Macro Letter – No 73 – 24-03-2017

Can a multi-speed European Union evolve?

- An EC white paper on the future of Europe was released at the beginning of the month

- A multi-speed approach to EU integration is now considered realistic

- Will a “leaders and laggards” approach to further integration work?

- Will progress on integration enable the ECB to finally taper its QE?

At the Malta Summit last month German Chancellor Angela Merkel told reporters:-

We certainly learned from the history of the last years, that there will be as well a European Union with different speeds that not all will participate every time in all steps of integration.

On March 1st the European Commission released a white paper entitled the Future of Europe. This is a discussion document for debate next week, when members of the EU gather in Rome to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome.

The White Paper sets out five scenarios for the potential state of the Union by 2025:-

Scenario 1: Carrying On – The EU27 focuses on delivering its positive reform agenda in the spirit of the Commission’s New Start for Europe from 2014 and of the Bratislava Declaration agreed by all 27 Member States in 2016. By 2025 this could mean: Europeans can drive automated and connected cars but can encounter problems when crossing borders as some legal and technical obstacles persist. Europeans mostly travel across borders without having to stop for checks. Reinforced security controls mean having to arrive at airports and train stations well in advance of departure.

Scenario 2: Nothing but the Single Market – The EU27 is gradually re-centred on the single market as the 27 Member States are not able to find common ground on an increasing number of policy areas. By 2025 this could mean: Crossing borders for business or tourism becomes difficult due to regular checks. Finding a job abroad is harder and the transfer of pension rights to another country not guaranteed. Those falling ill abroad face expensive medical bills. Europeans are reluctant to use connected cars due to the absence of EU-wide rules and technical standards.

Scenario 3: Those Who Want More Do More – The EU27 proceeds as today but allows willing Member States to do more together in specific areas such as defence, internal security or social matters. One or several “coalitions of the willing” emerge. By 2025 this could mean that: 15 Member States set up a police and magistrates corps to tackle cross-border criminal activities. Security information is immediately exchanged as national databases are fully interconnected. Connected cars are used widely in 12 Member States which have agreed to harmonise their liability rules and technical standards.

Scenario 4: Doing Less More Efficiently – The EU27 focuses on delivering more and faster in selected policy areas, while doing less where it is perceived not to have an added value. Attention and limited resources are focused on selected policy areas. By 2025 this could mean A European Telecoms Authority will have the power to free up frequencies for cross-border communication services, such as the ones used by connected cars. It will also protect the rights of mobile and Internet users wherever they are in the EU.A new European Counter-terrorism Agency helps to deter and prevent serious attacks through a systematic tracking and flagging of suspects.

Scenario 5: Doing Much More Together – Member States decide to share more power, resources and decision-making across the board. Decisions are agreed faster at European level and rapidly enforced. By 2025 this could mean: Europeans who want to complain about a proposed EU funded wind turbine project in their local area cannot reach the responsible authority as they are told to contact the competent European authorities. Connected cars drive seamlessly across Europe as clear EU-wide rules exist. Drivers can rely on an EU agency to enforce the rules.

There is not much sign of a multi-speed approach in the above and yet, on 6th March the leaders of Germany, France, Italy and Spain convened in Versailles where they jointly expressed the opinion that allowing the EU to integrate at different speeds would re-establish confidence among citizens in the value of collective European action.

There are a couple of “general instruments”, contained in existing treaties, which give states some flexibility; ECFR – How The EU Can Bend Without Breaking suggests “Enhanced Cooperation” and “Permanent Structured Cooperation”(PESCO) as examples, emphasis mine:-

Enhanced cooperation was devised with the Amsterdam Treaty…in 1997, and revised in successive treaty reforms in Nice and Lisbon. Enhanced cooperation is stipulated as a procedure whereby a minimum of nine EU countries are allowed to establish advanced cooperation within the EU structures. The framework for the application of enhanced cooperation is rigid: It is only allowed as a means of last resort, not to be applied within exclusive competencies of the union. It needs to: respect the institutional framework of the EU (with a strong role for the European Commission in particular); support the aim of an ever-closer union; be open to all EU countries in principle; and not harm the single market. In this straitjacket, enhanced cooperation has so far been used in the fairly technical areas of divorce law and patents, and property regimes for international couples. Enhanced cooperation on a financial transaction tax has been in development since 2011, but the ten countries cooperating on this have struggled to come to a final agreement.

PESCO allows a core group of member states to make binding commitments to each other on security and defence, with a more resilient military and security architecture as its aim. It was originally initiated at the European Convention in 2003 to be part of the envisaged European Defence Union. At the time, this group would have consisted of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. After disagreements on defence spending in this group and the referendum defeat for the European Constitution which meant the end of the Defence Union, a revised version of PESCO was added into the Lisbon treaty. This revised version allows for more space for the member states to decide on the binding commitments, which of them form the group, and the level of investment. However, because of its history, some member states still regard it as a top-down process which lacks clarity about how the groups and criteria are established. So far, PESCO has not been used, but it has recently been put back on the agenda by a group of EU member states.

These do not get the EU very far, but the ECFR go on to mention an additional Schengen-style approach, where international treaties of EU members can be concluded outside of the EU framework. These treaties can later be adopted by other EU members.

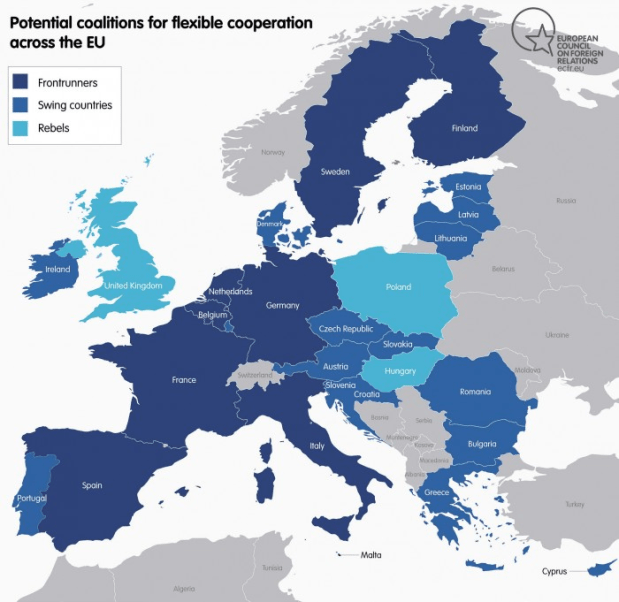

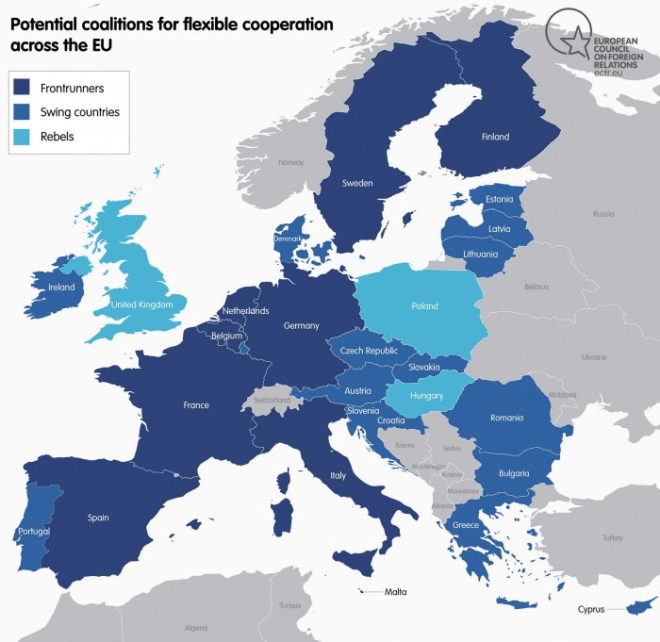

As part of their research the ECFR carried out more than 100 interviews with government officials and experts at universities and think-tanks across the 28 member states to discover their motivation for adopting a more flexible approach. The chart below shows the outcomes:-

Source: ECFR

Interestingly, in two countries, Denmark and Greece, officials and experts believe that more flexibility will result in greater fragmentation. Nonetheless, officials and experts in Croatia, Finland, Germany, Italy, Latvia, and Spain are in favour of embracing a more flexible approach. Benelux and France remain sceptical. Here is how the map of Europe looks to the ECFR:-

Source: ECFR

The timeline for action is likely to be gradual. President Juncker’s plans to develop the ideas contained in the white paper in his State of the Union speech in September. The first policy proposals may be drafted in time for the European Council meeting in December. It is envisaged that an agreed course of action will be rolled out in time for the European Parliament elections in June 2019.

Can Europe wait?

Two years is not that long a time in European politics but financial markets may lack such patience. Here is the Greek government debt repayment schedule prior to the European Parliament Elections:-

Source: Wall Street Journal

This five year chart shows the steady rise in total Greek government debt:-

Source: Tradingeconomics, Bank of Greece

Greek debt totalled Eur 326bln in Q4 2016, the debt to GDP ratio for 2015 was 177%. Italy’s debt to GDP was a mere 133% over the same period.

ECB dilemma

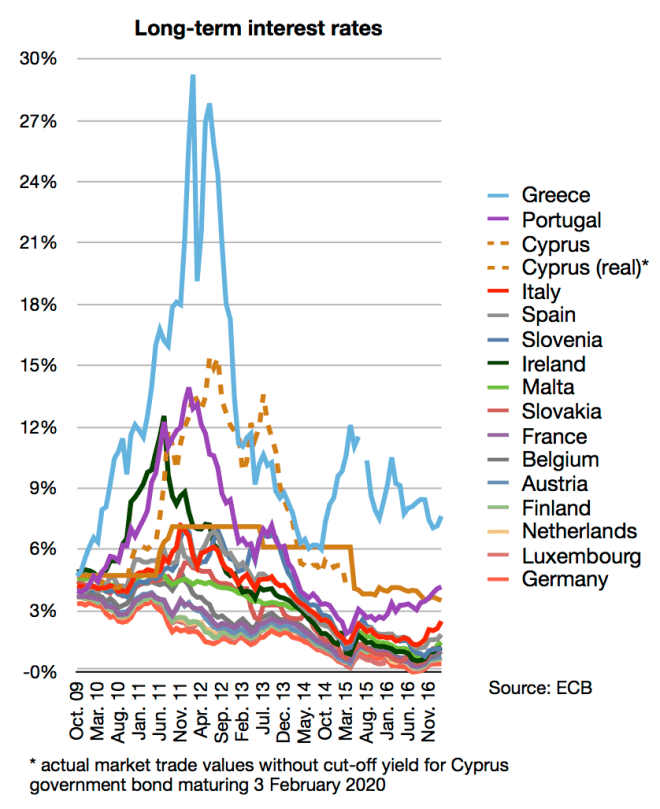

The ECB would almost certainly like to taper its quantitative easing, especially in light of the current tightening by the US. It reduced its monthly purchases from Eur 80bln per month to Eur 60bln in December but financial markets only permitted Mr Draghi to escape unscathed because he extended the duration of the programme from March to December 2017. Further reductions in purchases may cause European government bond spreads to diverge dramatically. Since the beginning of the year 10yr BTPs have moved from 166bp over 10yr German Bunds to 2.11% – this spread has more than doubled since January 2016. The chart below shows the evolution of Eurozone long-term interest rates between October 2009 and November 2016:-

Source: ECB

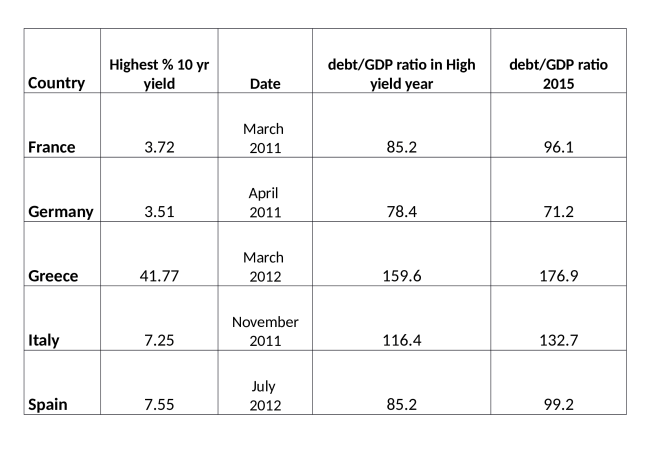

In 2011 the Euro Area debt to GDP ratio was 86%, by 2015 it had reached 91%. The table below shows the highest 10yr yield since the great financial crisis for a selection of Eurozone government bonds together with their ratios of debt to GDP. It goes on to show the same ratio at the end of 2015. Only Germany is in a stronger position today than it was during the Eurozone crisis in terms of its debt as a percentage of its GDP:-

Source: Trading Economics

Since these countries bond markets hit their yield highs during the Eurozone Crisis, Greece, Italy and Spain have seen an improvement in GDP growth, but only Spain is likely to achieve sufficient growth to reduce its debt burden. If the ECB is to cease killing the proverbial fatted calf, a less profligate fiscal approach is required.

Euro Area GDP averaged slightly less than 1.8% per annum over the last two years, yet the debt to GDP ratio only declined a little over 1% from its all-time high. Further European integration sounds excellent in theory but in practice any positive impact on economic growth is unlikely to be evident for several years.

EU integration has been moving at different speeds for years, if anything, the process has been held back by attempts to move in unison. There are risks of causing fragmentation with both approaches, either within countries or between them.

Conclusions and Investment Opportunities

Another Eurozone financial crisis cannot be ruled out this year. The political uncertainty of the Netherlands is past, but France may yet surprise. Once Germany has voted in September, it will be time to focus on the endeavours of the ECB. Their asset purchase programme is scheduled to end in December.

I would expect this programme to be extended once more, if not, the stresses which nearly tore the Eurozone asunder in 2011/2012 are likely to return. The fiscal position of the Euro Area is only slightly worse than it was five years ago, but, having flirted with the lowest yields ever recorded, bond markets have considerably further to fall in percentage terms than in during the previous crisis.

Spanish 10yr Bonos represents a better prospect than Italian 10yr BTPs, but one would have to endure negative carry to set up this spread trade: look for opportunities if the spread narrows towards zero. German Bunds are always likely to act as the safe haven in a crisis and their yields have risen substantially in the past year, yet at less than ½% they are 300bp below their “safe-haven” level of April 2011.

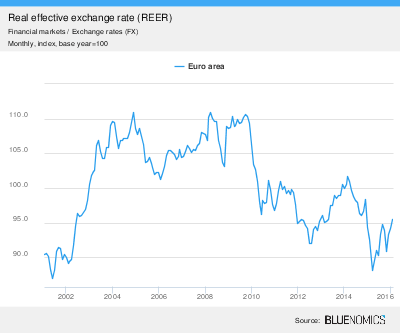

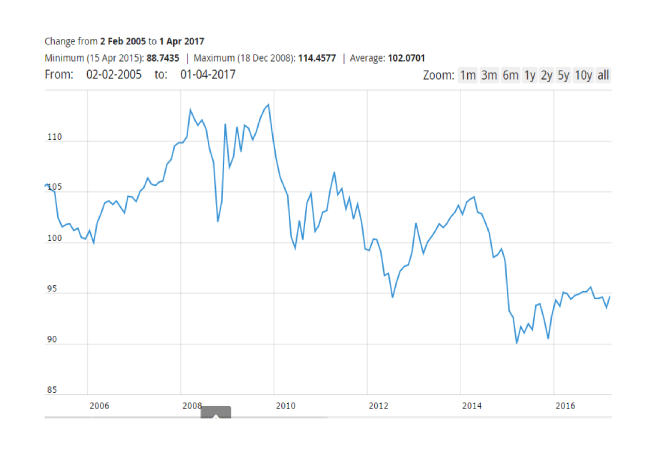

The Euro is unlikely to rally in this environment. The chart below shows the Euro Effective Exchange Rate since 2005:-

Source: ECB

The all-time low for the Euro is 82.34 which was the level is plumbed back in October 2000. This does sound an outlandish target during the next debacle.

Euro weakness would, however, be supportive for export oriented European stocks. The weakness that stocks would initially suffer, as a result of the return of the Euro crisis, would quickly be reversed, in much the same manner that UK stocks were pummelled on the initial Brexit result only to rebound.