Macro Letter – No 98 – 08-06-2018

Italy and the repricing of European government debt

- The yield spread between 10yr BTPs and Bunds widened 114bp in May

- Populist and anti-EU politics were the catalyst for this repricing of risk

- Spain, Portugal and Greece all saw yields increase as Bund yields declined

- The ECB policy of OMT should help to avoid a repeat of 2011/2012

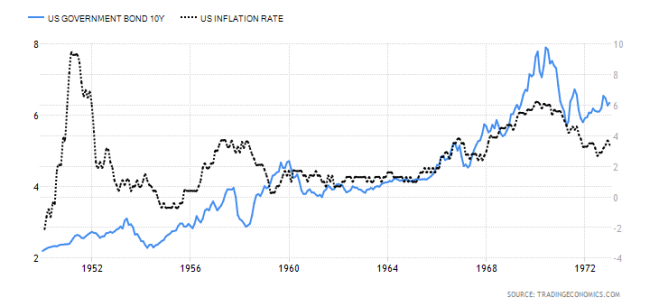

I have never been a great advocate of long-term investment in fixed income securities, not in a world of artificially low official inflation indices and fiat currencies. Given the de minimis real rate of return I regard them as trading assets. I will freely admit that this has led me to make a number of investment mistakes, although these have generally been sins of omission rather than actual investment losses. The Italian political situation and the sharp rise in Italian bond yields it precipitated, last week, is, therefore, some justification for an investor like myself, one who has not held any fixed income securities since 2010.

An excellent overview of the Italian political situation is contained in the latest essay from John Mauldin of Mauldin Economics – From the Front Line – The Italian Trigger:-

Italy had been without a government since its March 4 election, which yielded a hung parliament with no party or coalition holding a majority. The Five Star Movement and Lega Nord finally reached a deal, to most everyone’s surprise since those two parties, while both broadly populist, have some big differences. Nonetheless, they found enough common ground to propose a cabinet to President Sergio Mattarella.

Italian presidents are generally seen as rubberstamp figureheads. They really aren’t supposed to insert themselves into the process. Yet Mattarella unexpectedly rejected the coalition’s proposed finance minister, 81-year-old economist Paolo Savona, on the grounds Savona had previously opposed Italy’s eurozone membership. This enraged Five Star and Lega Nord, who then ended their plans to form a government and threatened to impeach Mattarella.

The whole article is well worth reading and goes on to look at debt from a global perspective. John anticipates what he calls, ‘The Great Reset,’ when the reckoning for the excessive levels of debt arrives.

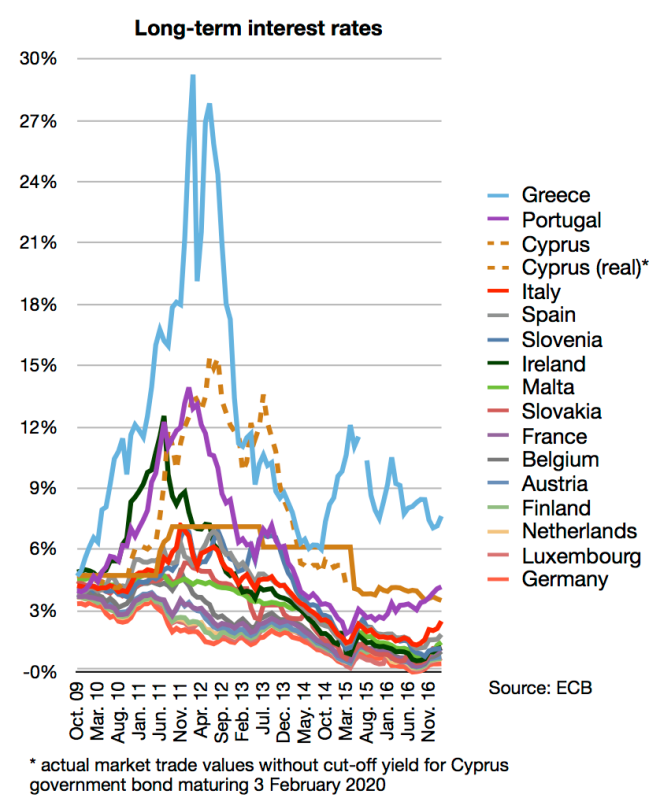

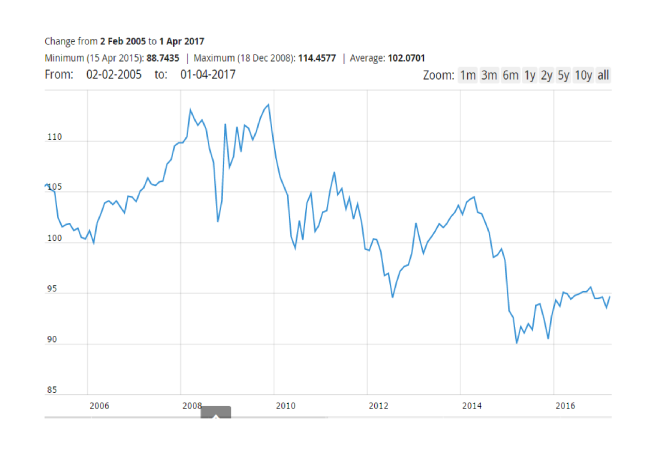

Returning to the repricing of Eurozone (EZ) debt last month, those readers who have followed my market commentaries since the 1990’s, might recall an article I penned about the convergence of European government bond yields in the period preceding the introduction of the Euro. At that juncture (1998) excepting Greece, every bond market, whose government was about to adopt the Euro, was trading at a narrower credit spread to 10yr German bunds than the yield differential between the highest and lowest credit in the US municipal bond market. The widest differential in the muni-market at that time was 110bp. It was between Alabama and California – remember this was prior to the bursting of the Tech bubble.

In my article I warned about the risk of a significant repricing of European credit spreads once the honeymoon period of the single currency had ended. I had to wait more than a decade, but in 2010/2011 it looked as if I might be vindicated – this column is not entitled In the Long Run without just cause – then what one might dub the Madness of Crowds of Central Bankers intervened, saved the EZ and consigned my cautionary oracles, on the perils of the quest for yield, to the dustbin of history.

In the intervening period, since 2011, I have watched European yields inexorably converge and absolute yields turn negative, in several EZ countries, with a temerity which smacks of permanence. I have also arrived at a new conclusion about the limits of credit risk within a currency union: that they are governed by fiat in much the same manner as currencies. As long as the market believes that Mr Draghi will do, ‘…whatever it takes,’ investors will be enticed by relatively small yield enhancements.

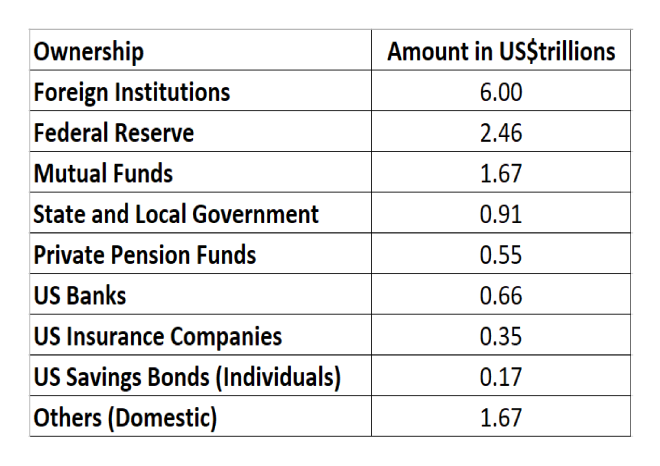

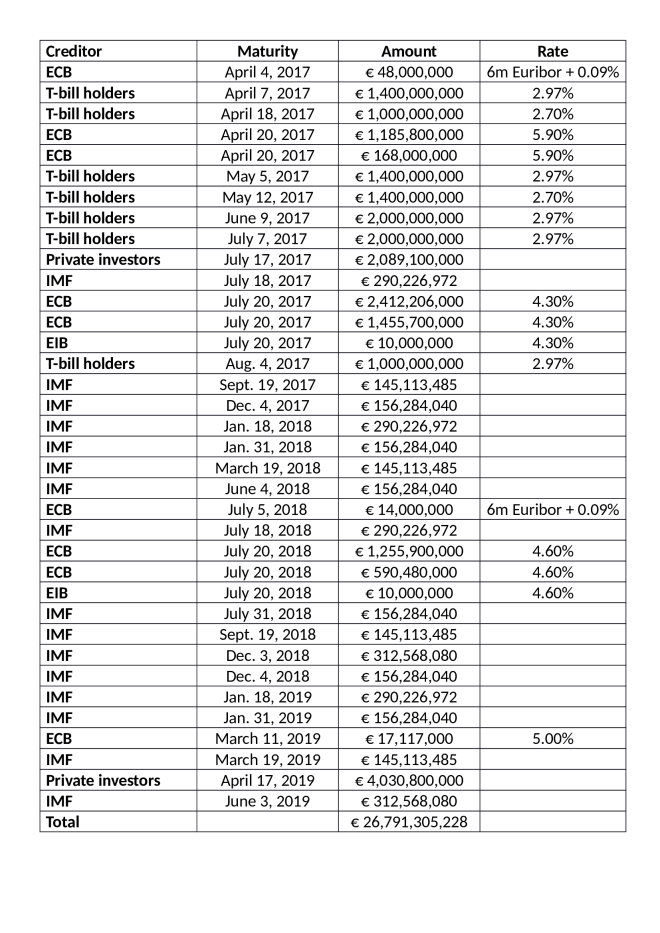

Let me elaborate on this newly-minted theory by way of an example. Back in March 2012, Greek 10yr yields reached 41.77% at that moment German 10yr yields were a mere 2.08%. The risk of contagion was steadily growing, as other peripheral EZ bond markets declined. Greece, in and of itself, was and remains, a small percentage of EZ GDP, but, as Portuguese and Spanish bonds began to follow the lead of Greece, the fear at the ECB – and even at the Bundesbank – was that Italy might succumb to contagion. Due to its size, the Italian bond market, was then, and remains today, the elephant in the room.

During the course of last month, European bond markets diverged. The table below shows the change in 10yr yields between 1st and 31st May:-

Source: Investing.com

A certain degree of contagion is evident, although the PIGS have lost an ‘I’ as Irish Gilts have escaped the pejorative acronym.

At the peaks of the previous crisis, Irish 10yr Gilts made a yield high of 14.61% in July 2011, at which point their spread versus 10yr Bunds was 11.34%. When Italy entered her own period of distress, in November of that year, the highest 10yr BTP yield recorded was 7.51% and the spread over Germany reached 5.13%. By the time Greek 10yr yields reached their zenith, in March 2012, German yields were already lower and Irish and Italian spreads had begun to narrow.

During the course of last month the interest rate differential between 10yr Bunds and their Irish, Greek and Italian counterparts widened by 41, 100 and 114bp respectively. Italian 10yr yields closed at 4.25% over Bunds, less than 100bp from their 2011 crisis highs. With absolute yields significantly lower today (German 10yr yields were 2.38% in November 2011 they ended May 2018 at 36bp) the absolute percentage return differential is even higher than during the 2011 period. At 2.72% BTPs offer a return which is 7.5 times greater than 10yr Bunds. Back in 2011 the 7.51% yield was a little over three times the return available from 10yr Bunds.

I am forced to believe the reaction of the BTP market has been excessive and that spreads will narrow during the next few months. If I am incorrect in my expectation, it will fall to Mr Draghi to intervene. The Outright Monetary Transactions – OMT – policy of the ECB allows it to purchase a basket of European government bonds on a GDP weighted basis. If another crisis appears immanent they could adjust this policy to duration weight their purchases. It would then permit them to buy a larger proportion of the higher yielding, higher coupon bonds of the southern periphery. There would, no doubt, be complaints from those countries that practice greater fiscal rectitude, but the policy shift could be justified on investment grounds. If the default risk of all members of the EZ is equal due to the political will of the European Commission, then it makes sense from an investment perspective for the ECB to purchase higher yielding bonds if they have the same credit risk. A new incarnation of the Draghi Put could be implemented without too many objections from Frankfurt.

Conclusions and investment opportunities

I doubt we will see a repeat of the 2011/2012 period. Lightening seldom strikes twice in the same way. The ECB will continue with its QE programme and this will ensure that EZ government bond yields remain at artificially low levels for the foreseeable future.

Unusually, I have an actionable trade idea: caveat emptor! I believe the recent widening of the 10yr Italian BTP/Spanish Bonos spread has been excessive. If there is bond market contagion, as a result of the political situation in Italy, Bonos yields may have difficulty defying gravity. If the Italian political environment should improve, the over-sold BTP market should rebound. If the ECB are forced to act to avert a new EZ crisis by increasing OMT or implementing a duration weighted approach to QE, Italy should benefit more than Spain until the yield differential narrows.