During the last three months inflation has become a much debated topic. This article, which was published in March, may still add something to the increasingly heated debate: –

Inflationary Inflection Point or Temporary Blip?

Macro Letter – No 138 – 21-05-2021

First In, First Out – China as a Leading Indicator

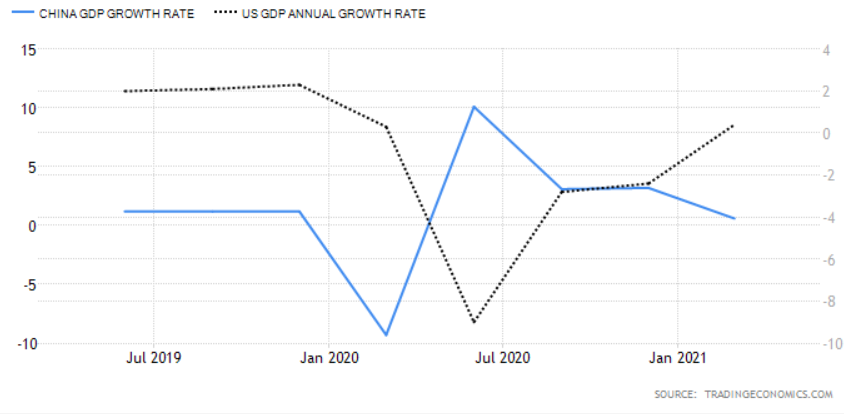

Whilst there are many aspects of the Chinese command economy which differ radically from that of the US, it is worth examining the performance of China’s economy, fiscal and monetary policy, and its financial markets. They may afford some insight into the future direction of other developed and developing markets as we gradually emerge from the Covid crisis: –

Source: Trading Economics

As can be seen from the chart above, whilst China was the first country to be struck by the Covid-19 pandemic it was also the first country to recover, however, a comparison of the Chinese and US bond markets provides a rather different picture: –

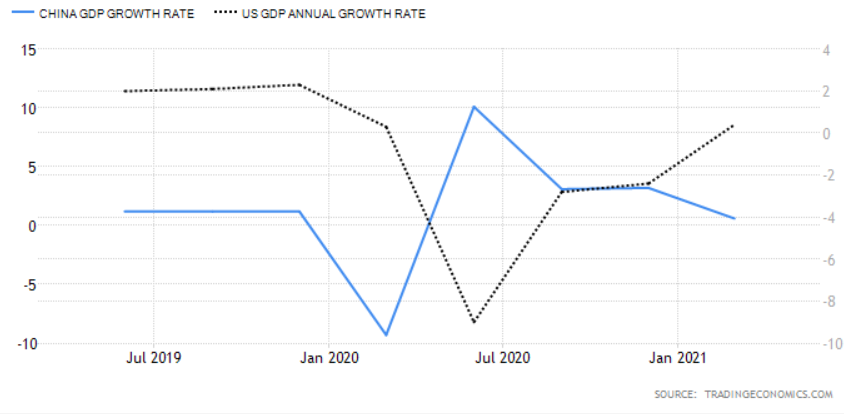

Source: Trading Economics

Chinese bond yields reached their lows at roughly the same time as those of the US, since when they have returned more rapidly to their pre-pandemic levels. If the US follows a similar trajectory the yield on US Treasuries is set to rise further.

It can be argued, however, that the plight of the Chinese bond market is a function of the monetary stance of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). When the crisis first erupted the PBoC cut its interest rate corridor by 0.3% and also drove down Chinese interbank rates by around 1.2% through its open market operations. By May 2020 that policy had changed, accommodation was replaced by a steady drain of liquidity.

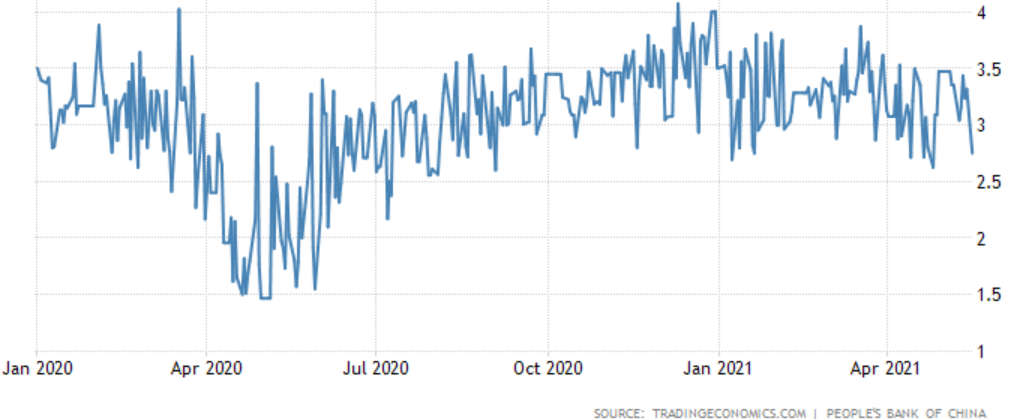

The chart below shows the, rather volatile, 3 month Shibor rate, this is in marked contrast to the ‘lower for longer’ approach taken after the 2008 crisis. The Covid accommodation has been remarkably short-lived: –

Source: Trading Economics, PBoC

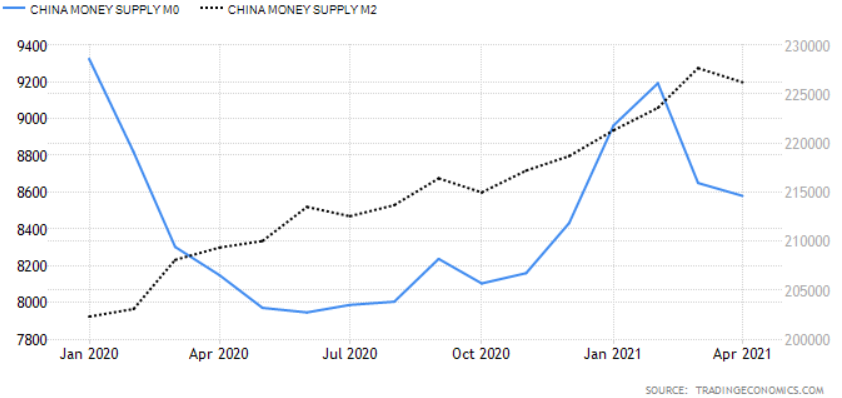

This PBoC tightening, which began in May 2020 and has been accompanied by official talk of the need for stability and the desire to avoid creating asset bubbles, is finally becoming evident in the money supply data: –

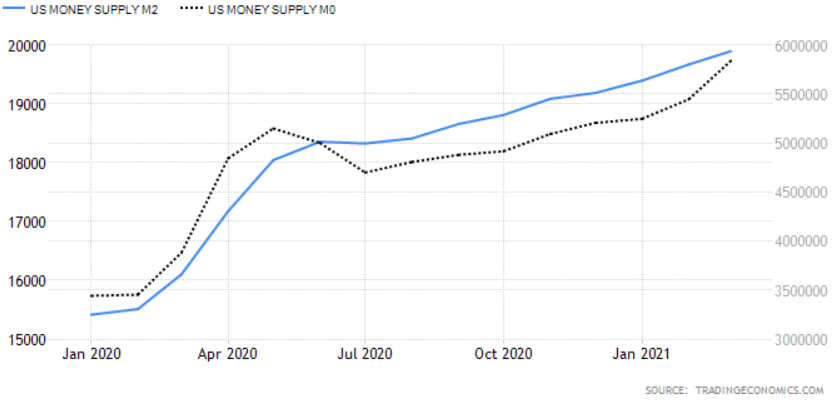

Source: Trading Economics

This contrasts with the continued expansion of US monetary aggregates: –

Source: Trading Economics

One of the challenges facing all central bankers is that interest rates are a blunt tool. Not all China’s asset markets have heeded the PBoC advice. The residential property market, for example, remains red hot despite the introduction of the three red lines policy – which aims to limit their liability-to-asset ratio (excluding advance receipts) to less than 70%, or their net gearing ratio to less than 100%, or their cash-to-short-term debt ratio to less than 1x, or a combination of all three. New home prices surged on regardless, gaining 4.8% in April, led by luxury real estate in Shenzhen, Shanghai and Guangzhou which is up 16% to 19% over the last year – a further tightening of regulation seems inevitable.

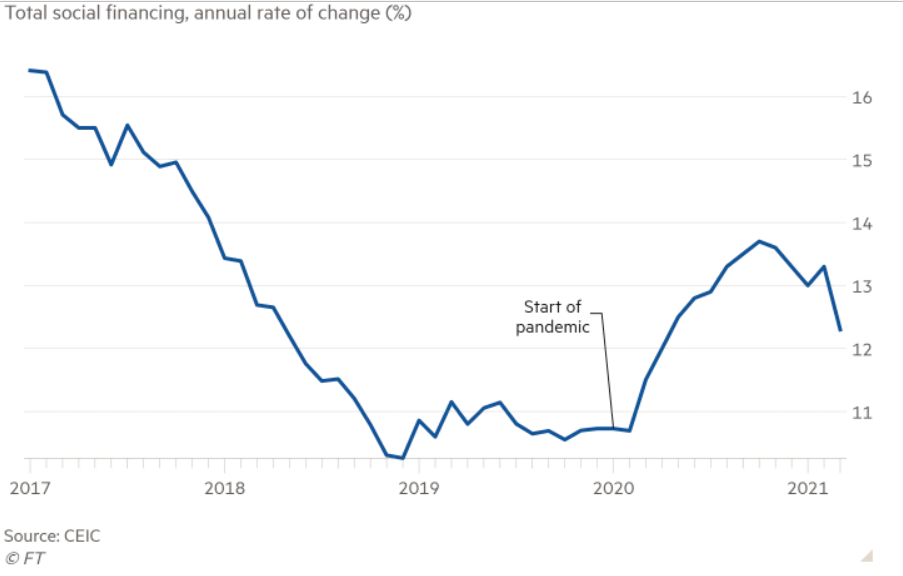

The PBoC has had greater influence elsewhere, Total Social Financing, their favoured measure of lending across the entire domestic financial system, rose by 12% in March, its slowest pace since April 2020:-

Source: Financial Times, CEIC

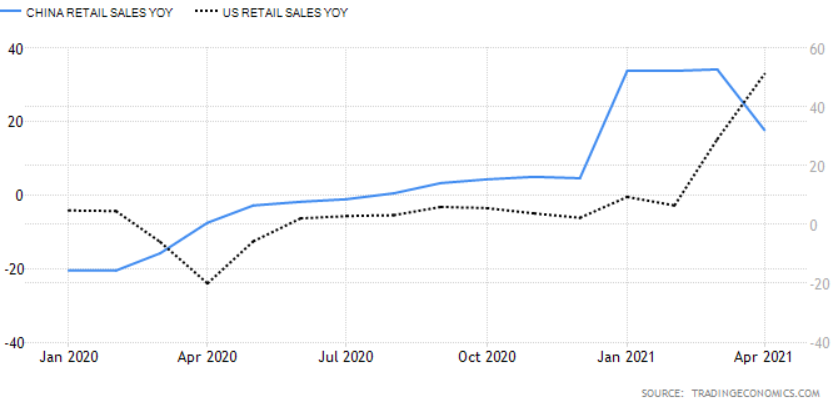

Another sign that official policy measures may be biting was seen in April’s retail sales which, whilst they rose by 17.7%, were down from a 34.2% in March, and came in well below the consensus forecast of 24.9%. Here again, China appears to be a leading indicator of the direction that the US economy might take: –

Source: Trading Economics

Interestingly, unlike 2015, the Chinese stock market has, thus far, reacted in a more measured way to the general tightening of monetary conditions. The next chart shows the relative performance of the Shanghai Composite versus the S&P 500 Index: –

Source: Trading Economics

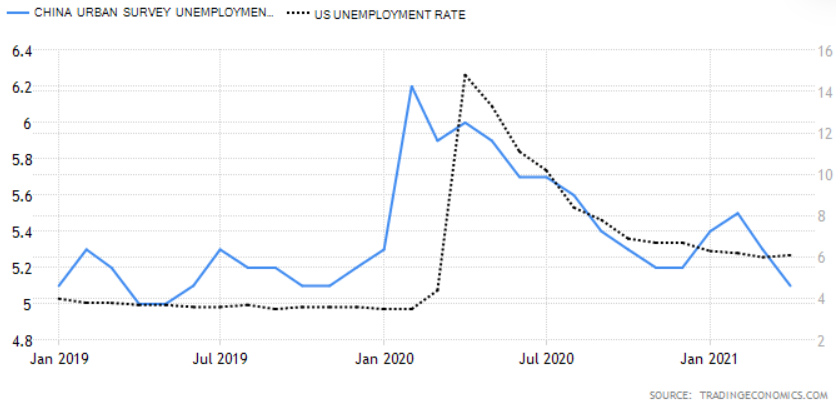

As mentioned above, money supply data points to a slowing of the Chinese economy but, like so many other countries, China saw a sharp rise in its, already high, household saving rate. The Paulson Institute estimates that Chinese households saved 3% more of their income than prior to Covid; Pantheon Macroeconomics equate this pool of savings to roughly 3% of GDP. While many commentators suggest that in China’s case this is a pool of precautionary saving, consumption will likely resume its long-term growth, now that employment prospects have begun to improve. The chart below shows the lagged trajectory of unemployment in US compared to China: –

Source: Trading Economics

US unemployment remains elevated relative to its pre-Covid rate but the economic recovery continues to gather momentum.

In China, as elsewhere, that portion of excess savings not consumed will either be left on deposit, used to reduce debt or invested. Even though interest rates have risen, the liquidity of Chinese capital markets should remain plentiful for the next six months to a year, sufficient to cushion any sudden downturns in the post-Covid recovery.

Conclusions and Investment Opportunities

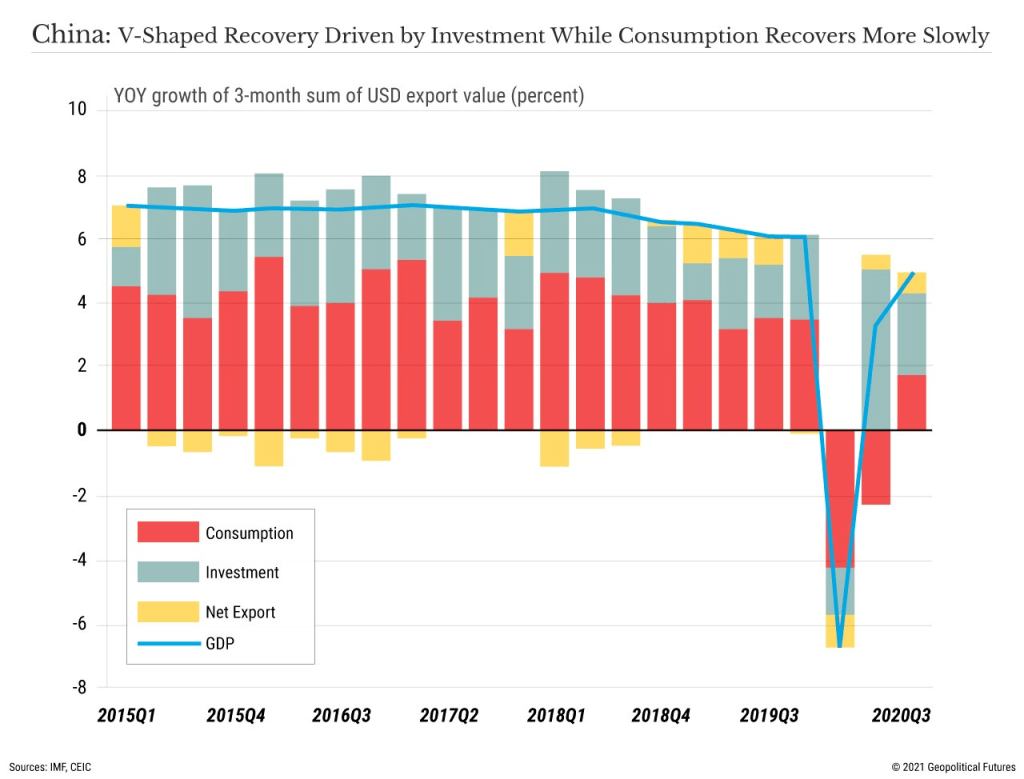

In the analysis above, I have produced a strew of charts suggesting that the US may follow the trajectory of China as the post-Covid recovery unfolds. This is almost certainly too simplistic. Above all else Beijing craves stability, it knows its pace of economic growth is slowing, this is structural. The investment-led growth model which has transformed the economy over the last four decades, requires the methadone of more credit to sustain even these lower rates of return. The policy of rebalancing towards domestic consumption offers longer-term hope, but China’s recovery from the Covid crisis was driven principally by investment and, to a much lesser extent, exports. The chart below, from George Friedman of Geopolitical Futures, shows the damage done to Chinese consumption by the pandemic and the subsequent rebound: –

Source: Geopolitical Futures, IMF, CEIC

The new(ish) US administration is also different from any we have seen for several decades. Markets believe in the arrival of a New New Deal fuelled by a gargantuan monetary and fiscal tonic which will heal-all. Asset prices continue to rise as The Everything Bubble inflates further.

We are still in the early stages of the economic recovery. Supply-chain constraints and labour shortages, even whilst under-employment remains elevated, have driven inflation expectations higher in the near-term, yet asset markets look beyond these shorter-term factors to the productivity gains, which have, in many cases, been a long overdue response to the crisis itself.

A few brave central bankers are seeking to temper the speculative frenzy. The majority, however, will place their emphasis on outcomes rather than the outlookas Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard recently stated. This politically expedient approach means fiat currencies will continue their race to the bottom, bond markets will remain neutered by the policy of QE; that leaves assets as the solitary safety-valve, somewhere between a store of wealth and thar she blows. They afford some protection against debasement and, with the advent of Decentralised Finance, there is a non-zero possibility that some of these assets might even become a means of exchange.

In the near-term we have seen the Norges Bank indicate that it may raise rates in H2 2021. The Bank of Canada has announced a tapering of government bond purchases, inking in a potential rate increase for late 2022, meanwhile the Bank of Japan, whilst it has made no bald statements, has moderated its ETF purchases and stands accused of taper by stealth because the scale of its bond-buying has actually slowed since it adopted yield curve control in 2016. These isolated actions are but clouds in a blue sky of endless liquidity but financial markets prefer to travel rather than to arrive. Choppier markets are likely over the next few months, there may be some excellent asset buying opportunities on sharp corrections.

Macro Letter – No 137

A Review of Stock Market Valuations – Part 2

Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.

Charles Mackay – Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841)

Money is a public good; as such, it lends itself to private exploitation.

Charles Kindleberger – Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises (1978)

Contributing to euphoria are two further factors little noted in our time or in past times. The first is the extreme brevity of the financial memory. In consequence, financial disaster is quickly forgotten. In further consequence, when the same or closely similar circumstances occur again, they are hailed by a new, often youthful, and always supremely self-confident generation as a brilliantly innovative discovery. There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as in the world of finance. Past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present.

JK Galbraith – A short history of financial euphoria (1990)

This is the second of a two part letter reviewing the current valuation of stocks. The focus is US-centric and looks at both long-run valuation (Part 1) and shorter term factors which may be warning signs of irrational exuberance (Part 2).

During the last year we have seen stock markets around the world, decline rapidly and then rebound. Technically the longest bull-market in history ended in March of 2020, but the recovery was so swift that many commentators are calling it merely a sharp correction, simply an aberration. Since March the US stock market, fuelled by aggressive monetary and fiscal easing, has shot to new all-time highs. 2020 ended with the approval of the first Covid-19 vaccines, sending markets higher still.

Equity markets are forward-looking, the economic woes of today are discounted, expectations of recovery, backed by further fiscal support, make the prospects for future earnings appear relatively rosy. In this, the second part of my letter, I want to examine some shorter-term indicators which may or may not be cause for concern that current valuations are a triumph of hope of reality.

I once gave a speech entitled The Trouble with Alpha the gist of which contained my observation that Alpha – that portion of an investment managers returns which are not the result of the performance of the underlying assets was, was simply timing. To arrive at this conclusion I looked at 24 definitions of Alpha, finding that – once I had accounted for factors such as leverage, the ability to be long or short and (of particular importance) the choice of the index which was supposed to represent Beta – all that remained was timing.Suffice to say the speech was not received with acclaim by the audience – who were primarily investment managers. I mention this because, for the majority of investors, the investment time-horizon is finite. It is all very well for me to write about the Long Run and for Warren Buffet to describe his favourite investment horizon being forever, but for most investors, volatility, liquidity and mortality are key.

The economic historian Charles Kindleberger published Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises in 1978, in which he observed patterns of fear and greed stretching back centuries, however, personally, I think Jesse Livermore sums-up the behaviour of financial markets best in the opening pages of Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, published in 1923: –

There is nothing new in Wall Street. There can’t be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again.

In trading especially, but in investment too, timing is (almost) everything.

Show me the signs

There are times when making money from the stock market is hard, and times when it is easy, the latter periods are few and far between, but one of the tell-tale signs that a market has become excessively speculative is when retail investors pile in.

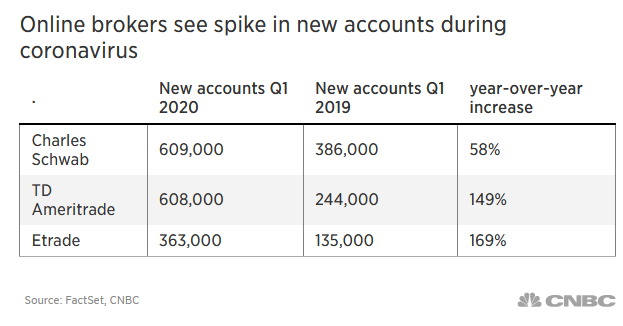

Stock market folk-lore tells of how Joseph Kennedy (although others attribute it to James Pierpont Morgan) decided to sell his stock portfolio ahead of the market crash of 1929. Kennedy figured that when he found himself in receipt of stock tips from his shoeshine boy, the market bubble was very well advanced. The table below shows the uptick in retail stock broker accounts between Q1 2019 and Q1 2020: –

Source: Factset, CNBC

Robinhood is not on the list above, but more on that topic later.

In a recent post – A Visit from the Doom Squad – 10th Man, Jared Dillian quotes research from South Korea on the behaviour of retail stock traders in the aftermath of a bursting stock bubble: –

The researchers observed the behavior of a few thousand of them. After six months, 90% of them had given up. After a year, the 1% who were left barely had enough money to cover their daily expenses.

Dillian believes the biggest risk is of the Federal Reserve becoming more hawkish as the pandemic is brought to heel by the process of mass-vaccination. He concludes: –

That is a real risk. In fact, it is really the only risk, because people correctly point out that the economy will recover strongly in the second half, once most of the vaccines have been distributed.

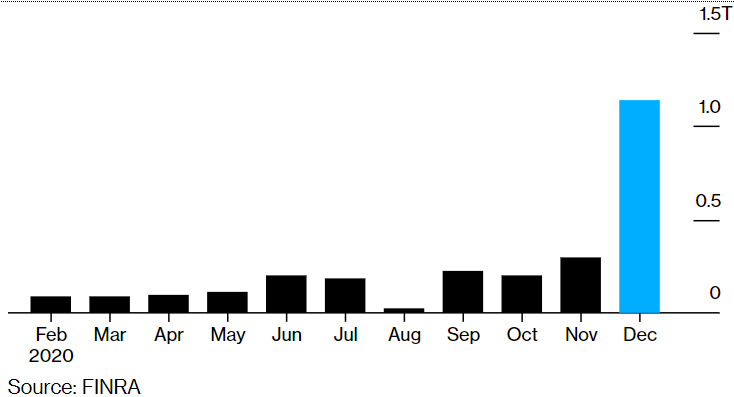

Aside from the proliferation of retail stock-trading accounts, there are several indicators of excessive speculative activity in the US stock market. Firstly, record OTC/Pink Sheet trading volume – these are stocks not listed on the main exchanges: –

Source: Finra, Bloomberg

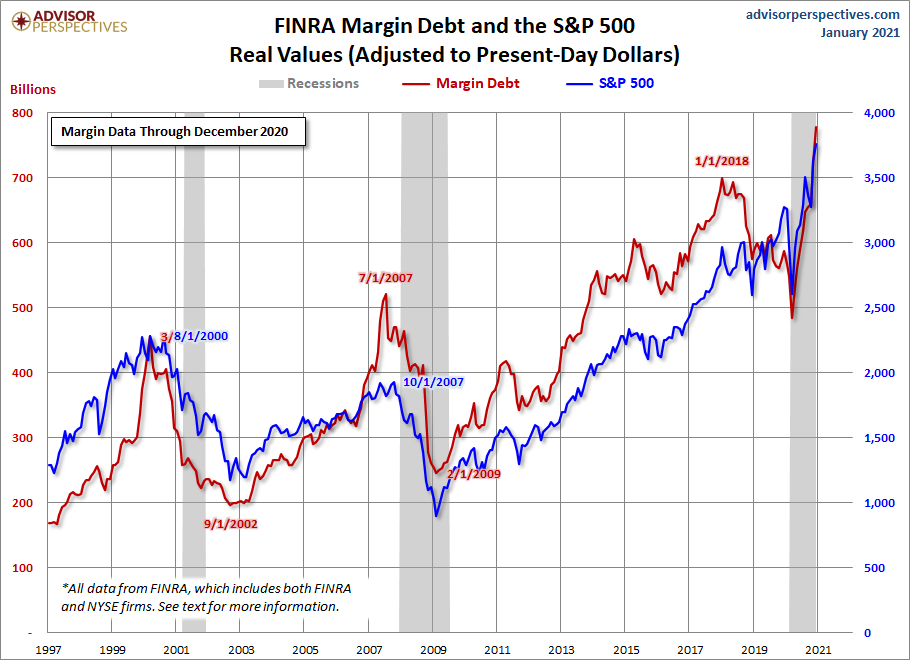

Another bubble warning sign is the record high levels of equity margin trading. The chart below shows the evolution of margin balances and the direction of the S&P 500 index up to December 2020: –

Source: Advisor Perspectives

A further worrying sign of excess is the rise of the SPAC – Special Purpose Acquisition Company. This is a blank cheque shell corporation designed to take a company public without going through the traditional IPO process. SPACs allow retail investors to gain access to private equity type opportunities, particularly leveraged buyouts. A slightly tongue-in-cheek description of the difference between a SPAC and a traditional IPO is that, an IPO is a company in search of capital, whilst a SPAC is capital in search of an investment.

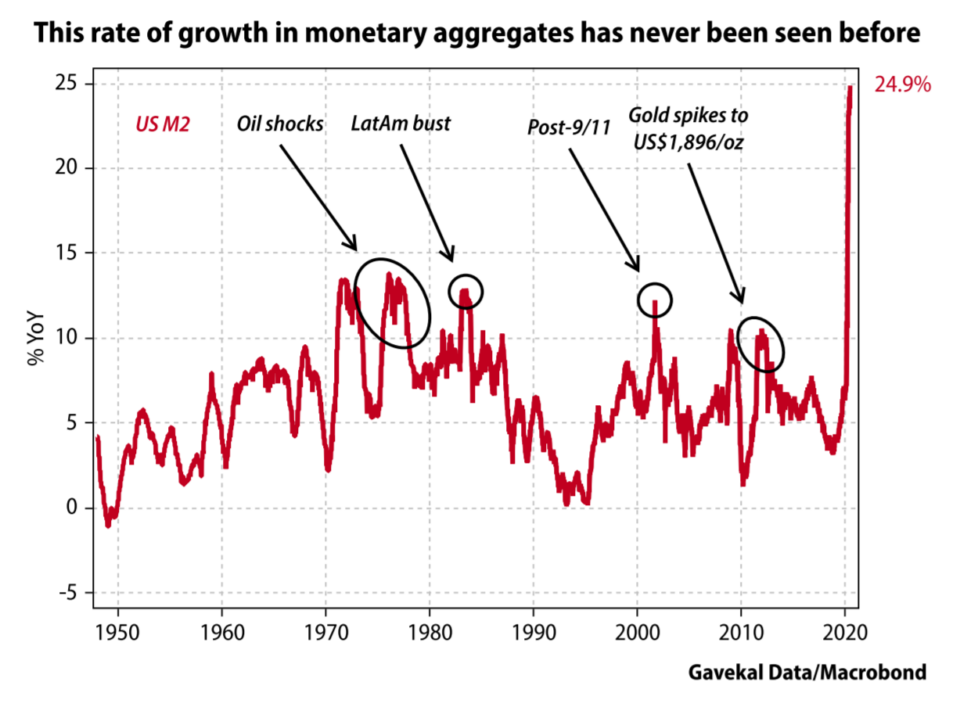

This chart of the ballooning of US money supply growth may help to explain the allure of the SPAC, along with many other signs of speculation: –

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

In 2020, SPACs accounted for most of the growth in the US IPO market, raising $80bln from 237 listings. This surpassed the previous record of $13.6 billion raised from 59 IPOs in 2019. The trend has entered a new phase with $38bln raised from 128 listings in the first six weeks of 2021.

Another outcome of the rapid expansion in money supply can be observed in corporate capital raising. Last December The Economist – A year of raising furiously – noted that corporations globally raised more capital in 2020 than ever before: –

According to Refinitiv, a data provider, this year the world’s non-financial firms have raised an eye-popping $3.6trn in capital from public investors Issuance of both investment-grade and riskier junk bonds set records, of $2.4trn and $426bn, respectively. So did the $538bn in secondary stock sales by listed stalwarts, which leapt by 70% from last year, reversing a recent trend to buy back shares rather than issue new ones.

Here is a chart from the first part of this Macro Letter showing the composition of global corporate capital raising in 2020: –

Source: The Economist

This brings us to the story of GameStop (GME) a video gaming retailer with dismal earnings expectations that was trading at less than $5/share in August of 2020 and peaked at $347/share during a frenzy of hedge fund short covering last month. An excellent description of the time-line and the players involved in the saga can be found in – How Main Street stormed the Financial Capital – the GameStop Story – Vijar Kohli. The GameStop effect spilt over into many small-cap names and pushed the Russell 2000 index to new highs.

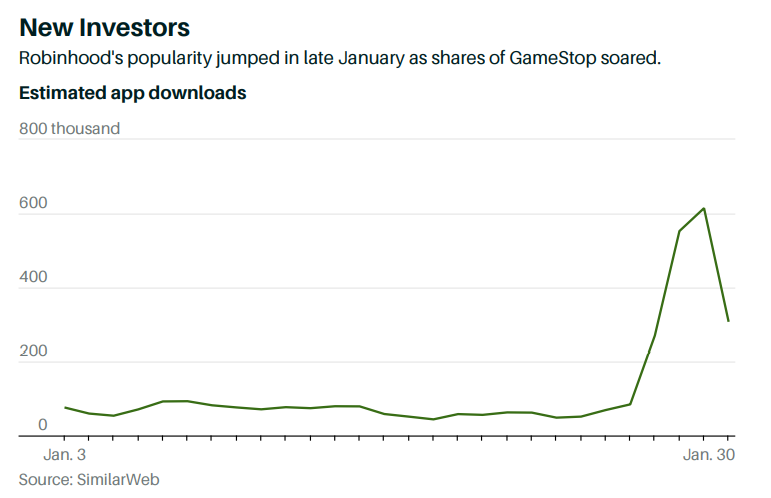

The GameStop tale is intertwined with the fortunes of a retail stockbroker with the beguiling name, Robinhood Financial , and an even more beguiling mobile app. This CNBC article from October 2020 – How Robinhood and Covid opened the floodgates for 13 million amateur stock traders– sheds light on this new phenomenon: –

Robinhood has been the fintech darling of Silicon Valley, founded by Vladimir Tenev and Baiju Bhatt in 2013. The app has amassed 13 million user accounts and led the way for zero-commission fee trading. In no time, it has created brand awareness and popularity unlike that of the legacy brokerages such as Charles Schwab and Fidelity, or its app-first competitors like Webull and Dough.

Despite Robinhood being forced to suspend customer purchases of GameStop, together with some other securities – precipitating an SEC investigation and string of Class Action law suits – the company has continued to take on new clients. According to Rainmaker Securities, the latest private bids for Robinhood shares puts the company’s valuation around $40bln. This February 2021 article from Yahoo Finance – Robinhood is still the app of choice for retail investors: new data– provides more colour. Here is a chart showing the downloads of the Robinhood App last month: –

Source: SimilarWeb, Gavekal

For a more robust economic analysis of the implications of the GameStop saga, Weimin Chen, The Austrian Economic Center – Gamestop Market Mayhem and the Sickness of the Economy is illuminating:. The author concludes: –

There will likely be future limitations placed by brokerage platforms, greater calls for government regulation of the markets, more instances of hysteric market actions, and a general scramble for the next Gamestop style speculation. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was quick to deflect blame for this week’s market volatility, but this could be just the beginning of more upcoming economic turbulence.

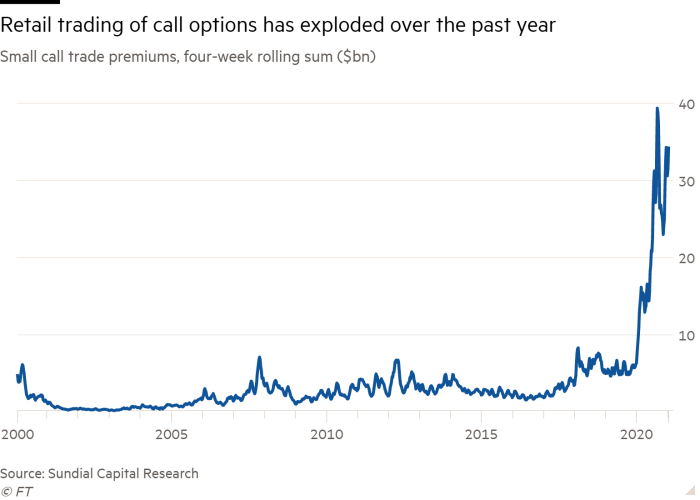

Another feature of the Robinhood Effect has been the dramatic increase in call option trading on single stocks: –

Source: FT, Sundial Capital Research

A common claim is that 90% of options expire worthless, but this is based on the fact that only 10% of option contracts are exercised. According to the CBOE, between 55% and 60% of options contracts are closed out prior to expiration. A more reasonable estimate is therefore that 30-35% of contracts that actually expire worthless. Nonetheless, retail investors have still paid option market-makers a vastly increased amount of option premium during the past year.

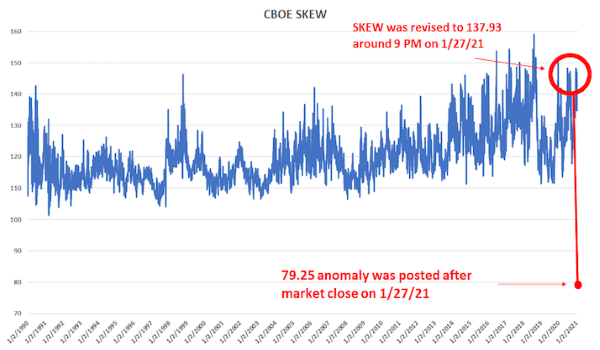

The traded options market is also an important indicator of risk. When the stock market falls, price volatility tends to rise, but option prices can anticipate changes in risk appetite. Without delving too deeply into the dark arts of option trading, in stable market conditions, call options tend to have lower prices (and therefore lower implied volatility) than put options, since investors tend to sell call options against their underlying portfolios but purchase put options to protect themselves from sudden market declines. There is a lot more to option pricing and trading than we can discuss here, suffice to say the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) calculate a SKEW Index – the difference between the relative price of different call and put options. SKEW values generally range between 100 and 150 – the higher the value, the higher the perceived tail risk. A reading of 100 should represent its lower bound (low tail-risk). For a further explanation I defer to David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors – GameStop And SKEW: –

Source: CBOE, Cumberland Advisors

When you examine the SKEW methodology closely, you realize that a 79.25 price is practically impossible. It would mean that the stock market is paying you to take a tail-risk. In other words, such a price means that a trade can be constructed in which the investor cannot lose significantly. This is never supposed to happen. But we see that there is evidence that such a trade may have occurred on the same day as the wild swings of short covering and GameStop trading. That price suggests a market distortion that was quickly multiplied by many times.

Markets are complex systems, the price action in GameStop – and other small cap securities – feeds through to the option market, which in turn impacts other markets. The hedge fund Melvin Capital survived the brutal GameStop short-squeeze to fight another day but the episode is reminiscent, in a more contained way, of the LTCM debacle of 1998 – here is the report of the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets from April 1999 – Hedge Funds, Leverage, and the Lessons of Long-Term Capital Management.

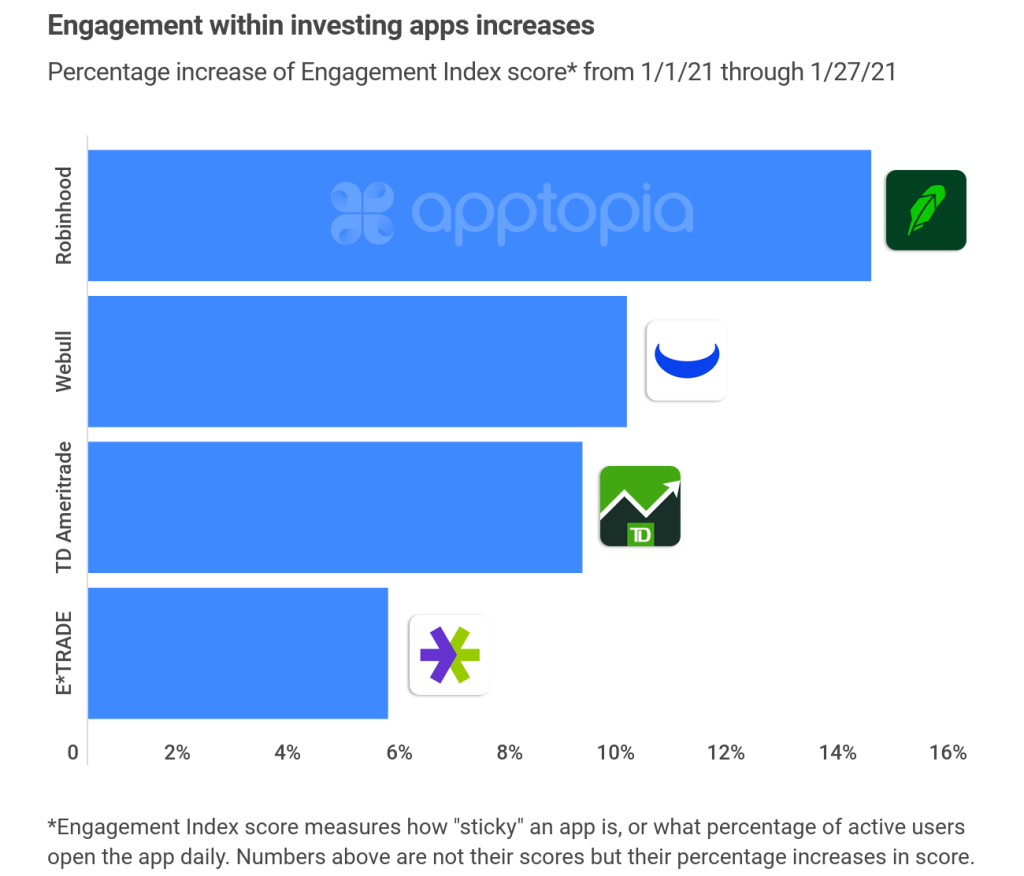

The Robinhood Effect – a lethal mixture of work from home, stay at home and getting a government relief cheque – has been mirrored among other online brokers: –

Source: Horizon Fintex

A similar rise in first-time retail customers is evident in the Cryptocurrency and Foreign Exchange markets.

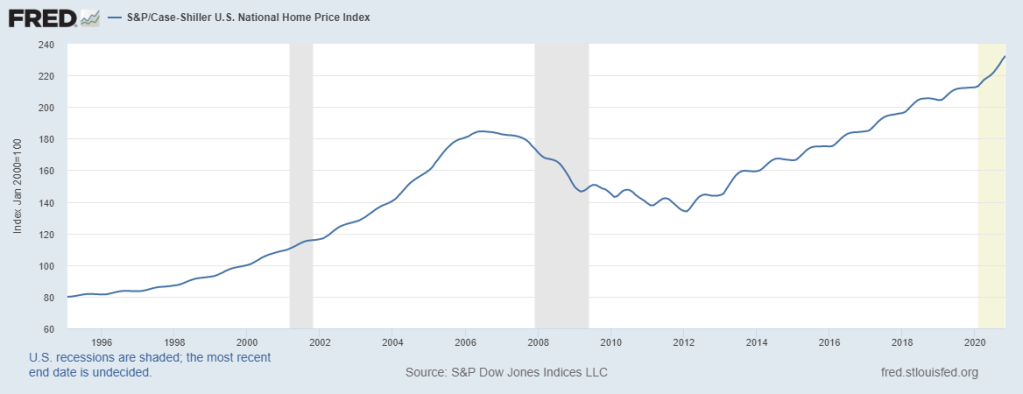

Another sign of assets being in bubble territory is the performance of the housing market. Now, it goes without saying, all property is local, but looking at the US, where the fiscal and monetary response has been the largest, we find yet another asset market at an all-time high: –

Source: Federal Reserve

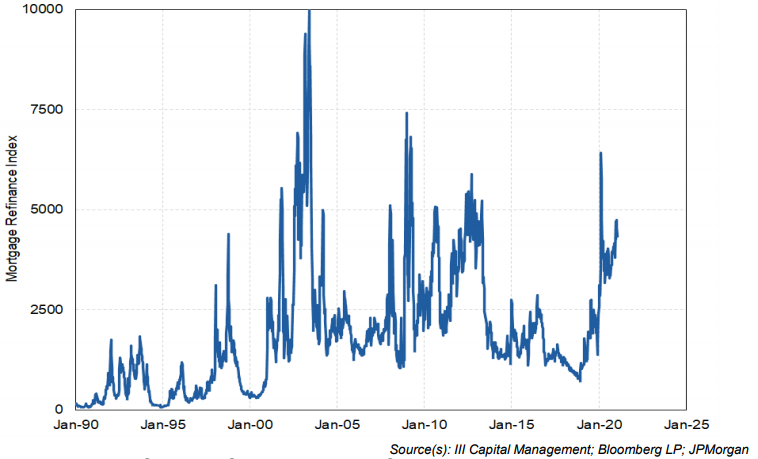

The rise in house prices has been fuelled by cheap money: –

Source: III Capital Management, Bloomberg, JP Morgan

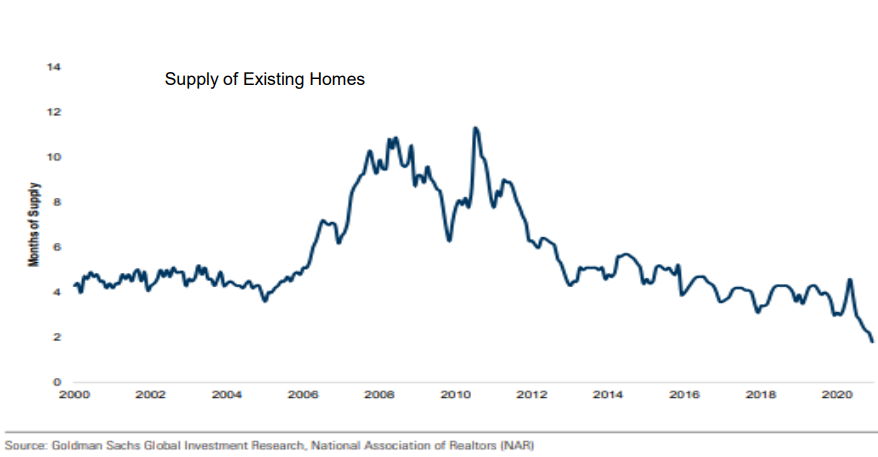

Combined with a shortage of supply: –

Source: III Capital Management, Goldman Sachs, NAR

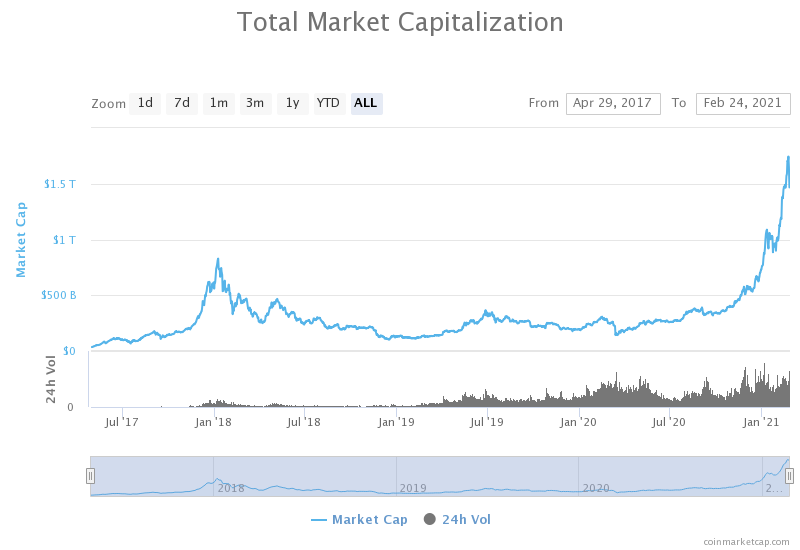

Finally, fiscal and monetary expansion is akin to fiat currencies have debasement, it is scant surprise, therefore, to see Cryptocurrencies resurgent. The chart below shows the combined market capitalisation of all the listed digital currencies: –

Source: Coinmarketcap.com

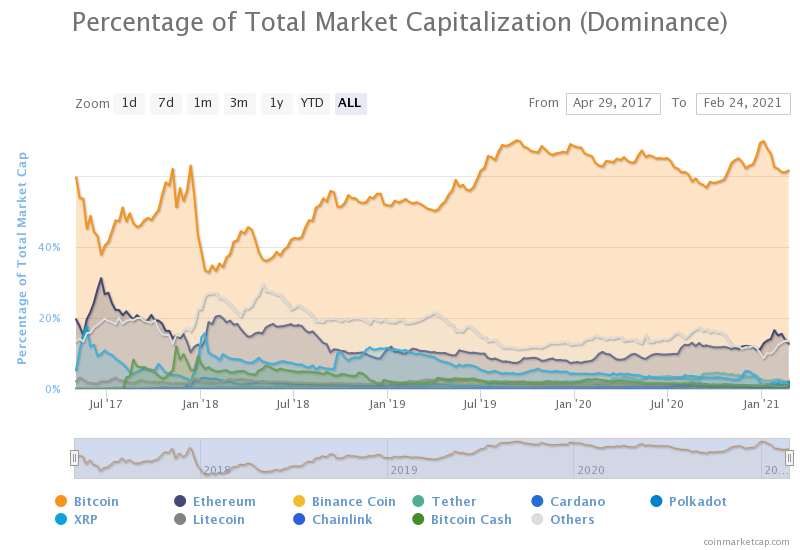

Of course the principal focus of the media has been on Bitcoin (BTC) access to which was made available to Paypal customers from October 2020. This month’s big stories include Telsa (TSLA) purchasing $1.5bln of BTC during January and Mastercard indicating that they intend to accept BTC as a form of payment later this year. The next chart shows the rising dominance of BTC (61%) compared to the previous peak in 2017: –

Source: Coinmarketcap.com

Ethereum (ETH) is second with a mere 12.7%. Putting digital assets in perspective, however, the market capitalisation of BTC, which just topped $1trln last week, is still less than 10% of the total market capitalisation of gold.

Whether or not one regards digital assets as an alternative store of value, soon to displace what Keynes dubbed the barbarous relic (gold), it is incontrovertible that the digital asset industry is in its infancy whilst the underlying technologies – DL, Blockchain and DeFi – have the potential to disrupt the entire financial system – who needs banks or other financial intermediaries in this brave new decentralised world? Coinbase, which has been described as the Robinhood of the Crypto world, is planning an IPO for later this year. The current indication is that it will achieve a capitalisation of $77bln.

What is of concern is that the Crypto charts above wreak of euphoria. Traders and investors with no prior experience, have jumped on the trend and now command cult-like status among the ingénue. Some of their followers will be lucky, but these price patterns are the tell-tale traits of a greater fool’s marketplace.

Even in the liquid, large-cap names, echoes of the DotCom bubble are apparent. Apple (AAPL) and Tesla (TSLA) stock rose more than 50% in the days after they announced stock splits. Apple created more value for shareholders by announcing a stock split in 2020 than through its new product launches, Tesla, which declared the first profit in its 18 year existence in 2020 ($721mln) has made more from its purchase of Bitcoin than it has made in its lifetime.

In a recent post, on what many have dubbed the everything bubble, – Is This The Biggest Financial Bubble Ever? Hell Yes It Is – John Rubino concludes: –

Meanwhile, the actions necessary to fix some of these bubbles are mutually exclusive. A stock market or housing bust requires much lower interest rates and bigger government deficits, while a currency crisis brought on by rising inflation requires higher interest rates and government spending cuts. Let everything blow up at once and there will be literally no fixing it. And the “everything bubble” will become the “everything bust.”

John’s website is called Dollar Collapse, of the two end-games he outlines above, letting the US$ slide is the least painful short-term solution, no wonder the US administration keep labelling other countries currency manipulators.

The Stock Market’s Nemesis

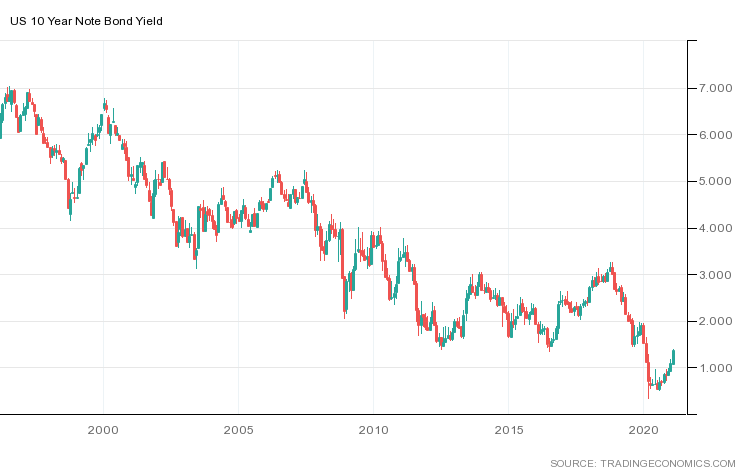

Having lain dormant for so long, its return to prominence may come as a shock to newer participants in the stock market: I am of course referring to the US Treasury Bond market. The chart below shows the 10yr yield over the last quarter century: –

Source: Trading Economics

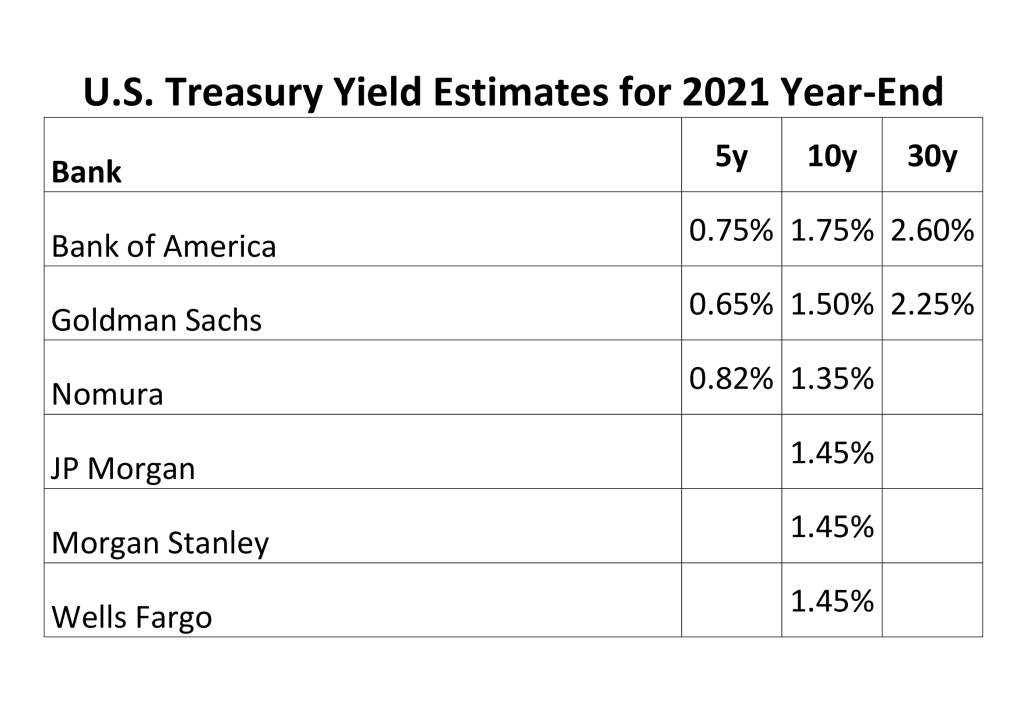

10yr yields hit their all-time low at 32bp last March, today (24th February) they have risen to 1.39%. The table below shows a selection of forecasts for year-end yields: –

Source: III Capital Management

Central Bankers are holding short-term rates near to zero but the longer end of the yield-curve is being permitted to express concerns about the inflationary consequences of excessively accommodative fiscal and monetary policy. Meanwhile, central bank buying of corporate bonds has insured that credit spreads have shown a muted response to the recent increase in yields. At some point there will be an inflection point and credit will reprice violently. For those adventuring in the stock market, these words attributed to James Carville – a political adviser to President Clinton – remain worthy of careful reflection: –

I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.

Unless, as I expect, the world’s leading central banks intervene to fix the price of government bonds, the bond market, left to its own devices, will bring the stock market back to reality with a crash.

Conclusion and Investment Opportunities

Having written more than 6,000 words in this two part Macro Letter I still feel as if I have merely scratched the surface of the conflicting and contrasting factors which support the bull and bear case. Taking a step back, I encourage you to read Five Lessons From History By Morgan Housel, The Collaborative Funda short-ish article which presents five lessons which can be applied to investing and to life in general. In the interests of brevity: –

Lesson #1: People suffering from sudden, unexpected hardship are likely to adopt views they previously thought unthinkable.

Lesson #2: Reversion to the mean occurs because people persuasive enough to make something grow don’t have the kind of personalities that allow them to stop before pushing too far.

Lesson #3: Unsustainable things can last longer than you anticipate.

Lesson #4: Progress happens too slowly for people to notice; setbacks happen too fast for people to ignore.

Lesson #5: Wounds heal, scars last.

Reflecting on the current great viral crisis (GVC) and its aftermath, I see many signs of irrational exuberance but remain cognisant of the low likelihood of any sudden policy reversals by developed nation governments or their central banks, this is primarily due to the fragility of the current global economy. The scars of Covid will take many years to heal, unsustainable things may last longer than anticipated and, as JM Keynes famously observed: –

The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.

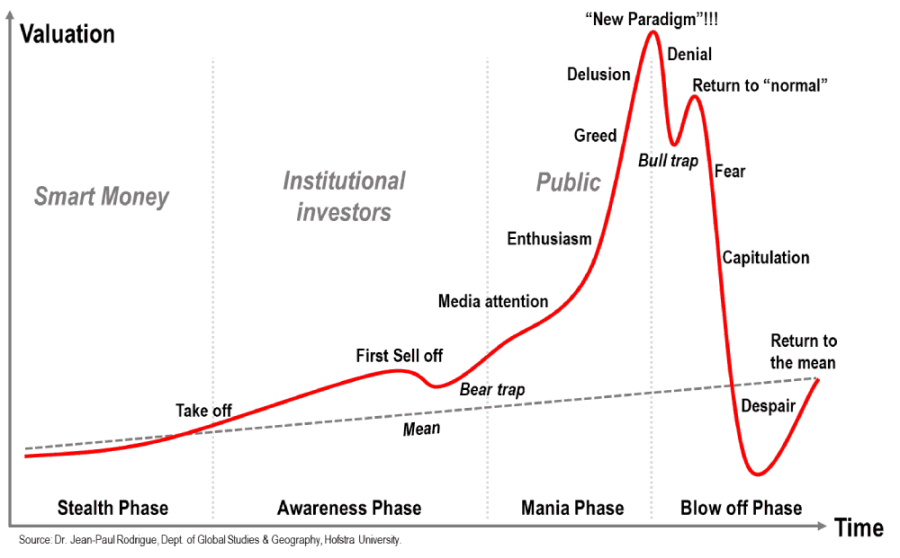

The cult of the personality, personified by the likes of Elon Musk, remains ascendant, so reversion to mean may be postponed a while. There is widespread evidence of what the French philosopher Rene Girard dubbed mimetic desire; the idea that, because people imitate one another’s desires, they tend to desire the same things; in the process this desire creates rivalry and increases the fear of missing out. In the classic evolution of a bubble mimetic desire leads from the momentum or awareness phase to the hallowed halls of mania and euphoria: –

Source: Dr Jean-Paul Rodrigue – Holstra University

Now is not the time to be rushing headlong into the stock market, but the upward trend remains firmly in tact. Alan Greenspan observed irrational exuberance in 1996, it took the market another four years to reach its high, mimetic desire makes it hard for investors to risk taking profit for fear of missing an exponential rise. There are several risk reduction strategies, but these statements, attributed to two of the most successful investors of all time are always worth keeping in mind: –

Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.

Warren Buffett

The time of maximum pessimism is the best time to buy and the time of maximum optimism is the best time to sell.

Sir John Templeton

Macro Letter – No 135 – 31-12-2020

US Stocks in 2020 and the prospects for 2021

The US stock market is making all-time highs (as at 29th December). It has been a torrid year. The 35% shakeout in the S&P 500, seen in March, turned out to be the best buying opportunity in several years. The market recovered, despite the human tragedy of the pandemic, fuelled by a cocktail of monetary and fiscal stimulus. When news of the rollout of a vaccine finally arrived in November, apart from a renewed rise in the broad market, there was an abrupt rotation from Growth to Value stocks. Value ETFs saw $8bln of inflows during November, there was also a weakening of the US$ and resurgence of European stocks. This was not necessarily the sea-change anticipated by many commentators, by the start of December technology stocks had resumed their upward march.

November marked some market records. It was the strongest month for the Dow since 1987 and the best November since 1928. European stocks rose 14%, their best monthly gain since April 2009 – that headline grabbing performance needs to be qualified, European indices remain lower than they began the year. For Japan’s Nikkei 255, the 15% rise marked its most positive monthly performance since January 1994, whilst for Global Equities, which returned 12.7%, it was the best month since January 1975.

Other financial and commodity markets also reacted to the vaccine news. OPEC agreed supply reductions helping oil prices higher, although Brent Crude remains around 22% lower than it started the year. The larger issue for stock markets is the logistical challenge of delivering the vaccination, this will test the healthcare systems of every country on the planet. The OPEC deal may fray at the edges, demand for oil could arrive later than anticipated. Nonetheless, risk assets have generally benefitted whilst both gold and silver have remained range-bound. After their strong rally in the summer, precious metals seem to have had their time in the sun. Interestingly, Bitcoin appears to be dancing to a different tune. Over the past two months it has risen more than 120%, breaking the previous highs of December 2017 to breach $28,000.

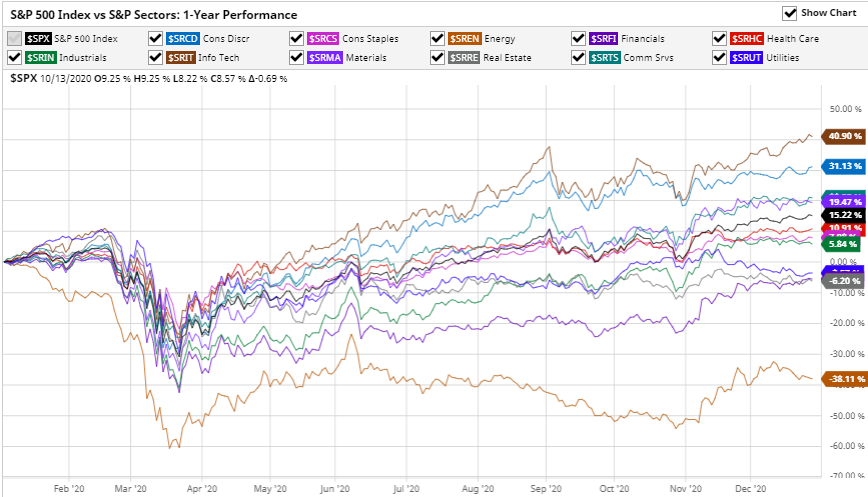

Looking ahead, Covid sensitive stocks should continue to recover, this chart shows the relative performance by industry sector over the last year (to 29th December): –

Source: Barchart.com, S&P

Energy, November’s top performing sector, remains more than 38% down over the last 12 months, whilst Information Technology is up almost 41% over the same period.

Prospects for 2021

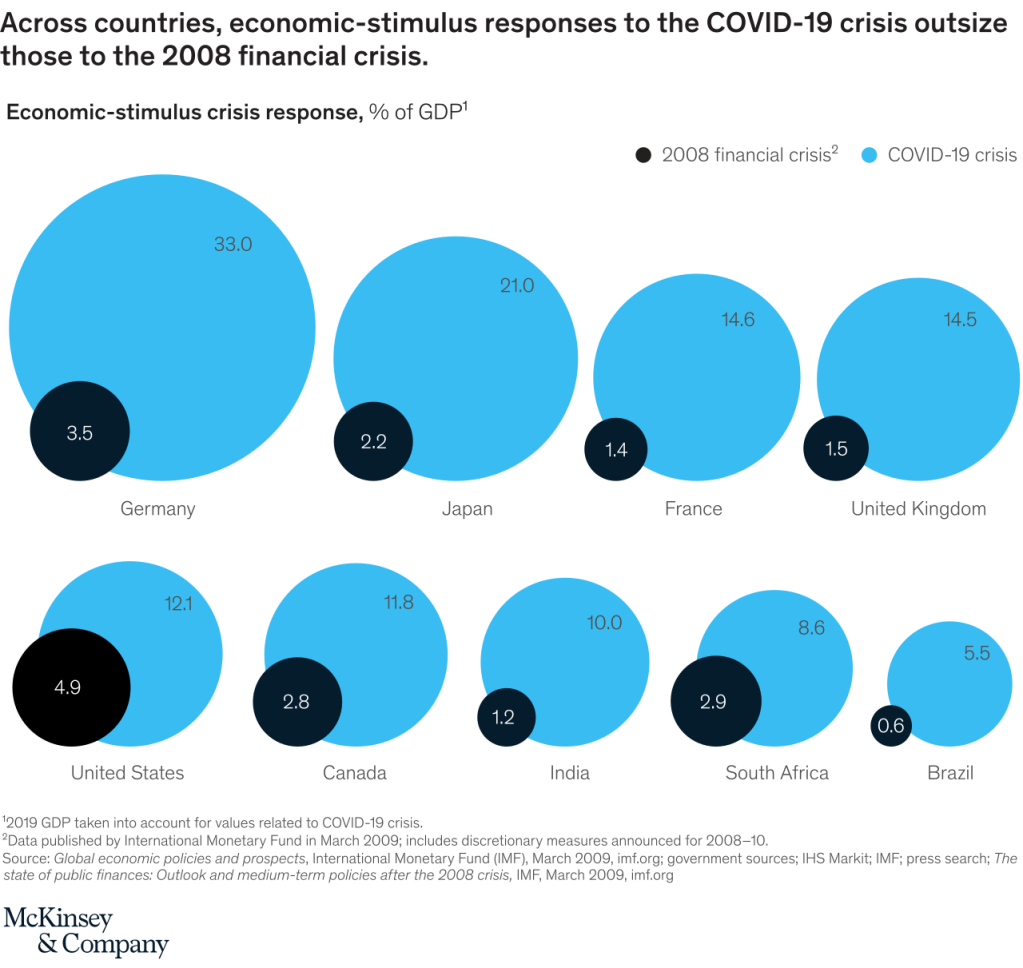

Central bank monetary policy and developed nation fiscal policy will be key to deciding the direction of stocks next year. This infographic from McKinsey shows the gargantuan scale of the fiscal response compared to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008: –

Source: McKinsey, IMF

The degree of largesse needs to be qualified, more than half of government support has been in the form of guarantees, designed to help companies avoid insolvency. Added to which, other stimulus measures have been announced, but that capital has yet to be been committed. The eventual bill for the pandemic might not be quite the strain on collective international government finances the McKinsey infographic portends. This chart from the IMF shows the composition of fiscal support as at mid-May: –

Source: IMF

A more important factor for global stocks is the enormous injection of liquidity which has been pumped into the world economy: –

Source: Yardeni

This global picture disguises the variance between countries: –

Source: Federal Reserve, National Central Banks, Haver Analytics, Globalization Institute

With the exception of the US, money supply growth has been relatively muted thus far, although it has been broadly comparable to the expansion undertaken in the aftermath of the sub-prime crisis of 2008. The vast expansion of the US monetary base is unprecedented by comparison with its developed nation peers, but even more so when seen in the context of US policy since WWII: –

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

Money supply growth cannot be ignored when seeking a reason for the rise in US stocks. North American asset markets, such as stocks and real estate, will continue to benefit even if some of that liquidity seeps away to international investment opportunities. The Cantillon Effect, named after 18th century Irish economist, Richard Cantillon, remains very much alive and well. In Cantillon’s – Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en General – which was published posthumously in 1755 – he observed that those who were closest to the minting of money benefitted most.

Today, with unemployment sharply higher and lockdown restrictions curtailing consumption, the US savings rate has risen sharply. Even after hitting a peak in April it remains well above the levels seen since the 1970’s. The chart below does not account for the effect of the recent relief package which will release a further $900bln, including cheques to many individuals of $600 each: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

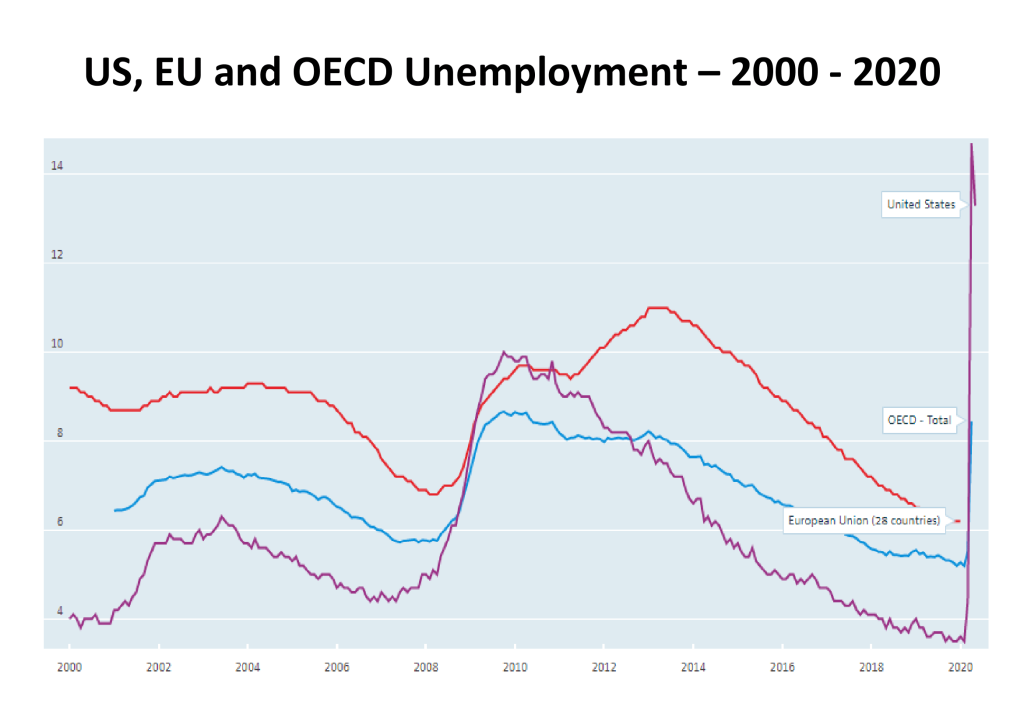

Whilst the unemployment rate remains elevated, that excess liquidity will either be hoarded or flow into the stock market, in these uncertain times it is unlikely to fuel a consumption boom. This chart shows how unemployment rates have increased across the US, EU and OECD countries in aggregate: –

Source: OECD

Aside from a short-lived boom in the grocery sector at the start of the crisis, US consumer spending remained muted running into the summer: –

Source: NEBR

The situation improved in Q3 as the inforgraphic below reveals: –

Source: Deloitte, BEA, Haver Analytics

Real personal consumer expenditure grew by 8.9% in Q3 compared to Q2. The nature of consumer spending has also changed as a result of the pandemic, with many consumers buying relatively more goods than services. Without reliable data it is difficult to assess the picture for Q4, but the second wave of Corona cases appears to be a worldwide phenomenon, a repeat of the April/May lockdown may yet defer the much anticipated recovery in consumption.

Investment Opportunities for 2021

Looking ahead, the first important test of US political sentiment will be the runoff Senate race in Georgia on January 5th. Nonetheless, for the coming year, with government bond yields still miserably low, excess liquidity will continue to flow into stocks. The recent weakening of the US$ may lend additional support to international markets, especially if Europe stops its squabbling and embraces fiscal expansion. Dollar bulls might just be rescued by the US bond market, 10yr yields reached 99bps at the beginning of December, the highest since the pandemic struck in March, yields have remained elevated with a fresh stimulus package to finance, but an economic recovery remains some way off, a real bond bear-market needs a significant inflation catalyst.

As Milton Friedman famously observed, ‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ Even allowing for a strong rebound in demand for goods and services in 2021, the consumer will remain cautious until mass-vaccination has proved to be effective. Meanwhile, that excess liquidity will have to go somewhere, all other things equal, asset markets will rise with liquid, listed equities in the vanguard.

Macro Letter – No 134 – 27-11-2020

Relax, Rotate, Reflate

November has been an interesting month for financial markets around the world. The US Presidential election came and went and with its passing financial market uncertainty diminished. This change of administration is undeniably important, but its effect was overshadowed by the arrival of three vaccines for Covid-19. As I write (Thursday 26th) the S&P 500 Index is within 30 points of its all-time high, amid a chemical haze of pharmaceutical hope, whilst the VIX Index has tested its lowest level since February (20.8%). The Nasdaq Composite is also near to its peak and the Russell 2000 Index (an index of smaller capitalisation stocks) burst through its highs from February 2020 taking out its previous record set in September 2018. The chart below shows the one year performance of the Russell 2000 versus the S&P500 Index: –

Source: Yahoo Finance, S&P, Russell

It is worth remembering that over the very long term Small Caps have outperformed Large Caps, however, during the last decade the rapid growth of index tracking investments such as ETFs has undermined this dynamic, investment flows are a powerful force. I wrote about this topic in June in – A Brave New World for Value Investing – in which I concluded: –

Stock and corporate bond markets have regained much of their composure since late March. Central banks and governments have acted to ameliorate the effects of the global economic slowdown. As the dust begins to settle, the financial markets will adjust to a new environment, one in which value-based stock and bond market analysis will provide an essential aid to navigation.

The geopolitics of trade policy, already a source of tension before the pandemic struck, has been turbo-charged by the simultaneous supply and demand shocks and their impact on global supply chains. Supply chains will shorten and diversify. Robustness rather than efficiency will be the watch-word in the months and years ahead. This sea-change in the functioning of the world economy will not be without cost. It will appear in increased prices or reduced corporate profits. Value-based investment analysis will be the best guide in this brave new world.

To date, evidence of a return to Value Investing seems premature, Growth still dominates and the structural acceleration of technology trends seems set to continue – one might say, ‘there is Value in that.’

The vaccine news led to a rotation out of technology stocks but this was more to do with profit taking, new ‘Tech’ buyers quickly emerged. The rotation into Small Caps was also echoed among a number of out of favour sectors such as Airlines and Energy. It was enough to prompt the creation of a new acronym – BEACHs – Booking, Entertainment, Airlines, Cruises and Hotels.

Source: Barchart.com, S&P

Above is the one year performance of the 11 S&P 500 industry sectors. Information Technology remains the leader (+38%) with Energy bringing up the rear (-32%) however the level of dispersion of returns is unusually which has presented an abundance of trading opportunities. The table below shows the one, three and six month performance for an expanded selection of these sectors: –

Source: Tradingview

Beyond the US, news of the vaccines encouraged both European and emerging markets, but the latter (EEM), helped by the strong performance of Chinese stocks, have tracked the US quite closely throughout the year, it is Europe (IEUR) which has staged the stronger recovery of late, although it has yet to retest its February highs: –

Source: Yahoo Finance, S&P, MSCI

In the aftermath of the US election, US bond yields have inched higher. From an all-time low of 32bp in March, 10yr yields tripled, testing 97bp in the wake of the Democrat win. Putting this in perspective, the pre-Covid low was seen at 1.32% in July 2016. The current concern is partly about the ‘socialist’ credentials of President-elect, Biden, but the vaccine announcement, together with the prospect of a return to some semblance of normality, has also raised the spectre of a less accommodative stance from the Fed. There was initial fear they might ‘take away the punch-bowl’ before the global economy gets back on its knees, let alone its feet. Governor Powell, quickly dispelled bond market fears and yields have since stabilised.

Longer-term, these bond market concerns may be justified, as this infographic from the McKinsey Institute reveals, combined central bank and government fiscal stimulus in 2020 has utterly eclipsed the largesse witnessed in the wake of the 2008 crisis: –

Source: McKinsey

Bond watchers can probably rest easy, however, should the global economy stage the much vaunted ‘V’ shaped recovery economists predicted back in the spring, only a fraction of the fiscal stimulus will actually materialise. Nonetheless, prospects for mass-vaccination, even in developed countries, remains some months away, both monetary and fiscal spigots will continue to spew for the present.

On the topic of monetary policy it is worth noting that the Federal Reserve previously employed ‘yield curve control,’ though it was not called by that name, back in April 1942, five months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Under this arrangement the Fed committed to peg T-Bills at 3/8th and implicitly cap long-dated T-Bonds at 2.5%. The aim was to stabilize the securities market and allow the government to engage in cheaper debt financing during the course of WWII. This arrangement only ended with the Treasury – Fed Accord of 1951 in response to a sharp peace-time resurgence in inflation. This chart shows the period from 1941 (when the US entered WWII) up to the middle of the Korean War: –

Source: US BLS

I believe we will need to see several years of above target inflation before the Fed to feel confident in raising rates aggressively. The experience of Japan, where deflation has been lurking in the wings for decades, will inform Fed decision making for the foreseeable future.

Returning to the present environment; away from the stock and bond markets, oil prices also basked in the reflected light shining from the end of the pandemic tunnel. West Texas Intermediate, which tested $33.64/bbl on 2nd, reached $46.26/bbl on 25th. The energy sector remains cautious, nonetheless, even the recent resurgence leaves oil prices more than $15/bbl lower than they were at the start of the year.

Looking ahead, the stock market may take a breather over the next few weeks. A vaccine is coming, but not immediately. US politics also remains in the spotlight, the Republicans currently hold 50 Senate seats to the Democrats 48. If Democrats secure the two seats in Georgia, in the runoff election on 5th January, VP Elect, Harris, will be able to use her ‘tie-break’ vote to carry motions, lending the Biden Presidency teeth and hastening the expansion of US fiscal policy.

The stock market has yet to make up its mind about whether Biden’s ‘New New Dealers’ are a positive or a negative. Unemployment and under-employment numbers remain elevated as a result of the pandemic: and, whilst bankruptcies are lower than at this time last year, the ending of the myriad schemes to prolong the existence of businesses will inevitably see those numbers rise sharply. Does the stock market benefit more from the fiscal spigot than the tax increase? This is a question which will be mulled, chewed and worried until long after Biden’s inauguration on January 20th.

Meanwhile the trend accelerations in technology which I discussed in – The prospects for Emerging and Frontier Markets in the post-Covid environment – earlier this month, continue. The chart below shows how information industries have been transforming the makeup of global trade ever since the great financial crisis: –

Source: ECIPE, OECD, TiVA, van der Marel

Manufacturing trade is in retreat, trade in digital services is accelerating. The chart above stops at 2015, when we have the data to incorporate the period of the current pandemic, I expect the pace of growth in information industries to have gain even greater momentum.

Back in 1987, MIT economist and Nobel Laureate, Robert Solow, observed that the computer age was everywhere except for the productivity statistics. During the 1990’s technology productivity growth was finally observed, but the past decade has seen a string of disappointing productivity growth statistics, yet they have coincided with digitisation transforming vast swathes of the global economy, perhaps the next decade will see the fruit of these labours. I believe we can look forward to significant productivity improvements in the coming years. Stock prices, however, are forward looking, their valuations may seem extended but this may be entirely justified if technology ushers in a new golden age.

Macro Letter No 132 – 04-09-2020

Step-change at the Fed – Reaching for the stars

In a speech entitled – New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review – given on August 27th, at the Jackson Hole, Kansas City Federal Reserve Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell, announced a change in the emphasis of the dual mandate. The new focus is on promoting full-employment even at the expense of price stability.

The policy review was, of course, more nuanced. Past policy decisions were analysed and found wanting – especially the rate increases witnessed between 2015 and 2018. The extraordinary flatness of the Phillips Curve was noted; the lower trend rate of economic growth, contemplated; the stickiness of inflation expectations, contextualised: and the ever rising, pre-pandemic participation rate, considered. What the speech omitted was any discussion of forward guidance or expectations of the change in size, composition or direction of the Fed’s, already historically large, balance sheet.

For financial markets the key change is contained in this paragraph: –

Our statement emphasizes that our actions to achieve both sides of our dual mandate will be most effective if longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent. However, if inflation runs below 2 percent following economic downturns but never moves above 2 percent even when the economy is strong, then, over time, inflation will average less than 2 percent. Households and businesses will come to expect this result, meaning that inflation expectations would tend to move below our inflation goal and pull realized inflation down. To prevent this outcome and the adverse dynamics that could ensue, our new statement indicates that we will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time. Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

The initial market response saw stocks rally whilst 10yr T-bond yields rose – testing 0.79%. During the week which followed, 10yr yields slipped back to 0.62%. Equity markets subsequently switched focus and moved on, returning to their obsession with the ever rising tide of technology stock earnings expectations. Even the Dow Jones Industrials Average Index has been effected by the tech boom, as reported by S&P – Dow Jones Industrial Average: 124 Years and It Keeps Changing – the index changes, announced on August 31st included, Salesforce.com (CRM) replacing Exxon Mobil (XOM), Amgen (AMGN) replacing Pfizer (PFE), and a tech switch with Honeywell International (HON) replacing Raytheon Technologies (RTX).

Returning to monetary policy, the Fed announcement was hardly a surprise, the August 10th, FRBSF Economic Letter – Average-Inflation Targeting and the Effective Lower Bound had already set the tone. The chart below reveals the Fed’s inflation targeting dilemma: –

Source: FRBSF

If the average for Total PCE over the last decade has been less than 1.5%, allowing it to rise above 3% for a few years is just what is needed for the Fed to get back on track.

Setting aside the vexed questions of whether an Inflation Target is appropriate or, deflation, a good or bad phenomenon, we need to investigate the structural cause of the decline in inflation. Here I will resort to the monetary equation of exchange: –

MV = PQ

Where: –

M is the total nominal amount of money supply in circulation on average in an economy.

V is the velocity of money, or the average frequency with which a unit of money is spent.

P is the price level.

Q is an index of real expenditures for newly produced goods and services.

The basic problem for the Fed is that, despite their success in expanding money supply (see below): –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

The velocity of circulation has continued to plummet: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

I discussed the rapid expansion of money supply in more detail in a June article for AIER – Global Money Supply Growth and the Great Inflation Getaway: –

I suspect, fearful of repeating the mistakes made by the Bank of Japan, that once the inflation genie is finally out of the bottle, central bankers will forsake the hard-learned lessons of the 1970’s and 1980’s and allow inflation to conjure away the fiscal deficits of their governments at the expense of pensioners and other long-term investors.

Of course, consumer price inflation may not return, even with such egregious debasement as we have seen thus far, as Michel Santi suggests in Japan: a sleeping beauty: –

A global battle has thus been raging on pretty much since the deflationary episodes of the 2010s in an attempt to relaunch economies by dint of inflation. In this respect, the Japanese experiment, or rather multiple experiments, remains a case study to show that inflation is still proving a difficult spectre to revive.

Santi, points to demographic decline, a trend in which Japan is a world leader, together with, what he considers to be, an irrational fear of debt and deficits, which renders people unwilling to spend. In this scenario, government, corporate and consumer debt cannot be inflated away and sits like a giant toad atop all the animal spirits that might reignite economic growth. He also alludes to the profound changes in the nature of work – from permanent to temporary, from employed to self-employed, from office based to remote. These changes have rendered the Phillips Curve redundant.

The dual mandate of full employment and price stability has never been so easy for the Federal Reserve to achieve. That, at least, was the case until the global pandemic unknit the fabric of the global market economy. Now, the Federal Reserve – and central bankers in general – are faced with the prospect that printed money, whether it be sterilised or not, will either be invested or hoarded. In this scenario, the greater the debt the less likely prices are to rise as a result of demand-pull inflation. On the opposite side of the inflation equation, the shortening of global supply chains and the need for dual-redundancy, agin another unwelcome and unexpected lockdown, has created the classic bottlenecks which lead to product scarcity, personified in cost-push inflation.

Interest Rates, Global Value Chains and Bank Reserve Requirements– published in June of last year, notes that Global Value Chains have suffered and shortened since 2009; that, despite low interest rates, financing costs remain too high and yet, at the same time, bank profitability has not recovered from the damage caused by the great financial recession. Nonetheless, those same banks, which were supposed to have been broken up or dramatically deleveraged, remain still too big to fail. My conclusion looks dismally prescient: –

The logical solution to the problem of the collapse of global value chains is to create an environment in which the credit cycle fluctuates less violently. A gradual normalisation of interest rates is the first step towards redemption. This could be accompanied by the removal of the moral hazard of central bank and government intervention. The reality? The societal pain of such a gargantuan adjustment would be protracted. It would be political suicide for any democratically elected government to commit to such a meaningful rebalancing. The alternative? More of the same. Come the next crisis central banks will intervene, if they fail to avert disaster, governments’ will resort to the fiscal spigot.

US interest rates will converge towards those of Europe and Japan. Higher stock/earnings multiples will be sustainable, leverage will increase, share buy-backs will continue: and the trend rate of economic growth will decline. Economics maybe the dismal science, but this gloomy economic prognosis will be quite marvellous for assets.

Conclusion and Investment Opportunities

According to data from S&P, US share buybacks were lower for the second quarter in a row in Q2, 2020. They amounted to $166bln, versus $205bln in Q1 and $190bln in Q2, 2019 – this is still the seventh highest quarterly amount ever recorded. The chart below shows the evolution of buybacks over the last two decades: –

Source: S&P, FT

The consolidation of the US equity market continues – from a high of 7,562 on July 31, 1998, the Wilshire 5000 Index list of constituents has shrunk to just 3,473 names. This is a side effect of the fact that debt finance remains cheaper than equity finance. According to a recent article published by the Financial Times – US corporate bond issuance hits $1.919tn in 2020, beating full-year record corporate issuers have raised more capital in the first eight months of 2020 than in any previous full year. Low rates going to no rates, thanks to the actions of the Fed, is said to have driven this step-change in activity. The reticence of commercial banks to extend finance, despite the favourable interest rate and liquidity environment, is a contributing factor: –

Source: Refinitiv, FT

The Covid pandemic has accelerated many of the economic and financial market trends which have been in train since the end of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Lower interest rates, more quantitative easing, further share buy-backs and greater debt issuance – by borrowers’ individual, corporate and national – look set to continue.

A global economic depression is looming, yet the price of many assets continues to rise. In a similar manner to the Tech bubble of the late 1990’s, today’s valuations rely more on the willing suspension of disbelief than on any sober assessment of earnings potential. The US stock market has outperformed partly due to the high proportion of technology stocks, as the chart below (from May) shows: –

Source: FactSet, Goldman Sachs

The magnitude of this fiscal and monetary response has already reached far beyond the United States. The table below shows those national stock markets with a positive year to date performance exceeding 5%: –

Source: Trading Economics, Local Stock Exchanges

I have deliberately excluded the Nasdaq 100 which is currently up more than 57%. Other countries will catch up. The US$ has weakened, since February, on a trade weighted basis: –

Source: BIS, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

In a competitive race to the bottom, other central banks (and their governments) will expand monetary (and fiscal) policy to stop their currencies appreciating too fast.

Global bond yield convergence will continue, stock market strength will endure. Inflation will creep into consumer prices gradually and the central banks will turn a blind eye until it is too late. The world economy may be on its knees but, in general, asset prices will continue to reach for the stars.

Macro Letter – No 131 – 21-08-2020

When does a recession become a depression?

There is a tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.

William Shakespeare (Julius Caesar)

When your neighbour loses their job, it’s a recession.

When you lose your job, that’s a depression!

Harry S. Truman (33rd President of the Unites States)

The common knowledge definition above is grim and highly specific, but its banality serves to highlight the fact that the recession/depression question is not that simple to answer. Back in 2007 The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco – What is the difference between a recession and a depression? – attempted to reach a conclusion. They embraced the NBER definition of a recession: –

A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. A recession begins just after the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends as the economy reaches its trough. Between trough and peak, the economy is in an expansion. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief and they have been rare in recent decades.

And turned to Gregory Mankiw to distinguish between the two states of economic contraction: –

There are repeated periods during which real GDP falls, the most dramatic instance being the early 1930s. Such periods are called recessions if they are mild and depressions if they are more severe.

Despite the Federal Reserve’s valiant efforts, the simpler and more commonly accepted definition of a recession is a consecutive two quarters of decline in GDP. When it comes to depressions, however, there is little consensus; the two most common descriptions are: –

Whilst the two definitions are not mutually exclusive, they are broadly different. I believe the difference between a recession and a depression is more nuanced. A recession is a natural part of the business (or perhaps we should say credit) cycle, a depression, by contrast, involves the physical destruction of the economy – businesses are irreparably broken, employment opportunities terminally destroyed, investment has to be totally written off.

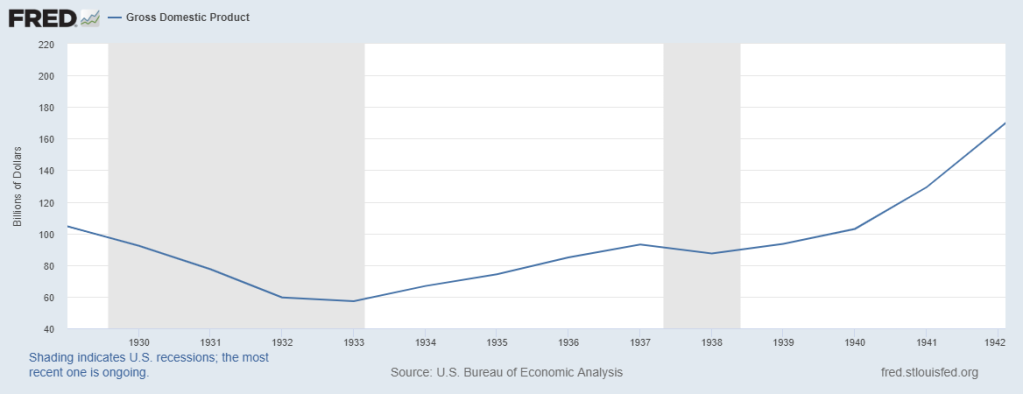

An alternative approach is to examine previous great depressions. Alas, this method proves equally inconsistent, for example the Great Depression of the 1930’s is generally considered to have lasted from 1929 to 1941 and yet, as the chart below reveals, there were only two distinct periods of declining GDP growth between 1930 and 1933 and again between 1937 and 1938: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Notwithstanding my more prosaic definition above, I favour the two year plus definition over that of a sharp decline in GDP. A recession hurts some parts of an economy, a depression is more widespread.

Another factor often associated with recessions and depressions is a rise in the rate of unemployment. Historically, rising unemployment has preceded the onset of recessions and only once recessions have become protracted have they been dubbed depressions.

A further differentiator relates to the absolute level of inflation. In general, as inflation rises, central banks respond by raising short-term interest rates. This helps to cool overheating economies, however, if they tighten too aggressively they may prompt a recession as the credit cycle is forced into a sharp contraction. By contrast a depression is often accompanied by an absolute fall in the price level, caused by an excessive overhang of domestic or corporate debt.

As an investor, why does a depression definition matter? Because financial markets are forward looking. If investors believe the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic will be ‘V’ Shaped, then, even a 20% decline in GDP, together with zero interest rates, price support for government bonds and a fiscal expansion on a scale not witnessed since the ‘New Deal’ of FDR, will rapidly translate inot a sharply rising stock market. If, by contrast, it becomes clear that a tsunami of creative destruction is sweeping away entire industries, then even the most lavish of New New Deals may be insufficient to hold back the tide of stock liquidation as market participates rush to the safety of cash.

So far the official policy response has been sufficient to convince investors that a depression will be avoided. Scratch the surface of the S&P 500, however, and a rather different picture appears. The chart below shows market performance up to the end of May. The same five technology stocks have continued to drive S&P 500 index performance since then: –

Source: FactSet, Goldman Sachs

Technology has been the top performing sector. One argument for such elevated valuations rests on the premise that the pandemic has accelerated a wide range of technology trends bringing with it the potential for much swifter profits. In finance parlance, the net present value of future technology cash-flows has been brought forward by, some analysts suggest, several years. No wonder, they argue, that these stocks have broken to new all-time highs: and will continue, higher.

Since May, the broader stock market has hung of tech coattails (at the time of writing – 19-8-2020 -the MSCI World Index is up 1.73% YTD). For the present, hope triumphs over fear, yet vaccines remain many months from being widely available, meanwhile, for the Northern hemisphere, autumn – and fears of a second wave of infections – draws imminently near.

For emerging markets the situation is worse still. As Carmen and Vincent Reinhart, writing in Foreign Affairs – The Pandemic Depression– put it: –

Although dubbed a “global financial crisis,” the downturn that began in 2008 was largely a banking crisis in 11 advanced economies. Supported by double-digit growth in China, high commodity prices, and lean balance sheets, emerging markets proved quite resilient to the turmoil of the last global crisis. The current economic slowdown is different. The shared nature of this shock—the novel coronavirus does not respect national borders—has put a larger proportion of the global community in recession than at any other time since the Great Depression. As a result, the recovery will not be as robust or rapid as the downturn. And ultimately, the fiscal and monetary policies used to combat the contraction will mitigate, rather than eliminate, the economic losses, leaving an extended stretch of time before the global economy claws back to where it was at the start of 2020.

The World Bank estimates globally more than 60mln people will be pushed into severe poverty. Meanwhile, in developed countries, bankruptcies, which have been postponed by government intervention, may meet their personal epiphanies as fiscal largesse is suddenly withdrawn. Unless the lockdown restrictions are lifted and people feel safe, both medically and financially, to venture out and spend, the destruction of large swathes of developed market economies has simply been deferred.

By next month we will have experienced two quarters of diminished growth – this is a deep recession already. Swathes of the economy have been permanently altered, making a depression highly likely. Millions of workers have been displaced, it will take more than a handful of months for them to be retrained. Without the consumption demand from these erstwhile workers, it will be difficult for new and existing companies to create the growth they need to hire new employees.

Fiscal spending will need to be undertaken on a much larger scale, and for much longer, than has been envisaged so far. In all the major financial crises since 1850, the average time for per capita GDP to recover to the pre-crisis level was eight years. To date it is estimated that the G20 response to the pandemic has amounted to $11trln. Most of these measures have been ‘temporary’ or ‘short-term.’ It is quickly becoming clear, the disruption to employment, business and sectors of the economy will be protracted and, in many cases, permanent, The IMF estimate that for advanced economies the deficit-to-GDP ratio will rise from 3.3% in 2019 to 16.6% this year. For emerging economies, where the capacity for fiscal expansion is more limited, the ratio is expected to swell from 4.9% last year to 10.6% in 2020. Whilst for advanced economies the cost of borrowing has remained low in emerging markets financing costs have risen. The burden of fiscal stimulus will inevitably fall most heavily upon the treasuries of the advanced economies.

Conclusion

As Sir Winston Churchill once said: –

Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

In the aging societies of the West (and elsewhere) the individual need for income remains key. Developed nation governments are fortunate in their ability to borrow more cheaply than at any time in economic history. Whilst it is at odds with my Austrian, free-market instincts, I am forced to admit that fiscal policy is the least panful weapon available to combat the economic catharsis created by the pandemic. Economically, there will be a heavy price to pay, but the alternative is a dangerous cocktail of political fragmentation and polarisation.

For investors the task of securing steady real income remains challenging. Private debt and asset backed lending, which offers high yield, comes with both default and liquidity risk. The chart below looks at some of the public market options, financial repression is rife across the credit spectrum: –

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

High income stocks might be an alternative but they offer no guarantee, no matter how ‘blue-chip’ the name. An addition to the acceleration in technology trends, growth stocks in general are benefitting from the exceptionally low interest environment, but there will be a greater number of failures because the cost of speculative finance is also at an historical low. Active management has been unfashionable for at least a decade but looking ahead preservation of capital is going to be more important than capturing out-sized gains.

I wrote about value investing back in June in – A Brave New World for Value Investing – concluding that: –

Stock and corporate bond markets have regained much of their composure since late March. Central banks and governments have acted to ameliorate the effects of the global economic slowdown. As the dust begins to settle, the financial markets will adjust to a new environment, one in which value-based stock and bond market analysis will provide an essential aid to navigation.

The geopolitics of trade policy, already a source of tension before the pandemic struck, has been turbo-charged by the simultaneous supply and demand shocks and their impact on global supply chains. Supply chains will shorten and diversify. Robustness rather than efficiency will be the watch-word in the months and years ahead. This sea-change in the functioning of the world economy will not be without cost. It will appear in increased prices or reduced corporate profits. Value-based investment analysis will be the best guide in this brave new world.

I would add an additional strategy to the investment armoury, a momentum overlay. With fiscal and monetary policy continuing to support economies as they transition to the new world order, capital flows will be a powerful arbiter of investment return. Technology stocks may look expensive by most normal metrics but the trend is patently clear. Do not emulate Cnut The Great, but do as Brutus advises in the opening quote, after all, financial market liquidity flows like tide.

At the beginning on January I wrote this article for the AIER. Whilst much has changed, the trends have accelerated.

https://www.aier.org/article/the-dangers-to-prosperity-all-around-us/

Macro Letter – No 130 – 26-06-2020

After the flood – Beyond fiscal and monetary intervention

In my last Macro Letter – A Brave New World for Value Investing – I anticipated the beginning of a new phase for equity investment. In this Letter I look at the existing business and economic trends which have been accelerated by the pandemic, together with the new trends ignited by this sea-change in human behaviour.

In economic terms, the Covid pandemic began with a supply-shock in China as they were forced to lockdown the Wuhan region. This exacerbated strains which had already become evident in trade negotiations between China and the US, but also revealed weaknesses in the global supply chains. A kind of ‘Mexican Wave’ has followed, with a variant on the initial supply-shock occurring in successive countries as the virus spreads from region to region and governments responded with lockdowns.

The supply-shock has gone hand in hand with a global demand-shock. The key difference between this recession and previous crises is the degree to which it has impacted the service sector. According to 2017 data, the service sector represents 65% of global GDP, whilst Industrial/Manufacturing accounts for 25%, Agriculture represents only 3.43%. Over time, Agriculture and Manufacturing has become more increasingly automated, the principle growth sector for employment is Services. The ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Fourth edition states: –

As at 17 May 2020, 20 per cent of the world’s workers lived in countries with required workplace closures for all but essential workers. An additional 69 per cent lived in countries with required workplace closures for some sectors or categories of workers, and a further 5 per cent lived in countries with recommended workplace closures.

The latest ILO estimate for Q2, 2020 indicates a 10.7% decline in working hours – equivalent to 305mln lost jobs worldwide. 60% of these job losses have been in four industries, leisure, retail, education and, perhaps counter-intuitively, healthcare. The knock-on effects have been felt almost everywhere.

Governments and central banks have responded. The chart below shows the rapid expansion in central bank balance sheets: –

Source: Yardeni, Haver Analytics

The Federal Reserve began their latest round of quantitative easing in August 2019, well before the onset of the pandemic. They have added $3.3tlrn in nine months, seeing their balance sheet balloon to $7.1trln.

Around the world, governments have also reacted with vigour; on May 20th the IMF updated their estimate of the global fiscal response to $9trln, of which $8trln has emanated from G20 countries. The geographic breakdown as a percentage of GDP can be seen in the table below: –

Source: IMF

The majority of global stimulus has come from the richer developed nations. Assuming this pattern continues, emerging market equities are likely to lag. The table below ranks a selection of emerging economies by four measures of financial strength, public debt, foreign debt, cost of borrowing and reserve cover: –

Source: The Economist, IMF, JP Morgan, iShares

Overall, whilst the flood may subside, global expenditure should continue to rise as the pandemic sweeps on across the globe. Whilst loan forbearance and forgiveness, together with state guarantees, will help to maintain the solvency of many existing corporations, new spending will be aimed at stimulating employment. Infrastructure projects will be legion.

Impact on Industry Sectors

For investors, the abrupt changes in supply and demand, combined with the impact of the fiscal and monetary response, make navigating today’s stock markets especially challenging. To begin, here is a chart from 2019 showing a breakdown of industry sectors in the US by their contribution to GDP: –

Source: Deloitte, BEA, Haver Analytics

This tells us that finance, insurance and real estate are the largest sector but it fails to tell us which sectors are thriving and which are not: –

Source: Deloitte, BEA, Haver Analytics

Here we see the continued march of digital transformation, but also the ever increasing share of healthcare services in GDP; near to four decades of asset price appreciation has created an asset rich aging cohort in developed economies which, if not healthier then definitely wealthier. Looking ahead, developed nations are better equipped to weather the crisis better than their developing nation peers. Within developed nations, however, smaller businesses, especially those which cannot access capital markets, will fail, whilst larger firms will fare far better. Private Equity funds will also find rich pickings among the plethora of distressed private market opportunities.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, several trends have accelerated, others have been truncated or reversed. Social behaviour has had a negative impact on travel, leisure and retail. Declining demand for travel has damaged a range of industries including airlines, autos, oil and gas. The leisure sector has been hit even harder with hotels, restaurants and bars closed, in many cases forever. The sports industry has been severely undermined. Meanwhile the decline in retail has accelerated into a downward spiral.

Nonetheless, several industries have benefitted. Within retail, online sales have hit new records, grocery sales have ballooned. Healthcare has gone digital, from consulting to dispensing productivity gains have been evident. The home improvements industry has benefitted even as commercial real estate has suffered. Working from home will be a permanent feature for many office workers. Every existing home owner will need to create a permanent office space, every new home buyer will need more space to incorporate an office. Longer, occasional, commutes will lead people to move further from the city. Some workers will move to more clement climes, requiring less energy. Structural changes in where we live and how we live present threats and opportunities in equal measure. For example, every house will require better communications infrastructure, high speed connectivity and broad, broadband will become the norm.

Changes in the delivery of goods (direct to homes rather than to retail outlets) means more inventory will held in out-of-town locations. Inner city retail and commercial property businesses will consolidate as out-of-town commercial thrives. New out-of-town property demand will also emerge from the manufacturing sector. The on-shoring of production was already in train, with robots replacing cheap labour from developing countries, now, concern about the robustness of supply chains, especially for critical manufactures such as pharmaceuticals, will encourage a wave of old industries in developing countries to be reborn. Whereas in retail, larger inventory may become more prevalent, in manufacturing, ‘just-in-time’ delivery and lower transportation costs will compensate for higher fixed production costs.

The energy sector has suffered a medium-term setback, for example, 28% of all US gasoline is consumed in the daily commute. After the lockdown, some commuters will choose to travel alone rather than by public transport, many more will now work permanently from home. Yet whilst gasoline demand falls, demand for diesel, to fuel the home delivery revolution, will rise. Home heating (and cooling) is also set to rise and, with it, demand for heating oil and natural gas. Overall demand may be lower but there will be many investment opportunities.

In healthcare, aside from tele-medicine, which is forecast to capture between one third and half of consultation demand, there is also increased appetite for bio-sensors to measure multiple aspects of health. Hospital consolidation will continue in an attempt to drive efficiency. On-shoring of drug manufacture may well be mandated, online delivery is likely to become the new normal, especially to the elderly and infirm who are advised to shelter-in-place. On-shoring creates domestic jobs, government favour will focus on these companies.

Airlines will be forced to diversify or merge; I envisage a mixture of both strategies. A diversification into car hire, travel insurance and hotels seems likely. Many airlines are national carriers, they possess an implicit government guarantee, their financing costs will remain lower, their low-budget competitors will diminish, fare discounts will become fewer and, thereby, their fortunes may conceivably rebound.

The automobile industry remains in a state of turmoil, but new technology will continue to determine its fortune. If de-urbanisation continues, whilst commuting will decline, there will be an increased demand for individual car ownership, especially electric vehicles. In the fullness of time, the industry will transform again with the adoption of driverless transportation.

Technology will, of course, be ubiquitous. The fortunes of the cybersecurity sector have been ascendant since the crisis began, but even relatively ‘non-tech’ businesses will benefit. Commercial real estate will gain as tech firms seek out ever larger data centres to support their cloud computing needs. The auto industry will benefit from improvements in battery storage and charging times. This will also change the economics of electricity for homes and factories. Green energy will come of age.

Tourism will recover, the human race has not lost the desire to travel. In Europe tourism is down between 30% and 40% – it accounts for 10% of GDP. The rebound will be gradual but the travellers will return. More consumers will buy on-line.

Banking and finance will evolve to meet the challenges and needs of the industrial and services sector. Certain trends will continue, bricks and mortar will give way to on-line solutions, branch networks will consolidate. With government support, or threat, existing loans will be extended, new loans made. As household savings rise, new credit will be granted to new and existing entities, few questions will be asked.

Insurance companies will consolidate, once claims are paid, premiums will rise and competition lessened. As with banking more consumers will move on-line.

Employment