Macro Letter – No 48 – 29-01-2016

Central Banks – Ah Aaaaahhh! – Saviours of the Universe?

Copryright: Universal Pictures

- Freight rates have fallen below 2008 levels

- With the oil price below $30 many US producers are unprofitable

- The Fed has tightened but global QE gathers pace

- Chinese stimulus is fighting domestic strong headwinds

Just in case you’re not familiar with it here is a You Tube video of the famous Queen song. It is seven years since the Great Financial Crisis; major stock markets are still relatively close to their highs and major government bond yields remain near historic lows. If another crisis is about to engulf the developed world, do the central banks (CBs) have the means to avert catastrophe once again? Here are some of the factors which may help us to reach a conclusion.

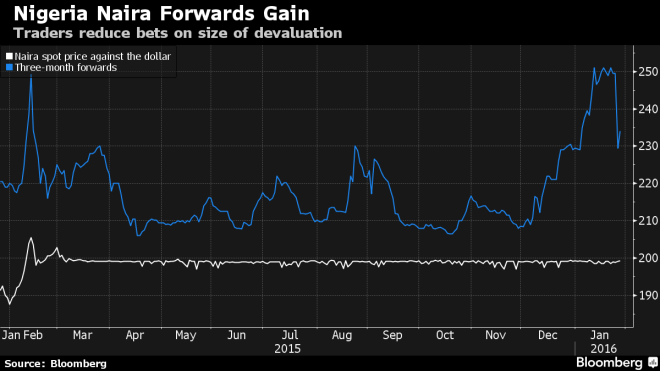

Freight Rates

Last week I was asked to comment of the prospects for commodity prices, especially energy. Setting aside the geo-politics of oil production, I looked at the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) which has been plumbing fresh depths this year – 337 (28/1/16) down from August 2015 highs of 1200. Back in May 2008 it touched 11,440 – only to plummet to 715 by November of the same year. How helpful is the BDI at predicting the direction of the economy? Not very – as this 2009 article from Business Insider – Shipping Rates Are Lousy For Predicting The Economy – points out. Nonetheless, the weakness in freight rates is indicative of an inherent lack of demand for goods. The chart below is from an article published by Zero Hedge at the beginning of January – they quote research from Deutsche Bank.

Source: Zerohedge

A “Perfect Storm Is Coming” Deutsche Warns As Baltic Dry Falls To New Record Low:–

…a “perfect storm” is brewing in the dry bulk industry, as year-end improvements in rates failed to materialize, which indicates a looming surge in bankruptcies.

…The improvement in dry bulk rates we expected into year-end has not materialized.

…we believe a number of dry bulk companies are contemplating asset sales to raise liquidity, lower daily cash burn, and reduce capital commitments. The glut of “for sale” tonnage has negative implications for asset and equity values. More critically, it can easily lead to breaches in loan-to-value covenants at many dry bulk companies, shortening the cash runway and likely necessitating additional dilutive actions.

Dry bulk companies generally have enough cash for the next 1yr or so, but most are not well positioned for another leg down in asset values.

China

The slowing and rebalancing of the Chinese economy may be having a significant impact on global trade flows. Here is a recent article on the subject from Mauldin Economics – China’s Year of the Monkees:-

China isn’t the only reason markets got off to a terrible start this month, but it is definitely a big factor (at least psychologically). Between impractical circuit breakers, weaker economic data, stronger capital controls, and renewed currency confusion, China has investors everywhere scratching their heads.

When we focused on China back in August (see “When China Stopped Acting Chinese”), my best sources said the Chinese economy was on a much better footing than its stock market, which was in utter chaos. While the manufacturing sector was clearly in a slump, the services sector was pulling more than its fair share of the GDP load. Those same sources have new data now, which leads them to quite different conclusions.

…Now, it may well be the case that China’s economy is faltering, but its GDP data is not the best evidence.

…To whom can we turn for reliable data? My go-to source is Leland Miller and company at the China Beige Book.

…China Beige Book started collecting data in 2010. For the entire time since then, the Chinese economy has been in what Leland calls “stable deceleration.” Slowing down, but in an orderly way that has generally avoided anything resembling crisis.

…China Beige Book noticed in mid-2014 that Chinese businesses had changed their behavior. Instead of responding to slower growth by doubling down and building more capacity, they did the rational thing (at least from a Western point of view): they curbed capital investment and hoarded cash. With Beijing still injecting cash that businesses refused to spend, the liquidity that flowed into Chinese stocks produced the massive rally that peaked in mid-2015. It also allowed money to begin to flow offshore in larger amounts. I mean really massively larger amounts.

…Dealing with a Different China

China Beige Book’s fourth-quarter report revealed a rude interruption to the positive “stable deceleration” trend. Their observers in cities all over that vast country reported weakness in every sector of the economy. Capital expenditures dropped sharply; there were signs of price deflation and labor market weakness; and both manufacturing and service activity slowed markedly.

That last point deserves some comment. China experts everywhere tell us the country is transitioning from manufacturing for export to supplying consumer-driven services. So if both manufacturing and service activity are slowing, is that transition still happening?

The answer might be “yes” if manufacturing were decelerating faster than services. For this purpose, relative growth is what counts. Unfortunately, manufacturing is slowing while service activity is not picking up all the slack. That’s not the combination we want to see.

Something else China Beige Book noticed last quarter: both business and consumer loan volume did not grow in response to lower interest rates. That’s an important change, and probably not a good one. It means monetary stimulus from Beijing can’t save the day this time. Leland thinks fiscal stimulus isn’t likely to help, either. Like other governments and their central banks, China is running out of economic ammunition.

Mauldin goes on to discuss the devaluation of the RMB – which I also discussed in my last letter – Is the ascension of the RMB to the SDR basket more than merely symbolic? The RMB has been closely pegged to the US$ since 1978 though with more latitude since 2005, this has meant a steady appreciation in its currency relative to many of its emerging market trading partners. Now, as China begins to move towards full convertibility, the RMB will begin to float more freely. Here is a five year chart of the Indian Rupee and the CNY vs the US$:-

Source: Yahoo finance

The Chinese currency could sink significantly should their government deem it necessary, however, expectations of a collapse of growth in China may be premature as this article from the Peterson Institute – The Price of Oil, China, and Stock Market Herding – indicates:-

A collapse of growth in China would indeed be a world changing event. But there is just no evidence of such a collapse. At most there is suggestive evidence of a mild slowdown, and even that is far from certain. The mechanical effects of such a mild decrease on the US economy should, by all accounts, and all the models we have, be limited. Trade channels are limited (US exports to China represent less than 2 percent of GDP), and so are financial linkages. The main effect of a slowdown in China would be through lower commodity prices, which should help rather than hurt the United States.

Peterson go on to suggest:-

Maybe we should not believe the market commentaries. Maybe it was neither oil nor China. Maybe what we are seeing is a delayed reaction to the slowdown in the world economy, a slowdown that has now gone on for a few years. While there has been no significant news in the last two weeks, maybe markets are only realizing that growth in emerging markets will be lower for a long time, that growth in advanced economies will be unexciting. Maybe…

I think the explanation is largely elsewhere. I believe that to a large extent, herding is at play. If other investors sell, it must be because they know something you do not know. Thus, you should sell, and you do, and so down go stock prices. Why now? Perhaps because we have entered a period of higher uncertainty. The world economy, at the start of 2016, is a genuinely confusing place. Political uncertainty at home and geopolitical uncertainty abroad are both high. The Fed has entered a new regime. The ability of the Chinese government to control its economy is in question. In that environment, in the stock market just as in the presidential election campaign, it is easier for the bears to win the argument, for stock markets to fall, and, on the political front, for fearmongers to gain popularity.

They are honest enough to admit that economics won’t provide the answers.

Energy Prices

The June 2015 BP – Statistical Review of World Energy – made the following comments:-

Global primary energy consumption increased by just 0.9% in 2014, a marked deceleration over 2013 (+2.0%) and well below the 10-year average of 2.1%. Growth in 2014 slowed for every fuel other than nuclear power, which was also the only fuel to grow at an above-average rate. Growth was significantly below the 10-year average for Asia Pacific, Europe & Eurasia, and South & Central America. Oil remained the world’s leading fuel, with 32.6% of global energy consumption, but lost market share for the fifteenth consecutive year.

Although emerging economies continued to dominate the growth in global energy consumption, growth in these countries (+2.4%) was well below its 10-year average of 4.2%. China (+2.6%) and India (+7.1%) recorded the largest national increments to global energy consumption. OECD consumption fell by 0.9%, which was a larger fall than the recent historical average. A second consecutive year of robust US growth (+1.2%) was more than offset by declines in energy consumption in the EU (-3.9%) and Japan (-3.0%). The fall in EU energy consumption was the second-largest percentage decline on record (exceeded only in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2009).

The FT – The world energy outlook in five charts – looked at five charts from the IEA World Energy Outlook – November 2015:-

Source: IEA

With 315m of its population expected to live in urban areas by 2040, and its manufacturing base expanding, India is forecast to account for quarter of global energy demand growth by 2040, up from about 6 per cent currently.

Source: IEA

Oil demand in India is expected to increase by more than in any other country to about 10m barrels per day (bpd). The country is also forecast to become the world’s largest coal importer in five years. But India is also expected to rely on solar and wind power to have a 40 per cent share of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030.

Source: IEA

China’s total energy demand is set to nearly double that of the US by 2040. But a structural shift in the Asian country away from investment-led growth to domestic-demand based economy will “mean that 85 per cent less energy is required to generate each unit of future economic growth than was the case in the past 25 years.”

Source: IEA

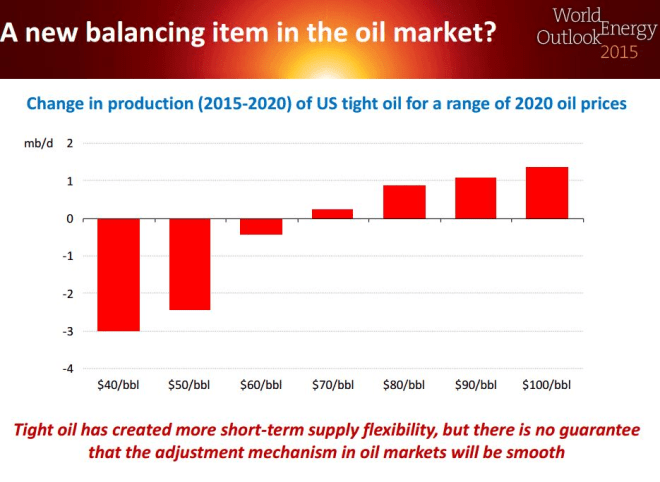

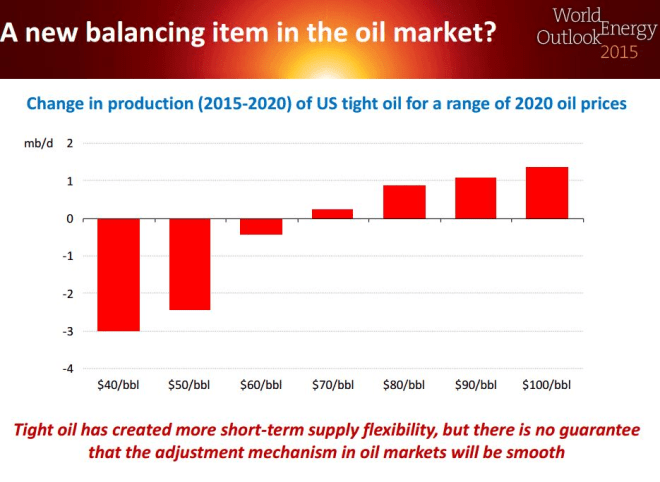

US shale oil production is expected to “stumble” in the short term, but rise as oil price recovers. However the IEA does not expect crude oil to reach $80 a barrel until 2020, under its “central scenario”. The chart shows that if prices out to 2020 remain under $60 per barrel, production will decline sharply.

Source: IEA

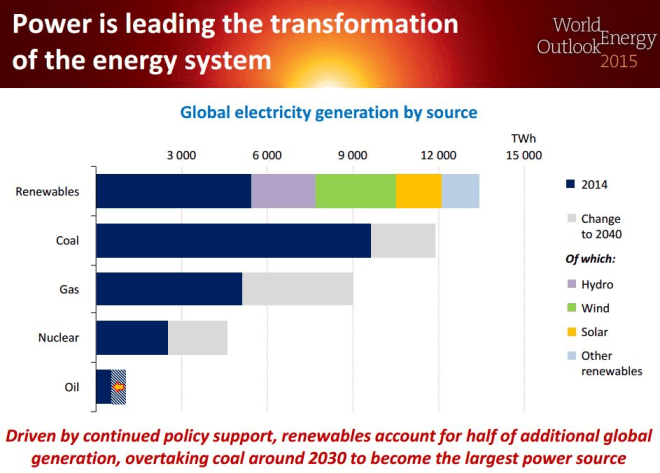

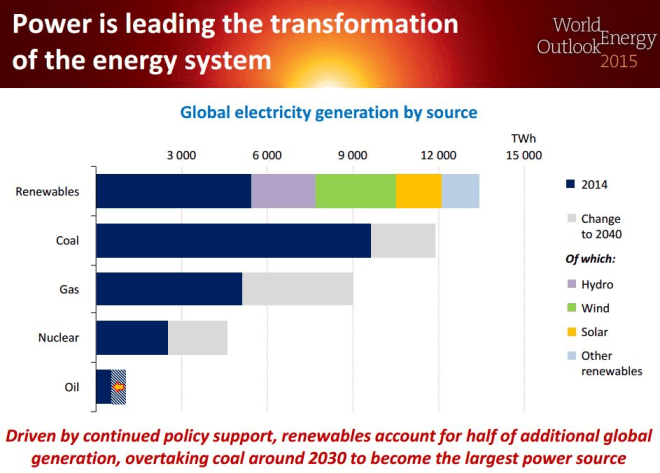

Renewables are set to overtake coal to become the largest source of power by 2030. The share of coal in the production of electricity will fall from 41 per cent to 30 per cent by 2040, while renewables will account for more than half the increase in electricity generation by then.

The cost of solar energy continues to fall and is now set to “eclipse” natural gas, as this article from Seeking Alpha by Siddharth Dalal – Falling Solar Costs: End Of Natural Gas Is Near? Explains:-

A gas turbine power plant uses 11,371 Btu/kWh. The current price utilities are paying per Btu of natural gas are $3.23/1000 cubic feet. 1000 cubic feet of natural gas have 1,020,000 BTUs. So $3.23 for 90kWh. That translates to 3.59c/kWh in fuel costs alone.

A combined cycle power plant uses 7667 Btu/kWh, which translates to 2.42c/kWh.

Adding in operating and maintenance costs, we get 4.11c/kWh for gas turbines and 3.3c/kWh for combined cycle power plants. This still doesn’t include any construction costs.

…The average solar PPA is likely to go under 4c/kWh next year. Note that this is the total cost that the utility pays and includes all costs.

And the trend puts total solar PPA costs under gas turbine fuel costs and competitive with combined cycle plant total operating costs next year.

At this point it becomes a no brainer for a utility to buy cheap solar PPAs compared to building their own gas power plants.

The only problem here is that gas plants are dispatchable, while solar is not. This is a problem that is easily solved by batteries. So utilities would be better served by spending capex on batteries as opposed to any kind of gas plant, especially anything for peak generation.

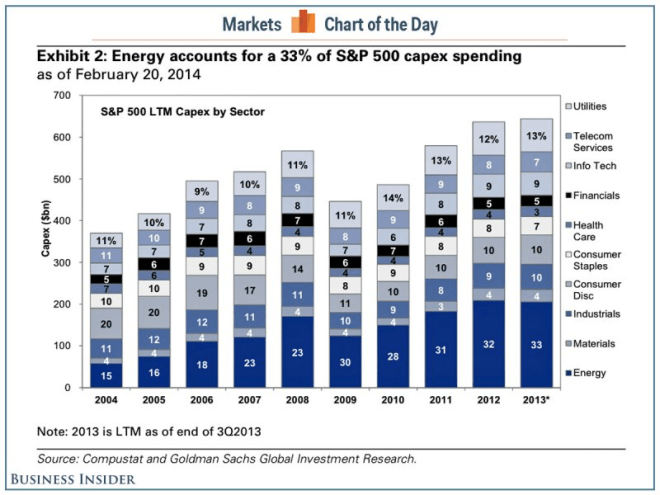

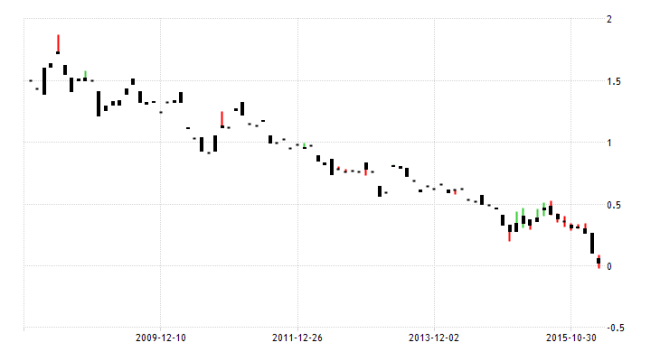

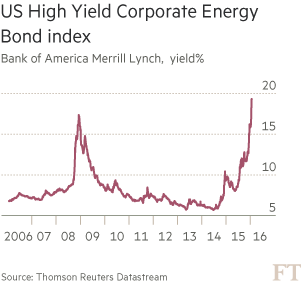

The influence of the oil price, whilst diminishing, still dominates. In the near term the importance of the oil price on financial market prices will relate to the breakeven cost of production for companies involved in oil exploration. Oil companies have shelved more than $400bln of planned investment since 2014. The FT – US junk-rated energy debt hits two-decade low – takes up the story:-

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, FT

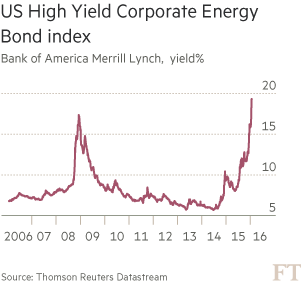

The average high-yield energy bond has slid to just 56 cents on the dollar, below levels touched during the financial crisis in 2008-09, as investors brace for a wave of bankruptcies.

…The US shale revolution which sent the country’s oil production soaring from 2009 to 2015 was led by small and midsized companies that typically borrowed to finance their growth. They sold $241bn worth of bonds during 2007-15 and many are now struggling under the debts they took on.

Very few US shale oil developments can be profitable with crude at about $30 a barrel, industry executives and advisers say. Production costs in shale have fallen as much as 40 per cent, but that has not been enough to keep pace with the decline in oil prices.

…On Friday, Moody’s placed 120 oil and gas companies on review for downgrade, including 69 in the US.

…The yield on the Bank of America Merrill Lynch US energy high-yield index has climbed to the highest level since the index was created, rising to 19.3 per cent last week, surpassing the 17 per cent peak hit in late 2008.

More than half of junk-rated energy groups in the US have fallen into distress territory, where bond yields rise more than 1,000 basis points above their benchmark Treasury counterpart, according to S&P.

All other things equal, the price of oil is unlikely to rally much from these levels, but, outside the US, geo-political risks exist which may create an upward bias. Many Middle Eastern countries have made assumptions about the oil price in their estimates of tax receipts. Saudi Arabia has responded to lower revenues by radical cuts in public spending and privatisations – including a proposed IPO for Saudi Aramco. As The Guardian – Saudi Aramco privatisation plans shock oil sector – explains, it will certainly be difficult to value – market capitalisation estimates range from $1trln to $10trln.

Outright energy company bankruptcies are likely to be relatively subdued, unless interest rates rise dramatically – these companies locked in extremely attractive borrowing rates and their bankers will prefer to renegotiate payment schedules rather than write off the loans completely. New issuance, however, will be a rare phenomenon.

Technology

“We don’t want technology simply because it’s dazzling. We want it, create it and support it because it improves people’s lives.”

These words were uttered by Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, at Davos last week. The commodity markets have been dealing with technology since the rise of Sumer. The Manhattan Institutes – SHALE 2.0 Technology and the Coming Big-Data Revolution in America’s Shale Oil Fields highlights some examples which go a long way to explaining the downward trajectory in oil prices over the last 18 months – emphasis is mine:-

John Shaw, chair of Harvard’s Earth and Planetary Sciences Department, recently observed: “It’s fair to say we’re not at the end of this [shale] era, we’re at the very beginning.” He is precisely correct. In recent years, the technology deployed in America’s shale fields has advanced more rapidly than in any other segment of the energy industry. Shale 2.0 promises to ultimately yield break-even costs of $5–$20 per barrel—in the same range as Saudi Arabia’s vaunted low-cost fields.

…Compared with 1986—the last time the world was oversupplied with oil—there are now 2 billion more people living on earth, the world economy is $30 trillion bigger, and 30 million more barrels of oil are consumed daily. The current 33 billion-barrel annual global appetite for crude will undoubtedly rise in coming decades. Considering that fluctuations in supply of 1–2 MMbd can swing global oil prices, the infusion of 4 MMbd from U.S. shale did to petroleum prices precisely what would be expected in cyclical markets with huge underlying productive capacity.

Shipbuilding has also benefitted from technological advances in a variety of areas, not just fuel efficiency. This article (please excuse the author’s English) from Marine Insight – 7 Technologies That Can Change The Future of Shipbuilding – highlights several, I’ve chosen five:-

3-D Printing Technology:…Recently, NSWC Carderock made a fabricated model of the hospital ship USNS Comfort (T-AH 20) using its 3-D printer, first uploading CAD drawings of ship model in it. Further developments in this process can lead the industry to use this technique to build complex geometries of ship like bulbous bow easily. The prospect of using 3-D printers to seek quick replacement of ship’s part for repairing purpose is also being investigated. The Economist claims use this technology to be the “Third Industrial Revolution“.

Shipbuilding Robotics: Recent trends suggest that the shipbuilding industry is recognizing robotics as a driver of efficiency along with a method to prevent workers from doing dangerous tasks such as welding. The shortage of skilled labour is also one of the reasons to look upon robotics. Robots can carry out welding, blasting, painting, heavy lifting and other tasks in shipyards.

…LNG Fueled engines

…In the LNG engines, CO2 emission is reduced by 20-25% as compared to diesel engines, NOX emissions are cut by almost 92%, while SOX and particulates emissions are almost completely eliminated.

…Besides being an environmental friendly fuel, LNG is also cheaper than diesel, which helps the ship to save significant amount of money over time.

…Solar & Wind Powered Ships:

…The world’s largest solar powered ship named ‘Turanor’ is a 100 metric ton catamaran which motored around the world without using any fuel and is currently being used as a research vessel. Though exclusive solar or wind powered ships look commercially and practically not viable today, they can’t be ruled out of future use with more technical advancements.

Recently, many technologies have come which support the big ships to reduce fuel consumption by utilizing solar panels or rigid sails. A device named Energy Sail (patent pending) has been developed by Eco Marine Power will help the ships to extract power from wind and sun so as to reduce fuel costs and emission of greenhouse gases. It is exclusively designed for shipping and can be fitted to wide variety of vessels from oil carrier to patrol ships.

Buckypaper: Buckypaper is a thin sheet made up of carbon nanotubes (CNT). Each CNT is 50,000 thinner than human air. Comparing with the conventional shipbuilding material (i.e. steel), buckypaper is 1/10th the weight of steel but potentially 500 times stronger in strength and 2 times harder than diamond when its sheets are compiled to form a composite. The vessel built from this lighter material would require less fuel, hence increasing energy efficiency. It is corrosion resistant and flame retardant which could prevent fire on ships. A research has already been initiated for the use of buckypaper as a construction material of a future aeroplane. So, a similar trend can’t be ruled out in case of shipbuilding.

Shipping has always been a cyclical business, driven by global demand for freight on the one hand and improvements in technology on the other. The cost of production continues to fall, old inventory rapidly becomes uncompetitive and obsolete. The other factor effecting the cycle is the cost of finance; this is true also of energy exploration and development. Which brings us to the actions of the CBs.

The central role of the central banks

Had $100 per barrel oil encouraged a rise in consumer price inflation in the major economies, it might have been appropriate for their CBs to raise interest rates, however, high levels of debt kept inflation subdued. The “unintended consequences” or, perhaps we should say “collateral damage” of allowing interest rates to remain unrealistically low, is overinvestment. The BIS – Self-oriented monetary policy, global financial markets and excess volatility of international capital flows – looks at the effect developed country CB policy – specifically the Federal Reserve – has had on emerging markets:-

A major policy question arising from these events is whether US monetary policy imparts a global ‘externality’ through spillover effects on world capital flows, credit growth and asset prices. Many policy makers in emerging markets (e.g. Rajan, 2014) have argued that the US Federal Reserve should adjust its monetary policy decisions to take account of the excess sensitivity of international capital flows to US policy. This criticism questions the view that a ‘self-oriented’ monetary policy based on inflation targeting principles represents an efficient mechanism for the world monetary system (e.g. Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2002), without the need for any cross-country coordination of policies.

…Our results indicate that the simple prescriptions about the benefits of flexible exchange rates and inflation targeting are very unlikely to hold in a global financial environment dominated by the currency and policy of a large financial centre, such as the current situation with the US dollar and US monetary policy. Our preliminary analysis does suggest however that an optimal monetary policy can substantially improve the workings of the international system, even in the absence of direct intervention in capital markets through macro-prudential policies or capital controls. Moreover, under the specific assumptions maintained in this paper, this outcome can still be consistent with national independence in policy, or in other words, a system of ‘self-oriented’ monetary policy making.

Whether CBs should consider the international implications of their actions is not a new subject, but this Cobden Centre article by Alisdair Macleod – Why the Fed Will Never Succeed – suggests that the Fed should be mandated to accept a broader role:-

That the Fed thinks it is only responsible to the American people for its actions when they affect all nations is an abrogation of its duty as issuer of the reserve currency to the rest of the world, and it is therefore not surprising that the new kids on the block, such as China, Russia and their Asian friends, are laying plans to gain independence from the dollar-dominated system. The absence of comment from other central banks in the advanced nations on this important subject should also worry us, because they appear to be acting as mute supporters for the Fed’s group-think.

This is the context in which we need to clarify the effects of the Fed’s monetary policy. The fundamental question is actually far broader than whether or not the Fed should be raising rates: rather, should the Fed be managing interest rates at all? Before we can answer this question, we have to understand the relationship between credit and the business cycle.

There are two types of economic activity, one that correctly anticipates consumer demand and is successful, and one that fails to do so. In free markets the failures are closed down quickly, and the scarce economic resources tied up in them are redeployed towards more successful activities. A sound-money economy quickly eliminates business errors, so this self-cleansing action ensures there is no build-up of malinvestments and the associated debt that goes with it.

When there is stimulus from monetary inflation, it is inevitable that the strict discipline of genuine profitability that should guide all commercial enterprises takes a back seat. Easy money and interest rates lowered to stimulate demand distort perceptions of risk, over-values financial assets, and encourages businesses to take on projects that are not genuinely profitable. Furthermore, the owners of failing businesses find it possible to run up more debts, rather than face commercial reality. The result is a growing accumulation of malinvestments whose liquidation is deferred into the future.

Macleod goes on to discuss the Cantillon effect, at what point we are in the Credit Cycle and why the Fed decided to raise rates now:-

We must put ourselves in the Fed’s shoes to try to understand why it has raised rates. It has seen the official unemployment rate decline for a prolonged period, and more recently energy and commodity prices have fallen sharply. Assuming it believes government unemployment figures, as well as the GDP and its deflator, the Fed is likely to think the economy has at least stabilised and is fundamentally healthy. That being the case, it will take the view the business cycle has turned. Note, business cycle, not credit-driven business cycle: the Fed doesn’t accept monetary policy is responsible for cyclical phenomena. Therefore, demand for energy and commodities is expected to increase on a one or two-year view, so inflation can be expected to pick up towards the 2% target, particularly when the falls in commodity and energy prices drop out of the back-end of the inflation numbers. Note again, inflation is thought to be a demand-for-goods phenomenon, not a monetary phenomenon, though according to the Fed, monetary policy can be used to stimulate or control it.

Unfortunately, the evidence from multiple surveys is that after nine years since the Lehman crisis the state of the economy remains suppressed while debt has continued to increase, so this cycle is not in the normal pattern. It is clear from the evidence that the American economy, in common with the European and Japanese, is overburdened by the accumulation of malinvestments and associated debt. Furthermore, nine years of wealth attrition through monetary inflation (as described above) has reduced the purchasing power of the average consumer’s earnings significantly in real terms. So instead of a phase of sustainable growth, it is likely America has arrived at a point where the economy can no longer bear the depredations of further “monetary stimulus”. It is also increasingly clear that a relatively small rise in the general interest rate level will bring on the next crisis.

So what will the Fed – and, for that matter, other major CBs – do? I look back to the crisis of 2008/2009 – one of the unique aspects of this period was the coordinated action of the big five: the Fed, ECB, BoJ, BoE and SNB. In 1987 the Fed was the “saviour of the universe”. Their actions became so transparent in the years that followed, that the phase “Greenspan Put” was coined to describe the way the Fed saved stock market investors and corporate creditors. CEPR – Deleveraging? What deleveraging? which I have quoted from in previous letters, is an excellent introduction to the unintended consequences of CB largesse.

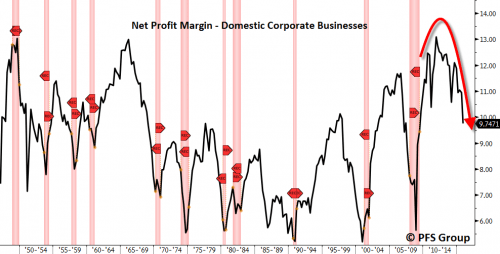

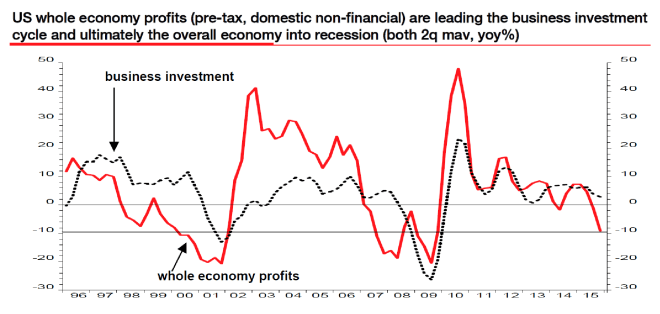

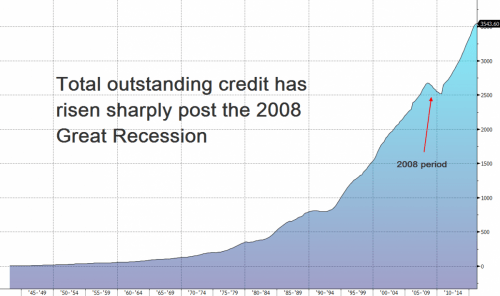

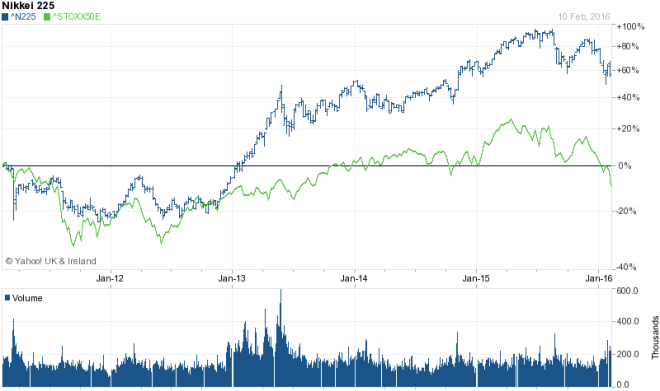

Since 2009 economic growth has remained sluggish; this has occurred despite historically low interest rates – it’s not unreasonable to surmise that the massive overhang of debt, globally, is weighing on both demand pull inflation and economic growth. Stock buy-backs have been rife and the long inverted relationship between dividend yields and government bond yields has reversed. Paying higher dividends may be consistent with diversifying a company’s investor base but buying back stock suggests a lack of imagination by the “C” Suite. Or perhaps these executives are uncomfortable investing when interest rates are artificially low.

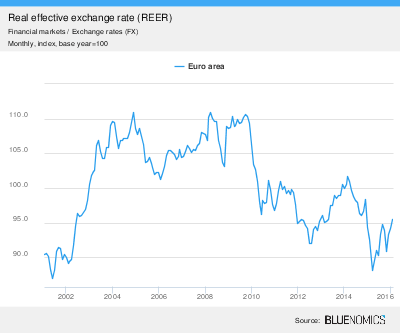

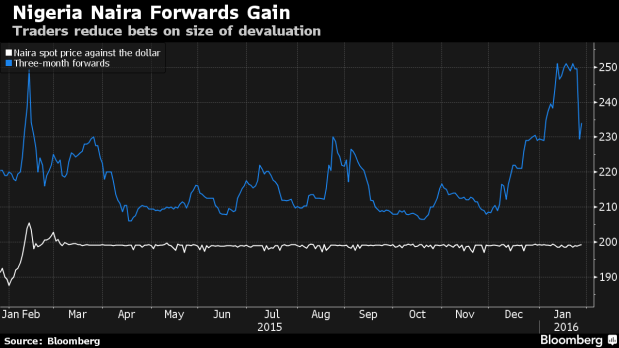

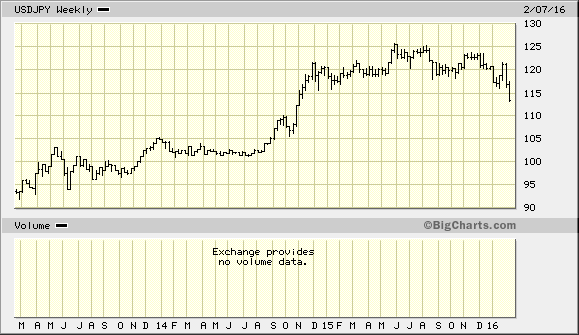

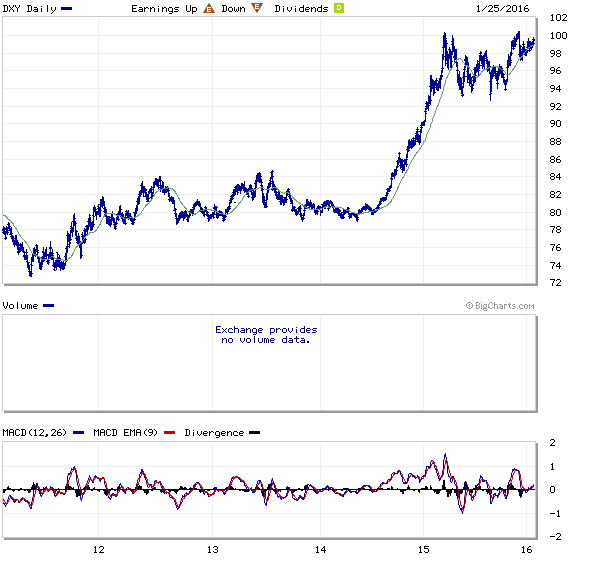

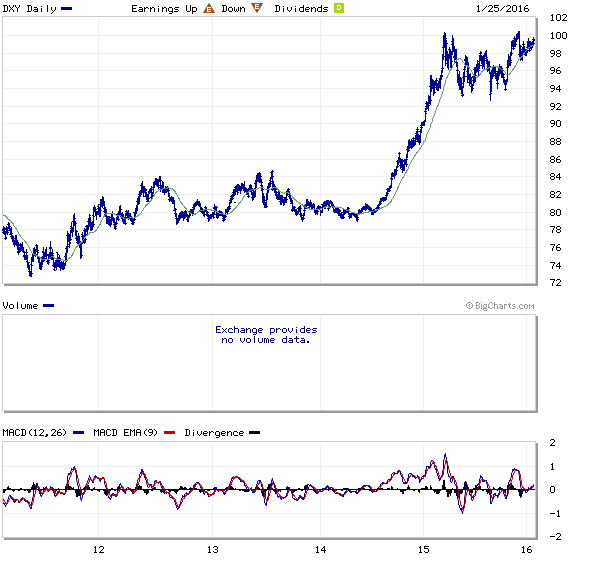

I believe the vast majority of the rise in stock markets since 2009 has been the result of CB policy, therefore the Fed rate increase is highly significant. The actions of the other CBs – and here I would include the PBoC alongside the big five – is also of significant importance. Whilst the Fed has tightened the ECB and the PBoC continue to ease. The Fed appears determined to raise rates again, but the other CBs are likely to neutralise the overall effect. Currency markets will take the majority of the strain, as they have been for the last couple of years.

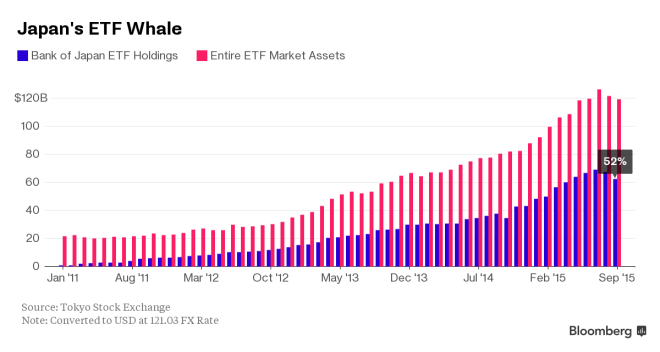

A collapse in equity markets will puncture confidence and this will undermine growth prospects globally. Whilst some of the malinvestments of the last seven years will be unwound, I expect CBs to provide further support. The BoJ is currently the only CB with an overt policy of “qualitative easing” – by which I mean the purchasing of common stock – I fully expect the other CBs to follow to adopt a similar approach. For some radical ideas on this subject this paper by Professor Roger Farmer – Qualitative Easing: How it Works and Why it Matters – which was presented at the St Louis Federal Reserve conference in 2012 – makes interesting reading.

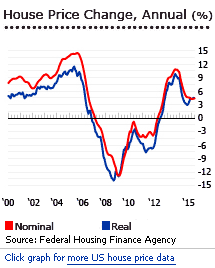

Investment opportunities

In comparison to Europe– especially Germany – the US economy is relatively immune to the weakness of China. This is already being reflected in both the currency and stocks markets. The trend is likely to continue. In the emerging market arena Brazil still looks sickly and the plummeting price of oil isn’t helping, meanwhile India should be a beneficiary of cheaper oil. Some High yield non-energy bonds are likely to be “tarred” (pardon the pun) with the energy brush. Meanwhile, from an international perspective the US$ remains robust even as the US$ Index approaches resistance at 100.

Source: Marketwatch