden Presidency teeth and hastening the expansion of US fiscal policy.

The stock market has yet to make up its mind about whether Biden’s ‘New New Dealers’ are a positive or a negative. Unemployment and under-employment numbers remain elevated as a result of the pandemic: and, whilst bankruptcies are lower than at this time last year, the ending of the myriad schemes to prolong the existence of businesses will inevitably see those numbers rise sharply. Does the stock market benefit more from the fiscal spigot than the tax increase? This is a question which will be mulled, chewed and worried until long after Biden’s inauguration on January 20th.

Meanwhile the trend accelerations in technology which I discussed in – The prospects for Emerging and Frontier Markets in the post-Covid environment – earlier this month, continue. The chart below shows how information industries have been transforming the makeup of global trade ever since the great financial crisis: –

Source: ECIPE, OECD, TiVA, van der Marel

Manufacturing trade is in retreat, trade in digital services is accelerating. The chart above stops at 2015, when we have the data to incorporate the period of the current pandemic, I expect the pace of growth in information industries to have gain even greater momentum.

Back in 1987, MIT economist and Nobel Laureate, Robert Solow, observed that the computer age was everywhere except for the productivity statistics. During the 1990’s technology productivity growth was finally observed, but the past decade has seen a string of disappointing productivity growth statistics, yet they have coincided with digitisation transforming vast swathes of the global economy, perhaps the next decade will see the fruit of these labours. I believe we can look forward to significant productivity improvements in the coming years. Stock prices, however, are forward looking, their valuations may seem extended but this may be entirely justified if technology ushers in a new golden age.

TRANSFIN. Podcasts: Banter On All Things Worthy

Macro Letter No 132 – 04-09-2020

Step-change at the Fed – Reaching for the stars

In a speech entitled – New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review – given on August 27th, at the Jackson Hole, Kansas City Federal Reserve Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell, announced a change in the emphasis of the dual mandate. The new focus is on promoting full-employment even at the expense of price stability.

The policy review was, of course, more nuanced. Past policy decisions were analysed and found wanting – especially the rate increases witnessed between 2015 and 2018. The extraordinary flatness of the Phillips Curve was noted; the lower trend rate of economic growth, contemplated; the stickiness of inflation expectations, contextualised: and the ever rising, pre-pandemic participation rate, considered. What the speech omitted was any discussion of forward guidance or expectations of the change in size, composition or direction of the Fed’s, already historically large, balance sheet.

For financial markets the key change is contained in this paragraph: –

Our statement emphasizes that our actions to achieve both sides of our dual mandate will be most effective if longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent. However, if inflation runs below 2 percent following economic downturns but never moves above 2 percent even when the economy is strong, then, over time, inflation will average less than 2 percent. Households and businesses will come to expect this result, meaning that inflation expectations would tend to move below our inflation goal and pull realized inflation down. To prevent this outcome and the adverse dynamics that could ensue, our new statement indicates that we will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time. Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

The initial market response saw stocks rally whilst 10yr T-bond yields rose – testing 0.79%. During the week which followed, 10yr yields slipped back to 0.62%. Equity markets subsequently switched focus and moved on, returning to their obsession with the ever rising tide of technology stock earnings expectations. Even the Dow Jones Industrials Average Index has been effected by the tech boom, as reported by S&P – Dow Jones Industrial Average: 124 Years and It Keeps Changing – the index changes, announced on August 31st included, Salesforce.com (CRM) replacing Exxon Mobil (XOM), Amgen (AMGN) replacing Pfizer (PFE), and a tech switch with Honeywell International (HON) replacing Raytheon Technologies (RTX).

Returning to monetary policy, the Fed announcement was hardly a surprise, the August 10th, FRBSF Economic Letter – Average-Inflation Targeting and the Effective Lower Bound had already set the tone. The chart below reveals the Fed’s inflation targeting dilemma: –

Source: FRBSF

If the average for Total PCE over the last decade has been less than 1.5%, allowing it to rise above 3% for a few years is just what is needed for the Fed to get back on track.

Setting aside the vexed questions of whether an Inflation Target is appropriate or, deflation, a good or bad phenomenon, we need to investigate the structural cause of the decline in inflation. Here I will resort to the monetary equation of exchange: –

MV = PQ

Where: –

M is the total nominal amount of money supply in circulation on average in an economy.

V is the velocity of money, or the average frequency with which a unit of money is spent.

P is the price level.

Q is an index of real expenditures for newly produced goods and services.

The basic problem for the Fed is that, despite their success in expanding money supply (see below): –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

The velocity of circulation has continued to plummet: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

I discussed the rapid expansion of money supply in more detail in a June article for AIER – Global Money Supply Growth and the Great Inflation Getaway: –

I suspect, fearful of repeating the mistakes made by the Bank of Japan, that once the inflation genie is finally out of the bottle, central bankers will forsake the hard-learned lessons of the 1970’s and 1980’s and allow inflation to conjure away the fiscal deficits of their governments at the expense of pensioners and other long-term investors.

Of course, consumer price inflation may not return, even with such egregious debasement as we have seen thus far, as Michel Santi suggests in Japan: a sleeping beauty: –

A global battle has thus been raging on pretty much since the deflationary episodes of the 2010s in an attempt to relaunch economies by dint of inflation. In this respect, the Japanese experiment, or rather multiple experiments, remains a case study to show that inflation is still proving a difficult spectre to revive.

Santi, points to demographic decline, a trend in which Japan is a world leader, together with, what he considers to be, an irrational fear of debt and deficits, which renders people unwilling to spend. In this scenario, government, corporate and consumer debt cannot be inflated away and sits like a giant toad atop all the animal spirits that might reignite economic growth. He also alludes to the profound changes in the nature of work – from permanent to temporary, from employed to self-employed, from office based to remote. These changes have rendered the Phillips Curve redundant.

The dual mandate of full employment and price stability has never been so easy for the Federal Reserve to achieve. That, at least, was the case until the global pandemic unknit the fabric of the global market economy. Now, the Federal Reserve – and central bankers in general – are faced with the prospect that printed money, whether it be sterilised or not, will either be invested or hoarded. In this scenario, the greater the debt the less likely prices are to rise as a result of demand-pull inflation. On the opposite side of the inflation equation, the shortening of global supply chains and the need for dual-redundancy, agin another unwelcome and unexpected lockdown, has created the classic bottlenecks which lead to product scarcity, personified in cost-push inflation.

Interest Rates, Global Value Chains and Bank Reserve Requirements– published in June of last year, notes that Global Value Chains have suffered and shortened since 2009; that, despite low interest rates, financing costs remain too high and yet, at the same time, bank profitability has not recovered from the damage caused by the great financial recession. Nonetheless, those same banks, which were supposed to have been broken up or dramatically deleveraged, remain still too big to fail. My conclusion looks dismally prescient: –

The logical solution to the problem of the collapse of global value chains is to create an environment in which the credit cycle fluctuates less violently. A gradual normalisation of interest rates is the first step towards redemption. This could be accompanied by the removal of the moral hazard of central bank and government intervention. The reality? The societal pain of such a gargantuan adjustment would be protracted. It would be political suicide for any democratically elected government to commit to such a meaningful rebalancing. The alternative? More of the same. Come the next crisis central banks will intervene, if they fail to avert disaster, governments’ will resort to the fiscal spigot.

US interest rates will converge towards those of Europe and Japan. Higher stock/earnings multiples will be sustainable, leverage will increase, share buy-backs will continue: and the trend rate of economic growth will decline. Economics maybe the dismal science, but this gloomy economic prognosis will be quite marvellous for assets.

Conclusion and Investment Opportunities

According to data from S&P, US share buybacks were lower for the second quarter in a row in Q2, 2020. They amounted to $166bln, versus $205bln in Q1 and $190bln in Q2, 2019 – this is still the seventh highest quarterly amount ever recorded. The chart below shows the evolution of buybacks over the last two decades: –

Source: S&P, FT

The consolidation of the US equity market continues – from a high of 7,562 on July 31, 1998, the Wilshire 5000 Index list of constituents has shrunk to just 3,473 names. This is a side effect of the fact that debt finance remains cheaper than equity finance. According to a recent article published by the Financial Times – US corporate bond issuance hits $1.919tn in 2020, beating full-year record corporate issuers have raised more capital in the first eight months of 2020 than in any previous full year. Low rates going to no rates, thanks to the actions of the Fed, is said to have driven this step-change in activity. The reticence of commercial banks to extend finance, despite the favourable interest rate and liquidity environment, is a contributing factor: –

Source: Refinitiv, FT

The Covid pandemic has accelerated many of the economic and financial market trends which have been in train since the end of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Lower interest rates, more quantitative easing, further share buy-backs and greater debt issuance – by borrowers’ individual, corporate and national – look set to continue.

A global economic depression is looming, yet the price of many assets continues to rise. In a similar manner to the Tech bubble of the late 1990’s, today’s valuations rely more on the willing suspension of disbelief than on any sober assessment of earnings potential. The US stock market has outperformed partly due to the high proportion of technology stocks, as the chart below (from May) shows: –

Source: FactSet, Goldman Sachs

The magnitude of this fiscal and monetary response has already reached far beyond the United States. The table below shows those national stock markets with a positive year to date performance exceeding 5%: –

Source: Trading Economics, Local Stock Exchanges

I have deliberately excluded the Nasdaq 100 which is currently up more than 57%. Other countries will catch up. The US$ has weakened, since February, on a trade weighted basis: –

Source: BIS, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

In a competitive race to the bottom, other central banks (and their governments) will expand monetary (and fiscal) policy to stop their currencies appreciating too fast.

Global bond yield convergence will continue, stock market strength will endure. Inflation will creep into consumer prices gradually and the central banks will turn a blind eye until it is too late. The world economy may be on its knees but, in general, asset prices will continue to reach for the stars.

Macro Letter – No 131 – 21-08-2020

When does a recession become a depression?

There is a tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.

William Shakespeare (Julius Caesar)

When your neighbour loses their job, it’s a recession.

When you lose your job, that’s a depression!

Harry S. Truman (33rd President of the Unites States)

The common knowledge definition above is grim and highly specific, but its banality serves to highlight the fact that the recession/depression question is not that simple to answer. Back in 2007 The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco – What is the difference between a recession and a depression? – attempted to reach a conclusion. They embraced the NBER definition of a recession: –

A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. A recession begins just after the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends as the economy reaches its trough. Between trough and peak, the economy is in an expansion. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief and they have been rare in recent decades.

And turned to Gregory Mankiw to distinguish between the two states of economic contraction: –

There are repeated periods during which real GDP falls, the most dramatic instance being the early 1930s. Such periods are called recessions if they are mild and depressions if they are more severe.

Despite the Federal Reserve’s valiant efforts, the simpler and more commonly accepted definition of a recession is a consecutive two quarters of decline in GDP. When it comes to depressions, however, there is little consensus; the two most common descriptions are: –

Whilst the two definitions are not mutually exclusive, they are broadly different. I believe the difference between a recession and a depression is more nuanced. A recession is a natural part of the business (or perhaps we should say credit) cycle, a depression, by contrast, involves the physical destruction of the economy – businesses are irreparably broken, employment opportunities terminally destroyed, investment has to be totally written off.

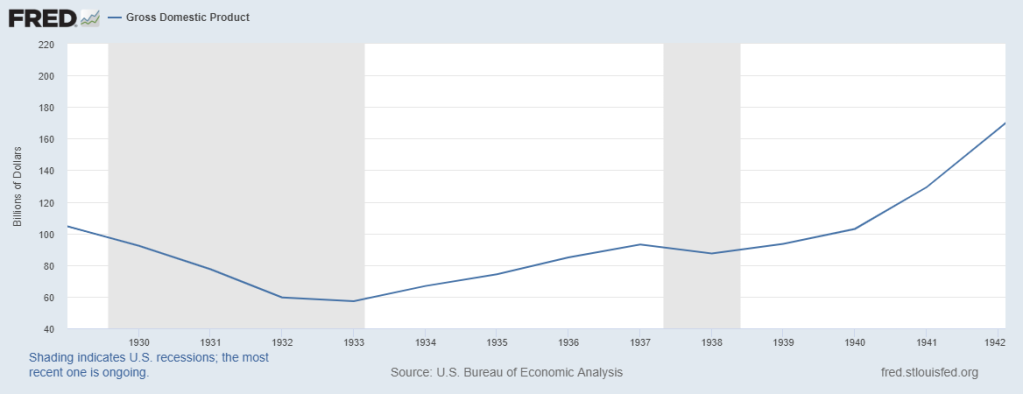

An alternative approach is to examine previous great depressions. Alas, this method proves equally inconsistent, for example the Great Depression of the 1930’s is generally considered to have lasted from 1929 to 1941 and yet, as the chart below reveals, there were only two distinct periods of declining GDP growth between 1930 and 1933 and again between 1937 and 1938: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Notwithstanding my more prosaic definition above, I favour the two year plus definition over that of a sharp decline in GDP. A recession hurts some parts of an economy, a depression is more widespread.

Another factor often associated with recessions and depressions is a rise in the rate of unemployment. Historically, rising unemployment has preceded the onset of recessions and only once recessions have become protracted have they been dubbed depressions.

A further differentiator relates to the absolute level of inflation. In general, as inflation rises, central banks respond by raising short-term interest rates. This helps to cool overheating economies, however, if they tighten too aggressively they may prompt a recession as the credit cycle is forced into a sharp contraction. By contrast a depression is often accompanied by an absolute fall in the price level, caused by an excessive overhang of domestic or corporate debt.

As an investor, why does a depression definition matter? Because financial markets are forward looking. If investors believe the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic will be ‘V’ Shaped, then, even a 20% decline in GDP, together with zero interest rates, price support for government bonds and a fiscal expansion on a scale not witnessed since the ‘New Deal’ of FDR, will rapidly translate inot a sharply rising stock market. If, by contrast, it becomes clear that a tsunami of creative destruction is sweeping away entire industries, then even the most lavish of New New Deals may be insufficient to hold back the tide of stock liquidation as market participates rush to the safety of cash.

So far the official policy response has been sufficient to convince investors that a depression will be avoided. Scratch the surface of the S&P 500, however, and a rather different picture appears. The chart below shows market performance up to the end of May. The same five technology stocks have continued to drive S&P 500 index performance since then: –

Source: FactSet, Goldman Sachs

Technology has been the top performing sector. One argument for such elevated valuations rests on the premise that the pandemic has accelerated a wide range of technology trends bringing with it the potential for much swifter profits. In finance parlance, the net present value of future technology cash-flows has been brought forward by, some analysts suggest, several years. No wonder, they argue, that these stocks have broken to new all-time highs: and will continue, higher.

Since May, the broader stock market has hung of tech coattails (at the time of writing – 19-8-2020 -the MSCI World Index is up 1.73% YTD). For the present, hope triumphs over fear, yet vaccines remain many months from being widely available, meanwhile, for the Northern hemisphere, autumn – and fears of a second wave of infections – draws imminently near.

For emerging markets the situation is worse still. As Carmen and Vincent Reinhart, writing in Foreign Affairs – The Pandemic Depression– put it: –

Although dubbed a “global financial crisis,” the downturn that began in 2008 was largely a banking crisis in 11 advanced economies. Supported by double-digit growth in China, high commodity prices, and lean balance sheets, emerging markets proved quite resilient to the turmoil of the last global crisis. The current economic slowdown is different. The shared nature of this shock—the novel coronavirus does not respect national borders—has put a larger proportion of the global community in recession than at any other time since the Great Depression. As a result, the recovery will not be as robust or rapid as the downturn. And ultimately, the fiscal and monetary policies used to combat the contraction will mitigate, rather than eliminate, the economic losses, leaving an extended stretch of time before the global economy claws back to where it was at the start of 2020.

The World Bank estimates globally more than 60mln people will be pushed into severe poverty. Meanwhile, in developed countries, bankruptcies, which have been postponed by government intervention, may meet their personal epiphanies as fiscal largesse is suddenly withdrawn. Unless the lockdown restrictions are lifted and people feel safe, both medically and financially, to venture out and spend, the destruction of large swathes of developed market economies has simply been deferred.

By next month we will have experienced two quarters of diminished growth – this is a deep recession already. Swathes of the economy have been permanently altered, making a depression highly likely. Millions of workers have been displaced, it will take more than a handful of months for them to be retrained. Without the consumption demand from these erstwhile workers, it will be difficult for new and existing companies to create the growth they need to hire new employees.

Fiscal spending will need to be undertaken on a much larger scale, and for much longer, than has been envisaged so far. In all the major financial crises since 1850, the average time for per capita GDP to recover to the pre-crisis level was eight years. To date it is estimated that the G20 response to the pandemic has amounted to $11trln. Most of these measures have been ‘temporary’ or ‘short-term.’ It is quickly becoming clear, the disruption to employment, business and sectors of the economy will be protracted and, in many cases, permanent, The IMF estimate that for advanced economies the deficit-to-GDP ratio will rise from 3.3% in 2019 to 16.6% this year. For emerging economies, where the capacity for fiscal expansion is more limited, the ratio is expected to swell from 4.9% last year to 10.6% in 2020. Whilst for advanced economies the cost of borrowing has remained low in emerging markets financing costs have risen. The burden of fiscal stimulus will inevitably fall most heavily upon the treasuries of the advanced economies.

Conclusion

As Sir Winston Churchill once said: –

Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

In the aging societies of the West (and elsewhere) the individual need for income remains key. Developed nation governments are fortunate in their ability to borrow more cheaply than at any time in economic history. Whilst it is at odds with my Austrian, free-market instincts, I am forced to admit that fiscal policy is the least panful weapon available to combat the economic catharsis created by the pandemic. Economically, there will be a heavy price to pay, but the alternative is a dangerous cocktail of political fragmentation and polarisation.

For investors the task of securing steady real income remains challenging. Private debt and asset backed lending, which offers high yield, comes with both default and liquidity risk. The chart below looks at some of the public market options, financial repression is rife across the credit spectrum: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

High income stocks might be an alternative but they offer no guarantee, no matter how ‘blue-chip’ the name. An addition to the acceleration in technology trends, growth stocks in general are benefitting from the exceptionally low interest environment, but there will be a greater number of failures because the cost of speculative finance is also at an historical low. Active management has been unfashionable for at least a decade but looking ahead preservation of capital is going to be more important than capturing out-sized gains.

I wrote about value investing back in June in – A Brave New World for Value Investing – concluding that: –

Stock and corporate bond markets have regained much of their composure since late March. Central banks and governments have acted to ameliorate the effects of the global economic slowdown. As the dust begins to settle, the financial markets will adjust to a new environment, one in which value-based stock and bond market analysis will provide an essential aid to navigation.

The geopolitics of trade policy, already a source of tension before the pandemic struck, has been turbo-charged by the simultaneous supply and demand shocks and their impact on global supply chains. Supply chains will shorten and diversify. Robustness rather than efficiency will be the watch-word in the months and years ahead. This sea-change in the functioning of the world economy will not be without cost. It will appear in increased prices or reduced corporate profits. Value-based investment analysis will be the best guide in this brave new world.

I would add an additional strategy to the investment armoury, a momentum overlay. With fiscal and monetary policy continuing to support economies as they transition to the new world order, capital flows will be a powerful arbiter of investment return. Technology stocks may look expensive by most normal metrics but the trend is patently clear. Do not emulate Cnut The Great, but do as Brutus advises in the opening quote, after all, financial market liquidity flows like tide.

Macro Letter – No 130 – 26-06-2020

After the flood – Beyond fiscal and monetary intervention

In my last Macro Letter – A Brave New World for Value Investing – I anticipated the beginning of a new phase for equity investment. In this Letter I look at the existing business and economic trends which have been accelerated by the pandemic, together with the new trends ignited by this sea-change in human behaviour.

In economic terms, the Covid pandemic began with a supply-shock in China as they were forced to lockdown the Wuhan region. This exacerbated strains which had already become evident in trade negotiations between China and the US, but also revealed weaknesses in the global supply chains. A kind of ‘Mexican Wave’ has followed, with a variant on the initial supply-shock occurring in successive countries as the virus spreads from region to region and governments responded with lockdowns.

The supply-shock has gone hand in hand with a global demand-shock. The key difference between this recession and previous crises is the degree to which it has impacted the service sector. According to 2017 data, the service sector represents 65% of global GDP, whilst Industrial/Manufacturing accounts for 25%, Agriculture represents only 3.43%. Over time, Agriculture and Manufacturing has become more increasingly automated, the principle growth sector for employment is Services. The ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Fourth edition states: –

As at 17 May 2020, 20 per cent of the world’s workers lived in countries with required workplace closures for all but essential workers. An additional 69 per cent lived in countries with required workplace closures for some sectors or categories of workers, and a further 5 per cent lived in countries with recommended workplace closures.

The latest ILO estimate for Q2, 2020 indicates a 10.7% decline in working hours – equivalent to 305mln lost jobs worldwide. 60% of these job losses have been in four industries, leisure, retail, education and, perhaps counter-intuitively, healthcare. The knock-on effects have been felt almost everywhere.

Governments and central banks have responded. The chart below shows the rapid expansion in central bank balance sheets: –

Source: Yardeni, Haver Analytics

The Federal Reserve began their latest round of quantitative easing in August 2019, well before the onset of the pandemic. They have added $3.3tlrn in nine months, seeing their balance sheet balloon to $7.1trln.

Around the world, governments have also reacted with vigour; on May 20th the IMF updated their estimate of the global fiscal response to $9trln, of which $8trln has emanated from G20 countries. The geographic breakdown as a percentage of GDP can be seen in the table below: –

Source: IMF

The majority of global stimulus has come from the richer developed nations. Assuming this pattern continues, emerging market equities are likely to lag. The table below ranks a selection of emerging economies by four measures of financial strength, public debt, foreign debt, cost of borrowing and reserve cover: –

Source: The Economist, IMF, JP Morgan, iShares

Overall, whilst the flood may subside, global expenditure should continue to rise as the pandemic sweeps on across the globe. Whilst loan forbearance and forgiveness, together with state guarantees, will help to maintain the solvency of many existing corporations, new spending will be aimed at stimulating employment. Infrastructure projects will be legion.

Impact on Industry Sectors

For investors, the abrupt changes in supply and demand, combined with the impact of the fiscal and monetary response, make navigating today’s stock markets especially challenging. To begin, here is a chart from 2019 showing a breakdown of industry sectors in the US by their contribution to GDP: –

Source: Deloitte, BEA, Haver Analytics

This tells us that finance, insurance and real estate are the largest sector but it fails to tell us which sectors are thriving and which are not: –

Source: Deloitte, BEA, Haver Analytics

Here we see the continued march of digital transformation, but also the ever increasing share of healthcare services in GDP; near to four decades of asset price appreciation has created an asset rich aging cohort in developed economies which, if not healthier then definitely wealthier. Looking ahead, developed nations are better equipped to weather the crisis better than their developing nation peers. Within developed nations, however, smaller businesses, especially those which cannot access capital markets, will fail, whilst larger firms will fare far better. Private Equity funds will also find rich pickings among the plethora of distressed private market opportunities.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, several trends have accelerated, others have been truncated or reversed. Social behaviour has had a negative impact on travel, leisure and retail. Declining demand for travel has damaged a range of industries including airlines, autos, oil and gas. The leisure sector has been hit even harder with hotels, restaurants and bars closed, in many cases forever. The sports industry has been severely undermined. Meanwhile the decline in retail has accelerated into a downward spiral.

Nonetheless, several industries have benefitted. Within retail, online sales have hit new records, grocery sales have ballooned. Healthcare has gone digital, from consulting to dispensing productivity gains have been evident. The home improvements industry has benefitted even as commercial real estate has suffered. Working from home will be a permanent feature for many office workers. Every existing home owner will need to create a permanent office space, every new home buyer will need more space to incorporate an office. Longer, occasional, commutes will lead people to move further from the city. Some workers will move to more clement climes, requiring less energy. Structural changes in where we live and how we live present threats and opportunities in equal measure. For example, every house will require better communications infrastructure, high speed connectivity and broad, broadband will become the norm.

Changes in the delivery of goods (direct to homes rather than to retail outlets) means more inventory will held in out-of-town locations. Inner city retail and commercial property businesses will consolidate as out-of-town commercial thrives. New out-of-town property demand will also emerge from the manufacturing sector. The on-shoring of production was already in train, with robots replacing cheap labour from developing countries, now, concern about the robustness of supply chains, especially for critical manufactures such as pharmaceuticals, will encourage a wave of old industries in developing countries to be reborn. Whereas in retail, larger inventory may become more prevalent, in manufacturing, ‘just-in-time’ delivery and lower transportation costs will compensate for higher fixed production costs.

The energy sector has suffered a medium-term setback, for example, 28% of all US gasoline is consumed in the daily commute. After the lockdown, some commuters will choose to travel alone rather than by public transport, many more will now work permanently from home. Yet whilst gasoline demand falls, demand for diesel, to fuel the home delivery revolution, will rise. Home heating (and cooling) is also set to rise and, with it, demand for heating oil and natural gas. Overall demand may be lower but there will be many investment opportunities.

In healthcare, aside from tele-medicine, which is forecast to capture between one third and half of consultation demand, there is also increased appetite for bio-sensors to measure multiple aspects of health. Hospital consolidation will continue in an attempt to drive efficiency. On-shoring of drug manufacture may well be mandated, online delivery is likely to become the new normal, especially to the elderly and infirm who are advised to shelter-in-place. On-shoring creates domestic jobs, government favour will focus on these companies.

Airlines will be forced to diversify or merge; I envisage a mixture of both strategies. A diversification into car hire, travel insurance and hotels seems likely. Many airlines are national carriers, they possess an implicit government guarantee, their financing costs will remain lower, their low-budget competitors will diminish, fare discounts will become fewer and, thereby, their fortunes may conceivably rebound.

The automobile industry remains in a state of turmoil, but new technology will continue to determine its fortune. If de-urbanisation continues, whilst commuting will decline, there will be an increased demand for individual car ownership, especially electric vehicles. In the fullness of time, the industry will transform again with the adoption of driverless transportation.

Technology will, of course, be ubiquitous. The fortunes of the cybersecurity sector have been ascendant since the crisis began, but even relatively ‘non-tech’ businesses will benefit. Commercial real estate will gain as tech firms seek out ever larger data centres to support their cloud computing needs. The auto industry will benefit from improvements in battery storage and charging times. This will also change the economics of electricity for homes and factories. Green energy will come of age.

Tourism will recover, the human race has not lost the desire to travel. In Europe tourism is down between 30% and 40% – it accounts for 10% of GDP. The rebound will be gradual but the travellers will return. More consumers will buy on-line.

Banking and finance will evolve to meet the challenges and needs of the industrial and services sector. Certain trends will continue, bricks and mortar will give way to on-line solutions, branch networks will consolidate. With government support, or threat, existing loans will be extended, new loans made. As household savings rise, new credit will be granted to new and existing entities, few questions will be asked.

Insurance companies will consolidate, once claims are paid, premiums will rise and competition lessened. As with banking more consumers will move on-line.

Employment

Looking beyond the business potential of different industry sectors and the technological advances which will support them, we should remember that governments around the globe will direct fiscal policy to alleviate unemployment, the initial flood of fiscal aid may moderate but if the tide goes out the ebb will be gradual, this is one of the benefits of a fiat currency system. According to the ILO, in 2019, employment in services accounted for 50%, Industry 23% and Agriculture 27%. The chart below shows how employment by sector has evolved over the last 28 years: –

Source: World Bank, ILO

The services sector has embraced employees leaving agriculture, whilst industry has grown without significant employment growth. The leisure industry, including hotels, restaurants and bars, is one of the largest employers of low-skilled, part-time employment. Consolidation within the hotels sector is inevitable. Larger, better capitalised groups will benefit as smaller enterprises fail. Corporations from beyond the leisure sector will diversify and private equity will fill the gaps which public companies step aside.

Conclusions and Investment Opportunities

In my previous Macro Letter I concluded that value-based analysis would be the best approach to equity investment. On closer examination, one can find risk and opportunity in almost every industry sector. In the last three month, stock markets have risen, but stock return dispersion remains heightened. A prudent, value-oriented, framework should yield the best results in the next few years.

The Giant Debt-for-Equity Swap

I wrote this article in December 2019. Much has changed but with bond yields heading lower on the back of more QE, it still seems surprisingly valid.