Macro Letter – No 97 – 18-05-2018

Robots, employment and the mis-measurement of productivity

- UK productivity – output/hour has risen 1.5% in a decade

- UK unemployment, at 4.2%, is the lowest since April 1975

- UK real-wages have risen by 1.1% per annum over the last four years

- Robots may be coming but it’s not showing up in the data

The subject matter of this Macro Letter is broad, so I shall confine my investigation to the UK. It was, after all, one of the first countries where services became a larger percentage of GDP than manufacturing. The crossover between manufacturing and services is estimated to have happened around 1881. When Napoleon Bonaparte described England as, ‘A nation of shopkeepers,’ his intension may have been derisive, but his observation was prescient. Of course, M. Bonaparte was actually quoting Adam Smith, who first coined the phrase in his magnum opus, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776: now, he really was prescient.

As we stare into the abyss, anticipating the huge percentage of manufacturing – and now, many services – jobs which are expected to be replaced by machines, it behoves us to begin by reviewing the accuracy with which we measure services in general. A recent paper from the Centre for Economic and Business Research does just that for one sub-sector, although it suggests that mis-measurement of economic activity in services, always difficult to define, may be a factor in the poor productivity record of the UK. I have often described Britain as a post-industrial nation but this research, into one of the most vibrant corners of the economy, makes fascinating reading – The True Value of Creative Industries Digital Exports – CIC, CBER – March 2018 – finds, among other things that: –

The UK’s creative industries exports are: –

£46bn in goods and services – 24% higher than the official figure

£31bn of total creative exports are services – 41% higher than the official figure

£21bn of these creative services are digital services – 40% higher than the official figure

The CEBR goes on to point out other weaknesses in current measurements of economic activity: –

…estimated official figures for 2016 highlight that the majority of creative industries sub-sectors are exporting digital services. The IT, software and computer services sector, for example, exports £8.95bn in digital services. However, according to these figures, the crafts and museums, galleries and libraries sectors’ digital services exports are zero – which we know is not the case.

Many UK YouTube channels, for example, are watched by millions of viewers across the world. It is through these types of platforms that the creative industries export audiovisual content, music, and tutorials. Such platforms and the content they offer, however, may not be registered as a service export. This is due to difficulties capturing data for business models such as those offering free content and based on advertising revenues.

There are also structural challenges with collecting data on such exports. Often, it is difficult for digital intermediaries to determine the point of sale and purchase. The borderless way in which many global firms operate presents additional complications and the origin of the creative content, and of those who consume it, is frequently hard to track.

This brings me to the vexed question of productivity growth in the new machine age. In the Deloitte – Monday Briefing – Thoughts on the global economy – from 30th April, the author reflects on the discussions which occurred at the annual global gathering of Deliotte’s economic experts. I’m cherry picking, of course, the whole article is well worth reading: –

Despite discussion of recession risks I was struck by a cautious optimism about the long-term outlook. There was a general view that the slowdown in productivity growth in the West has been overstated, partly because of problems in capturing gains from technological change and quality improvements. As a result most of us felt that Western economies should be able to improve upon the lacklustre growth rates seen in the last ten years.

We agreed too that apocalyptic media stories about new technologies destroying work were overcooked; technology would continue to create more jobs than it destroys. The challenge would be to provide people with the right skills to prosper. The question was, what skills? We had a show of hands on what we would recommend as the ideal degree subjects for an 18-year-old planning for a 40-year career. Two-thirds advocated STEM subjects, so science, technology, engineering and maths. A third, myself included, opted for humanities/liberal arts as a way of honing skills of expression, creativity and thinking.

Mr Stewart ends by referring to a letter to the FT from Dr Lawrence Haar, Associate Professor at the University of Lincoln, in which he argues that poor UK productivity is a function of the low levels of UK unemployment. In other words, when everyone, even unproductive workers, are employed, productivity inevitably declines:-

…it does not have to be this way. Some economies, including Singapore, Switzerland and Germany, combine low unemployment and decent productivity growth. The right training and education can raise productivity rates for lower skilled workers.

This theme of productivity growth supported by the right education and training is at the heart of a recent paper written by Professor Shackleton of the IEA – Current Controversies No. 62 – Robocalypse Now? IEA – May 2018 – the essay cautions against the imposition of robotaxes and makes the observation that technology has always created new jobs, despite the human tendency to fear the unknown: why should the adoption of a new swath of technologies be different this time? Here is his introduction: –

It is claimed that robots, algorithms and artificial intelligence are going to destroy jobs on an unprecedented scale.

These developments, unlike past bouts of technical change, threaten rapidly to affect even highly-skilled work and lead to mass unemployment and/or dramatic falls in wages and living standards, while accentuating inequality.

As a result, we are threatened with the ‘end of work’, and should introduce radical new policies such as a robot tax and a universal basic income.

However the claims being made of massive job loss are based on highly contentious technological assumptions and are contested by economists who point to flaws in the methodology.

In any case, ‘technological determinism’ ignores the engineering, economic, social and regulatory barriers to adoption of many theoretically possible innovations. And even successful innovations are likely to take longer to materialise than optimists hope and pessimists fear.

Moreover history strongly suggests that jobs destroyed by technical change will be replaced by new jobs complementary to these technologies – or else in unrelated areas as spending power is released by falling prices. Current evidence on new types of job opportunity supports this suggestion.

The UK labour market is currently in a healthy state and there is little evidence that technology is having a strongly negative effect on total employment. The problem at the moment may be a shortage of key types of labour rather than a shortage of work.

The proposal for a robot tax is ill-judged. Defining what is a robot is next to impossible, and concerns over slow productivity growth anyway suggest we should be investing more in automation rather than less. Even if a workable robot tax could be devised, it would essentially duplicate the effects, and problems, of corporation tax.

Universal basic income is a concept with a long history. Despite its appeal, it would be costly to introduce, could have negative effects on work incentives, and would give governments dangerous powers.

Politicians already seem tempted to move in the direction of these untested policies. They would be foolish to do so. If technological change were to create major problems in the future, there are less problematic policies available to mitigate its effects – such as reducing taxes on employment income, or substantially deregulating the labour market.

Professor Shackleton provides a brief history of technological paranoia. Riccardo added a chapter entitled ‘On Machinery’ to the third edition of his ‘Principles of Political Economy and Taxation,’ stating: –

‘I am convinced that the substitution of machinery for human labour is often very injurious to the interests of the class of labourers’.

While Marx, writing only a few decades later, envisaged a time when man would be enabled to: –

‘…to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner… without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.’

As for Keynes essay on the, ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren’, his optimism is laudable if laughable – 15 hour working week anyone?

The paranoia continues, nonetheless – The Economist – A study finds nearly half of jobs are vulnerable to automation – April 2018 – takes up the story:-

A wave of automation anxiety has hit the West. Just try typing “Will machines…” into Google. An algorithm offers to complete the sentence with differing degrees of disquiet: “…take my job?”; “…take all jobs?”; “…replace humans?”; “…take over the world?”

Job-grabbing robots are no longer science fiction. In 2013 Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University used—what else?—a machine-learning algorithm to assess how easily 702 different kinds of job in America could be automated. They concluded that fully 47% could be done by machines “over the next decade or two”.

A new working paper by the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries, employs a similar approach, looking at other developed economies. Its technique differs from Mr Frey and Mr Osborne’s study by assessing the automatability of each task within a given job, based on a survey of skills in 2015. Overall, the study finds that 14% of jobs across 32 countries are highly vulnerable, defined as having at least a 70% chance of automation. A further 32% were slightly less imperilled, with a probability between 50% and 70%. At current employment rates, that puts 210m jobs at risk across the 32 countries in the study.

For a robust analysis, if not refutation, of the findings of Frey and Osborne, I refer you back to Professor Shackleton’s IEA paper. He is more favourably disposed towards the OECD research, which is less apocalyptic in its conclusions. He goes on to find considered counsel in last year’s report from McKinsey Global Institute (2017) A Future that Works: Automation Employment and Productivity.

The IEA paper highlights another factor which makes it difficult to assess the net impact of technological progress, namely, the constantly changing nature of the labour market. As the table below reveals it has hardly been in stasis since the turn of the millennium: –

Percentage change in employment 2001-2017, selected occupations

Notes: April-June of years. Figures in brackets are April-June 2017 levels of employment.

Source: Author’s calculation from ONS

The job losses are broadly predictable; that technology has usurped the role of the travel agent is evident to anyone who booked a flight, hotel or hire-car online recently. For economists there are always challenges in capturing the gains; back in 1987 Robert Solow, a recipient of the Nobel prize from economics, famously observed, ‘You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics’ – perhaps the technology has been creating more jobs than thought. Does the 170% rise in Animal Care and Control owe a debt to technology? You might be inclined to doubt it but the 400,000 Uber drivers of London probably do. We are still seeking signs in the economic data for something we know instinctively should be evident.

Between the mis-measurement of economic activity (if technology is being under-estimated to the tune of 24% in the creative industries sector to what extent are productivity gains from technology being underestimated elsewhere?) and the ever changing employment landscape, I believe the human race will continue to be employed in a wide and varied range of increasingly diverse roles. If some of the more repetitive and less satisfying jobs are consigned to robots and machine learning computer code, so much the better for mankind. For more on, what is sometimes termed, the routinisation of work, this working paper from Bruegel – The impact of industrial robots on EU employment and wages: A local labour market approach – April 2018 is inciteful. They examine six EU countries and make comparisons, or highlighting contrasts, with the patterns observed in the US. Their conclusions are somewhat vague, however, which appears to be a function of the difficulty of measurement: –

We only find mixed results for the impact of industrial robots on wage growth, even after accounting for potential endogeneity and potential offsetting effects across different population or sectoral groups.

…We believe that future research on the topic should focus on exploiting more granular data, to explore whether insignificant aggregate effects (on wages) are to the result of counterbalancing developments happening at the firm level.

Bruegel refrain from proposing cuts to personal taxation as favoured by the IEA, suggesting that a more complex policy response may be required, however, their conclusions are only marginally negative. I am inclined to hope that market forces may be allowed to deal with the majority of the adjustment; they have worked well if history is any guide.

Conclusions and investment opportunities

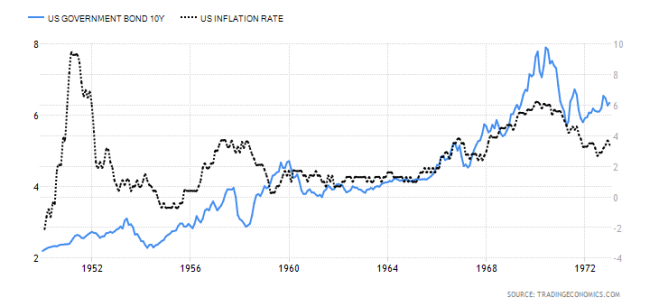

Ignoring the fact that we are nine years into an equity bull market and that interest rates are now rising from their lowest levels ever recorded, the long term potential for technology remains supportive for equity markets, for earnings growth and for productivity. If history repeats, or even if it simply rhymes, it should also be good for employment.

With interest rates looking more likely to rise than fall over the next few years, companies will remain reticent to invest in capital projects. Buying back stock and issuing the occasional special dividend will remain the policy du jour. Assuming we do not suffer a repeat of the great financial recession of 2008 – and that remains a distinct possibility – the boon of technology will create employment with one invisible hand as it creatively destroys it with the other (with apologies to Smith and Schumpeter). If governments can keep their budgets in check and resist the temptation to siphon off investment from the productive sectors of the economy (which, sadly, I doubt) then, in the long run, the capital investment required to create the employment opportunities of the future will materialise.