Macro Letter – No 59 – 15-07-2016

Uncharted British waters – the risk to growth, the opportunity to reform

- Uncertainty will delay investment and damage growth near term

- A swift resolution of Britain’s trade relations with the EU is needed

- Without an aggressive liberal reform agenda growth will be structurally lower

- Sterling will remain subdued, Gilts, trade higher and large cap stocks well supported

Look, stranger, on this island now

The leaping light for your delight discovers,

Stand stable here

And silent be,

That through the channels of the ear

May wander like a river

The swaying sound of the sea.

W.H. Auden

Source: Captain Greenvile Collins – Great Britain’s Coasting Pilot – 1693

Captain Greenvile Collins was the Hydrographer in Ordinary – to William and Mary. His coastal pilot was the first, more or less, accurate guide to the coastline of England, Scotland and Wales, prior to this period mariners had relied mainly on Dutch charts. Collins’s charts do not comply with the convention of north being at the top and south at the bottom – the print above, of the Thames estuary, has north to the right. This, and the extract from W. H. Auden with which I began this letter, seem appropriate metaphors for the new way we need to navigate the financial markets of the UK post referendum.

Sterling has borne the brunt of the financial maelstrom, weakening against the currencies of all our major trading partners. Gilts have rallied on expectations of further largesse from the Bank of England (BoE) and a more generalised international flight to quality in “risk-free” government bonds. This saw Swiss Confederation bonds trade at negative yields to maturity out to 48 years.

With interest rates now at historic lows around the developed world and investors desperate for yield, almost regardless of risk, equity markets have remained well supported. Many individual UK companies with international earnings have made new all-time highs. Banks and construction companies have not fared so well.

Now the dust begins to settle, we have the more challenging task of anticipating the longer term implications of the British schism, both for the UK and its European neighbours. In this letter I will focus principally on the UK.

A Return to the Astrolabe?

Source: University of Cambridge

The Greeks invented the astrolabe sometime around 200BCE. The one above of Islamic origin and dates from 1309. Before the invention of the sextant this was the only reliable means of navigation.

Our aids to navigation have been compromised by the maelstrom of Brexit – it’s not quite a return to the Astrolabe but we may have lost the use of GPS and AIS.

This week the OECD was forced to suspend the publication of its monthly Composite Leading Indicators (CLI). Commenting on the decision they said:-

The CLIs cannot…account for significant unforeseen or unexpected events, for example natural disasters, such as the earthquake, and subsequent events that affected Japan in March 2011, and that resulted in a suspension of CLI estimates for Japan in April and May 2011. The outcome of the recent Referendum in the United Kingdom is another such significant unexpected event, which is affecting the underlying expectation and outturn indicators used to construct the CLIs regularly published by the OECD, both for the UK and other OECD countries and emerging economies.

It will be difficult to draw any clear conclusions from the economic data produced by the OECD or other national and international agencies for some while.

Speaking to the BBC prior to the referendum, OECD Secretary General, Angel Gurria had already suggested that UK growth would be damaged:-

It is the equivalent to roughly missing out on about one month’s income within four years but then it carries on to 2030. That tax is going to be continued to be paid by Britons over time.

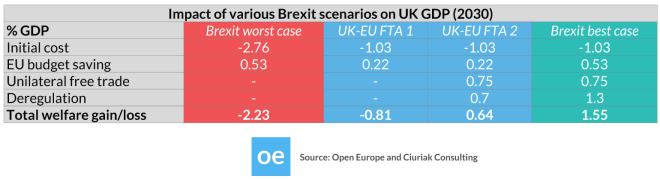

Back in March Open Europe – What if…? The consequences, challenges and opportunities facing Britain outside the EU put it thus:-

UK GDP could be 2.2% lower in 2030 if Britain leaves the EU and fails to strike a deal with the EU or reverts into protectionism. In a best case scenario, under which the UK manages to enter into liberal trade arrangements with the EU and the rest of the world, whilst pursuing large-scale deregulation at home, Britain could be better off by 1.6% of GDP in 2030. However, a far more realistic range is between a 0.8% permanent loss to GDP in 2030 and a 0.6% permanent gain in GDP in 2030, in scenarios where Britain mixes policy approaches.

…Based on economic modelling of the trade impacts of Brexit and analysis of the most significant pieces of EU regulation, if Britain left the EU on 1 January 2018, we estimate that in 2030:

In a worst case scenario, where the UK fails to strike a trade deal with the rest of the EU and does not pursue a free trade agenda, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) would be 2.2% lower than if the UK had remained inside the EU.

In a best case scenario, where the UK strikes a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU, pursues very ambitious deregulation of its economy and opens up almost fully to trade with the rest of the world, UK GDP would be 1.6% higher than if it had stayed within the EU.

Source: Open Europe, Ciuriak Consulting

Given that UK annual GDP growth averaged 2.46% between 1956 and 2016, the range of outcomes is profoundly important. GDP forecasts are always prone to error but the range of outcomes indicated above is exceedingly broad – divination might prove as useful.

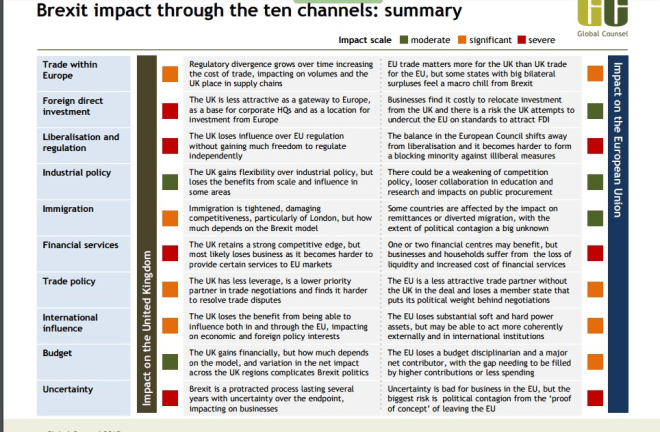

Also published prior to the referendum Global Counsel – BREXIT: the impact on the UK and the EU assessed the prospects both for the UK and EU in the event of a UK exit. The table below is an excellent summary, although I don’t entirely agree with all the points nor their impact assessment:-

Source: Global Counsel

Another factor to consider, since the June vote, is whether the weakness of Sterling will have a positive impact on the UK’s chronic balance of payments deficit. This post from John Ashcroft – The Saturday Economist – The great devaluation myth suggests that, if history even so much as rhymes, it will not:-

If devaluation solved the problems of the British Economy, the UK would have one of the strongest trade balances in the global economy…. the depreciation of sterling in 2008 did not lead to a significant improvement in the balance of payments. There was no “re balancing effect”. We always argued this would be the case. History and empirical observation provides the evidence.

There was no improvement in trade as a result of the exit from the ERM and the subsequent devaluation of 1992, despite allusions of policy makers to the contrary. Check out our chart of the day and the more extensive slide deck below.

Seven reasons why devaluation doesn’t improve the UK balance of payments …

1 Exporters Price to Market…and price in Currency…there is limited pass through effect for major exporters

2 Exporters and importers adopt a balanced portfolio approach via synthetic or natural hedging to offset the currency risks over the long term

3 Traders adopt a medium term view on currency trends better to take the margin boost or hit in the short term….rather than price out the currency move

4 Price Elasticities for imports are lower than for exports…The Marshall Lerner conditions are not satisfied…The price elasticities are too limited to offset the “lost revenue” effect

5 Imports of food, beverages, commodities, energy, oil and semi manufactures are relatively inelastic with regard to price. The price co-efficients are much weaker and almost inelastic with regard to imports

6 Imports form a significant part of exports, either as raw materials, components or semi manufactures. Devaluation increases the costs of exports as a result of devaluation

7 There is limited substitution effect or potential domestic supply side boost

8 Demand co-efficients are dominant

Curiouser and Curiouser – the myth of devaluation continues. The 1992 experience….

“The UK’s trade performance since the onset of the economic downturn in 2008 has been one of the more curious developments in the UK economy” according to a recent report from the Office for National Statistics. “Explanation beyond exchange rates: trends in UK trade since 2007.

We would argue, it is only curious for those who choose to ignore history.

Much reference is made to the period 1990 – 1995 when the last “great depreciation led to an improvement in the balance of payments” – allegedly. Analysing the trade in goods data [BOKI] from the ONS own report demonstrates the failure of depreciation to improve the net trade in goods performance in the period 1990 – 1995.

Despite the fall in sterling, the inexorable structural decline in net trade in goods continued throughout. As we have long argued would be the case, in the most recent episode. Demand co-efficients are powerful, the price co-efficients much weaker and almost inelastic with regard to imports. Check out the slide show below for more information.

The conclusions from the ONS report do not add up. Curiouser and Curiouser, policy makers just like Alice, sometimes choose to believe in as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

A brief history of devaluation from 1925 onwards….

The great devaluation of 1931 – 24%

In 1925, the dollar sterling exchange rate was $4.87. Britain had readopted the gold standard. Unfortunately, the relative high value of the pound placed considerable pressure on the trade and capital account, the balance of payments problem developed into a “run on the pound”. The UK left the gold standard in 1931, the floating pound quickly dropped to $3.69, providing an effective devaluation of 24%. The gain, if such it was, could not be sustained. Over the next two years, confidence in the currency returned, the dollar weakened, sterling rallied in value to a level of $5.00 but…Fears of conflict in Europe placed pressure on the sterling. In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II the rate dropped to $3.99 from $4.61. In March, 1940, the British government pegged the value of the pound to the dollar, at $4.03.

The great devaluation of 1949 – 30%

Post war, Britain was heavily indebted to the USA. Despite a soft loan agreement with repayments over fifty years, the pound remained once again under intense pressure In 1949 Stafford Cripps devalued the pound by over 30%, giving a rate of $2.80.

The great devaluation of 1967 – 14%

In 1967 another “balance of payments” crisis developed in the British economy with a subsequent “run on the pound. Harold Wilson announced, in November 1967, the pound had been devalued by just over 14%, the dollar sterling exchange rate fell to $2.40. This the famous “pound in your pocket” devaluation. Wilson tried to reassure the country by pointing out that the devaluation would not affect the value of money within Britain.

In 1971, currencies began to float, depreciation not devaluation became the guideline

In 1977, sterling fell against the dollar with pound plummeting to a low of $1.63 in the autumn 1976. Another sterling crisis and a run on the pound. The British government was forced to borrow from the IMF to bridge the capital gap. The princely sum of £2.3 billion was required to restore confidence in the pound.

By 1981, the pound was trading back at the $2.40 level but not for long. Parity was the pursuit by 1985 as the pound fell in value to a month low of $1.09 in February 1985.

In the late 1980s, Chancellor Lawson was pegging the pound to the Deutsche Mark to establish some form of stability for the currency. In October of 1990, Chancellor Major persuaded Cabinet to enter the ERM, the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. The DM rate was 2.95 to the pound and $1.9454 against the dollar.

Less than two years later, Britain left the European experiment.

The strains of holding the currency within the trading band had pushed interest rates to 12% in September, with some suggestions that rates would have to rise to 20% to maintain the peg.

In September 1992, Chancellor Lamont announced the withdrawal from the ERM. The Pound fell in value against the dollar from $1.94 to $1.43, an effective depreciation of 26%. According to the wider Bank of England Exchange rate the weighted depreciation was 15%.

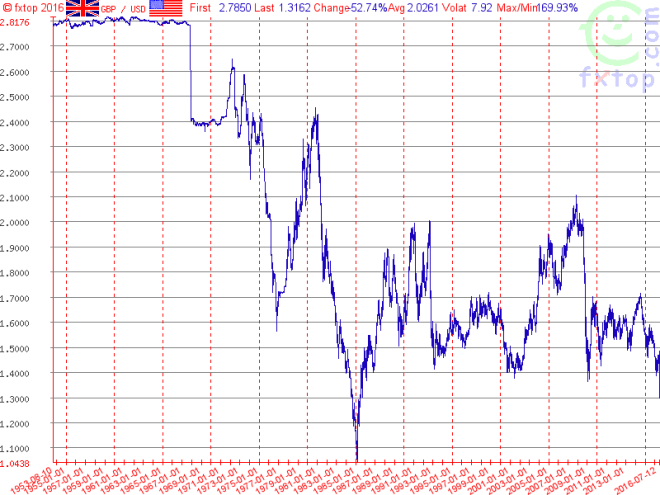

The chart below shows GBPUSD since 1953, it doesn’t capture everything mentioned above but it highlights the volatility and terminal decline of the world’s ex-reserve currency:-

Source: FX Top

Reform, reform, reform

The UK needs to renegotiate terms with the EU as quickly as possible in order to minimise the damage to UK and global economic growth. I believe there are four options: –

EEA – the Norwegian Option

Pros

- Maintain access to the Single Market in goods and services and movement of capital.

- Ability to negotiate own trade deals.

- Least disruptive alternative to EU membership.

Cons

- Commitment to free movement of people and the provision of welfare benefits to EU citizens.

- Accept EU regulation but have no influence over them.

- Must comply with “rules of origin” – which impose controls on the use of products from outside the EU in goods which are subsequently exported within the EU. The cost of determining the origin of products is estimated to be at least 3.0% – the average tariff on goods from the US and Australia is 2.3% under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

- Comply with EU rules on employment, consumer protection, environmental protection and competition policy.

- Pay an annual fee to access the Single Market, although less than for full EU membership.

EFTA – the Swiss Option

Pros

- Maintain access to the Single Market in goods.

- Ability to negotiate own trade deals.

- Greater independence over the direction of social and employment law.

Cons

- Commitment to free movement of people.

- Must comply with “rules of origin”.

- Restricted access to the EU market in services – particularly financial services.

WTO – the Default Option

Pros

- Subject to Most Favoured Nation tariffs under WTO guidelines. In 2013, the EU’s trade-weighted average MFN tariff was 2.3% for non-agricultural products.

- Ability to negotiate own trade deals.

- Independence over legislation.

Cons

- Tariffs on agricultural products range from 20% to 30%.

- Tariffs for automobiles are 10%.

- Services sector would face higher levels of non-tariff barriers such as domestic laws, regulations and supervision. Services made up 37% of total UK exports to the EU in 2014 – the WTO option will be costly.

Bilateral Free-Trade Agreement – the Canadian Option

Pros

- Negotiate a bilateral trade agreement with the EU – sometimes called the Canada option after the, still unratified, Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

Cons

- Must comply with “rules of origin” – if it mirrors the CETA deal.

- Services are only partially covered.

- Negotiations may take years.

The quickest solution would be the WTO default option, the least cathartic would be to join the EEA. I suspect we will end up somewhere between these two extremes; The Peterson Institute – Theresa May—More Merkel than Thatcher? Is of a different opinion:-

To survive politically at home, May must deliver Brexit at almost any cost, suggesting that she might well in the end be compelled to accept a “hard Brexit” that puts the UK entirely outside the internal market. Lacking a public mandate in a fractious party that retains only a slim parliamentary majority, May not surprisingly opposes new general elections, which would focus on Brexit and thus easily cost the Conservatives their majority, along with their new prime minister’s job. Unless the UK suffers substantially additional economic hardship in the coming years, the next UK elections may well occur as late as 2020.

For the financial markets there is a certain elegance in the “hard Brexit” WTO option. Uncertainty is removed, unilateral trade negotiations can be undertaken immediately and the other options remain available in the longer term.

Beyond renegotiation with the EU there is a broader reform agenda. Dust off your copy of Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, this could see a return to the liberal policies, of smaller government and freer trade, which we last witnessed in the 1980’s. The IEA’s Ryan Bourne wrote an article this week for City AM – Forget populist executive pay curbs: Prime Minister May should embrace these six policies to revitalise growth in which he advocated:-

1) Overhaul property taxation: the government should abolish both council tax and stamp duty entirely and replace them with a single tax on the “consumption” of property – i.e. a tax on imputed rent. It is well known among economists that taxes on transactions like stamp duty are highly damaging, and we have already seen the high top rates significantly slow transactions since April.

2) Abolish corporation tax entirely: profit taxes discourage capital investment by lowering returns, which makes workers less productive and results in lower wage growth. In a globalised world, profits taxation also encourages capital to move elsewhere, both because it makes the UK less attractive as a location for “real” economic activity and because it creates incentives for avoidance through complex business structures. Rather than continuing this goose chase, let’s abolish it entirely and tax dividends at an individual level, as Estonia does.

Read more: Ignore Google’s corporation tax bill and scrap the tax altogether

3) Planning liberalisation: if you ask anyone to name the UK’s main economic problems, you’ll probably hear “poor productivity performance”, “a high cost of living” and “entrenched economic difficulties in some areas”. Constraining development through artificial boundaries and regulations is acknowledged to be a key driver of high house price inflation. Less acknowledged is that, for sectors like childcare, social care, restaurants and even many office-based industries, high rents and property prices raise other prices for consumers, with a dynamic strain on our growth prospects brought about by a reduction in competition and innovation. That’s not to mention the impact on labour mobility. Liberalisation of planning, including greenbelt reform – which May has sadly already seemingly ruled out – is probably the closest thing to a silver bullet as far as productivity improvements are concerned.

4) Sensible energy policy: the UK government has gone further than many EU countries on the “green agenda”. But the EU’s framework, with binding targets for renewables, has certainly helped shape policy in the direction of subsidies and subsidy-like obligations and interventions. Even if one accepts the need to reduce carbon emissions, an economist would suggest the implementation of either a straight carbon tax or, less optimally, a cap-and-trade scheme, rather than the current raft of interventions which make energy more expensive than it need be.

5) Agricultural liberalisation: exiting the EU Common Agricultural Policy gives us the opportunity to reassess agricultural policy. The UK should gradually phase out all subsidies, as New Zealand did, opening up the sector to global competition. This improved agricultural productivity in that country significantly. Combined with a policy of unilateral free trade, it would deliver substantially lower food prices for consumers too.

6) Deregulation: in the long term, Britain should extricate itself from the Single Market and May should set up a new Office for Deregulation, tasked with examining all existing EU laws and directives, with the clear aim of removing unnecessary burdens and lowering costs. In particular, this should focus on labour market regulation, financial services, banking and transport

In a departure from my normal focus on the nexus of macroeconomics and financial markets I wrote a reformist article last week for the Cobden Centre – A Plan to Engender Prosperity in Perfidious Albion – from Pariah to Paragon; in it, I made some additional reform proposals:-

Banking Reform: The financialisation of the UK economy has reached a point where productive, long term capital investment is in structural decline. Increasing bank capital requirements by 1% per annum and abolishing a zero weighting for government securities would go a long way to reversing this pernicious trend.

Monetary Reform: The key to long term prosperity is productivity growth. The key to productivity growth is investment in the processes of production. Interest rates (the price of money) in a free market, act as the investment signal. Free banking (a banking system without a lender of last resort) is a concept which all developed countries have rejected. Whilst the adoptions of Free banking is, perhaps, too extreme for credible consideration in the aftermath of Brexit, a move towards the free-market setting of interest rates is desirable to attempt to avert any further malinvestment of capital.

Labour Market Reform: A repeal of the Working Time Directive and the Agency Workers Directive would be a good start but we must resist the temptation to close our borders to immigration. Immigrants, both regional and international, have been essential to the economic prosperity of Britain for centuries. There will always be individual winners and losers from this process, therefore, the strain on public services should be addressed by introducing a contribution-based welfare system that ensures welfare for all – migrants and non-migrants – contingent upon a record of work.

Educational Reform: investment in technology to deliver education more efficiently would yield the greatest productivity gains but a reform of the incentives based on individual choice would also help to improve the quality of provision.

Free Trade Reform: David Ricardo defined the economic law of comparative advantage. In the aftermath of the UK exit from the EU it would be easy for the UK to slide towards introspection, especially if our European trading partners close ranks. We should resist this temptation if at all possible; it will undermine the long term productivity of the economy. We should promote global free trade, unilaterally, through our membership of the World Trade Organisation. In the last 43 years we have lost the art of negotiating trade deals for ourselves. It will take time to reacquire these skills but gradual withdrawal from the EU by way of the EEA/EFTA option would give the UK time to adjust. The EEA might even prove an acceptable longer term solution. I suspect the countries of EFTA will be keen to collaborate with us.

We should apply to rejoin the International Organization for Standardization , the International Electrotechnical Commission , and the International Telecommunication Union (all of which are based in Geneva) and, under the auspices of EFTA, we can rejoin the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC), the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), and the Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM).

Conclusion

Financial markets will remain unsettled for an extended period; domestic capital investment will be delayed, whilst international investment may be cancelled altogether. If growth slows, and I believe it will, further easing of official interest rates and renewed quantitative easing are likely from the BoE. Gilts will trade higher, pension funds and insurance companies will continue to purchase these fixed income assets but the BoE will acquire an ever larger percentage of outstanding issuance. In 2007 Pensions and Insurers held nearly 50%, with Banks and Building Societies accounting for 17% of issuance. By Q3 2014 Pensions and Insurers share had fallen to 29%, Banks and Building Societies to 9%. Over seven years, the BoE had acquired 25% of the entire Gilt issuance.

Companies with foreign earnings will be broadly immune to the vicissitudes of the UK economy, but domestic firms will underperform until there is more clarity about the future of our relationship with Europe and the rest of the world. The UK began trade talks with India last week and South Korea has expressed interest in similar discussions. Many other nations will follow, hoping, no doubt, that a deal with the UK can be agreed swiftly – unlike those with the EU or, indeed, the US. The future could be bright but markets will wait to see the light.

Pingback: Hard Brexit maths – walking away – In the Long Run