Macro Letter – No 54 – 06-05-2016

Brexit, Grexit and the rise and fall and rise again of the Euro

- Should the UK leave the EU, Euro volatility will follow

- If the UK remains, the Euro experiment might still be scuppered

- The problems of the EU periphery are not solved by the UK remaining

Whilst the majority of articles between now and the 23rd June will focus on whether the UK will leave or remain in the EU and what this might mean, I want to consider the impact Brexit is likely to have on the long-run fortunes of the Euro.

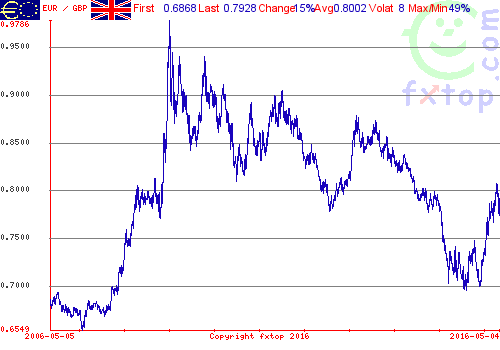

Since December 2008 the EURGBP has fallen from 0.979 to a low of 0.694 in July 2015. Since the end of last year concern, about the outcome of a UK referendum on whether to remain or leave the EU, has seen the EUR strengthen to 0.810 – just over a 38.2% retracement. The UK economy has already begun to show signs of economic slowdown due to uncertainty. A vote to leave is likely to have a negative impact on the GBP, initially, if for no other reason than the continuation of uncertainty; neither the government nor the opposition has presented a road map for exit should the electorate decide to leave. In the event of a UK departure I could envisage a move back to 0.865 or even 0.971:-

Source: fxtop.com

I believe the impact on the UK economy of Brexit would therefore be a substantial weakening of the GBP, a rise in UK inflation and an initial slowing of economic growth. Our exports would rise and our imports would decline, improving our trade balance. Those European countries for whom the UK is their largest export market would suffer.

The cost of the UK leaving the EU would not stop there. The UK is the second largest member of the union. In terms of the economic and political strength of the EU, Britain’s inclusion is significant. By leaving the Schengen Agreement area we would impose higher costs on the remaining members, potentially hastening its interruption or demise. The ECIPE Five Freedom Project – The Cost of Non-Schengen for the Single Market published this week, provides an alarming vision of what that cost to EU growth might be:-

If Schengen would be suspended for the two-year period or even in full, trade and economic growth in the EU could be severely damaged. The Schengen Agreement is not just a symbol of European integration, it creates real economic value by facilitating cross-border exchange. Obviously, the Schengen Agreement promotes the free movement of people, but that is not all. It also boosts the flow of goods, services and capital across borders.

…In 2015 intra-EU trade in goods made up for approximately 60% of the EU’s overall trade.

…The Bertelsmann Stiftung estimated the impact of reintroduced border controls on the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP). Border checks which stop and control trucks cause time delays which increase transport costs and lead to higher product prices. According to their results these higher product prices can cause a yearly reduction in GDP growth of 0.04 percentage points compared to intra-EU trade with open borders. Furthermore, the study argues that the time delays at the border would make just-in-time production and decentralized production more difficult for European firms. As a result, production costs for intra-European value chains would increase and the price competitiveness of European producers would decrease. This could affect location and investment decisions by foreign firms.

A recent Ifo study finds that for EU member states the removal of border controls leads to an increase of 3.8% in goods trade or a cost saving equivalent to a tariff reduction of 0.7 percentage points for every internal border which a good needs to cross. As a result, countries which are at the periphery of the Schengen Area benefit more from the Agreement because their costs savings are greater if goods have to cross several borders until they reach their markets.

Such an integral pillar of EU membership as the Schengen Agreement may not be suspended, but concerns about the indebtedness of some of the more profligate peripheral countries is likely to return to the fore by the summer. As reported earlier this week by Reuters – Greek bank stocks could rise 90 percent on bailout cash deal: Morgan Stanley:-

…upgraded Greek banks to “overweight” saying current valuations did not reflect the compression in bond yield spreads that would follow a deal with Athens’ lenders and took an overly pessimistic view on the banks’ return on equity targets.

The Economist – The threat of Grexit never really went away sees it rather differently: –

Greece badly needs the next dollop of the €86 billion ($99 billion) bail-out creditors promised it last summer, in exchange for promises of austerity and reform. But it will not get the money until the creditors complete a review of its progress, which has been dragging on since November. The government has scraped together enough cash (by raiding independent public agencies) to pay salaries and pensions in May, perhaps even in June. But by July 20th, when a bond worth more than €2 billion matures, the country once again faces default and perhaps a forced exit from the euro zone. The threat of Grexit is not exactly back; it never really went away.

Meanwhile the creation of the “Atlas Fund” which will purchase non-performing loans of Italian banks which are in distress, appears to have averted the, potentially fatal, run on the Italian banking system which was developing earlier this year. Bruegel – Italy’s Atlas bank bailout fund: the shareholder of last resort takes up the story:-

Italy’s new bank fund Atlas might be what is needed in the short run, but in the longer term the fund will increase systemic risk. What ultimately matters is how this initiative will affect the quality of bank governance, a key issue for the future resilience of the system.

…The Atlas fund has a heavy task, although probably not as heavy as that of its mythological namesake. In the short run, it might be what most commentators have described: an imperfect but needed second-best way to avoid bail-in and resolution, matching repeated calls from the Bank of Italy for a revision of the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) framework after Italy negotiated and approved it.

However, by acting as a bank shareholder of last resort the fund increases systemic risk in the longer term, weakening the stronger banks and involving a publicly controlled institution whose main source of funding is postal savings into a rather risky venture.

While it’s unclear whether the aim is to keep foreign capital out of the Italian banking system, what ultimately matters is how this initiative will affect (or avoid affecting) the quality of bank governance, a key issue for the future resilience of the system. Regardless of whether we think that keeping weak banks alive at all costs is a good idea, the idea of such a shareholder of last resort appears at odds with the aim of making progress towards a solid European Banking Union.

Conclusion

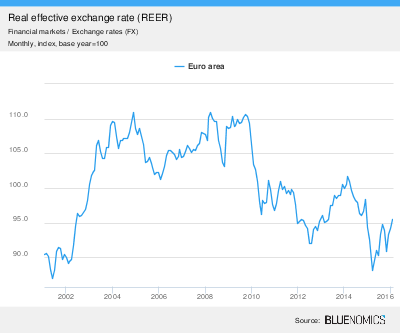

The implications of a UK exit from the EU would, initially, lead to a strengthening EURGBP, although not necessarily EURUSD. This will be followed by a period of increased uncertainty about the survival of the Eurozone (EZ) during which the EUR will decline against its main trading partners. The chart below shows the Euro effective Exchange rate over the last 15 years:-

Source: Bluenomics, Eurostat

Once the first country leaves the EZ, sentiment will change once more. Investors will realise that the departure of the periphery strengthens the prospects of the currency union for those countries which remain; the EUR will begin to look less like a Drachma and more like a Deutschemark. The 2009 highs on the chart above will be within reach and a long-term trajectory similar to, though less steep than, the path of the CHF could become the norm.

For those who thrive on market volatility, over the next few years, opportunities to trade the EUR will be golden.