.

.

Macro Letter – No 4 – 31-01-2014

Whither the UK – From Tantalus to Sisyphus?

It has been a long time since I have reviewed the UK economy and the prospects for our financial markets but the recent spate of positive economic news deserves investigation.

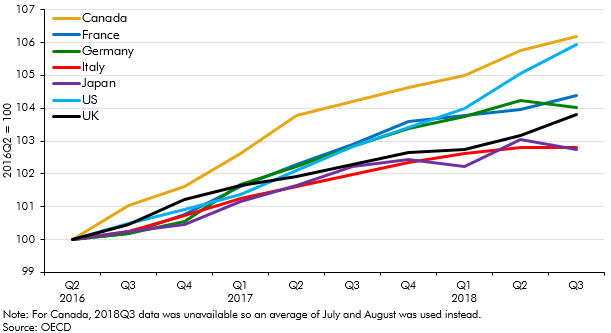

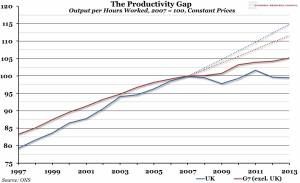

Sterling

To begin I have enclosed a chart of GBP/USD. You will notice that despite a significant strengthening of GBP, in line with the improving economic data, we still have a distance to travel before returning to the pre-Northern Rock range. The near-term trend looks clear but a comprehensive break above 1.70 is required for confirmation.

GBP/USD FX 10yr – source fxtop.com

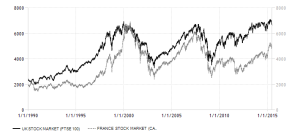

To understand why GP/USD may return to its pre-crisis range one needs to consider why it has been languishing in purgatory since 2008/2009. Partly this is due to the size of the UK financial services sector, where regulatory headwinds remain fierce, and partly the direction of long-term interest rates globally. Here is a chart of 10 year Gilt yields:-

10yr Gilt yield – 10yr Monthly – source investorsintelligence.com Stockcube Research Ltd

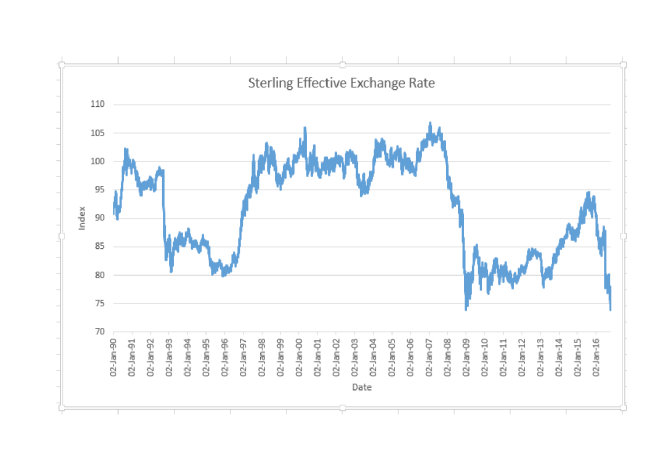

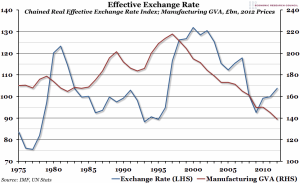

Of course short and long term interest rates have declined in most countries since the Great Recession but traditionally GBP was a “carry-currency” due to our structurally higher inflation rates. The “sea-change” in interest rate differentials has seen the “carry-trader” depart this sceptre isle. There are a number of other factors including the arrival of a coalition government in 2010, a significant decline in the UK housing market and a collapse in the UK export sector, despite the precipitous decline of sterling against its trading partners. Financial services went out of fashion and North Sea oil and gas production took an unfortunate nose-dived simultaneously.

The chart below showing the GBP Trade-Weighted Index is from Ashraf Laidi . It is a couple of years old but it’s still valid, the annotation is his:-

Source – AshrafLaidi.com

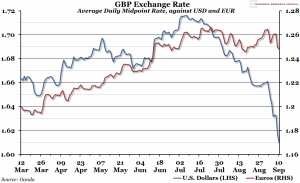

Gilts

Looking at the chart of 10 year Gilt yields above, you will notice that yields bottomed in mid-2012 whilst GBP/USD took until 2013 to begin its recovery. The external factor driving Gilt yields to their nadir was the Eurozone crisis, however, since Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech (July 26th 2012) Gilt yields have begun to normalise in a similar manner to the US. Meanwhile Eurozone rates have converged lower and German 10 year Bund rates have remained relatively low.

Looking ahead it is not unreasonable to expect Gilt yields to go higher, but, with GBP rising and inflation falling this is likely to be a gradual process; added to which the Bank of England (BoE) have been softening their tone on prospective interest rate increases.

Here’s a quote from MPC member Ben Broadbent speaking at the LSE on 17th January: –

The final and more general point is to caution against inferring too much about future growth from its current composition. Of course there’s a risk the recovery could falter. But, if it does, it will probably be because of more fundamental problems – a failure of productivity to respond to stronger demand, for example, or continuing stagnation in the euro area – not any imbalance in expenditure or income per se. These are outcomes, not determinants, of the economic cycle. As we shall see, they are poor predictors of future growth.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2014/024.aspx

On 23rd January Ian McCafferty reiterated the MPC’s position on rates: –

…the MPC sees no immediate need to increase interest rates, even if unemployment reaches 7% in the near future.

McCafferty goes on to discuss capital expenditure which, along with productivity growth, has been weak during the early stages of the recovery.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2014/027.aspx

Also on 23rd January MPC memberPaul Fisher, after explaining why the BoE allowed inflation to remain above target for so long, went on to opine: –

We are very conscious that the headwinds have not gone away: much of Europe and some other parts of the world continue to struggle for sustained growth; fiscal consolidation in the UK (and elsewhere) is likely to continue for a while to come; and the financial sector still needs some rebuilding. Indeed, the official production and construction data released earlier this month were rather disappointing, reminding us that strong growth from here on is by no means guaranteed.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2014/028.aspx

Fisher goes on to explain that unemployment, and the composition of employment, are key metrics in their thought process. The whole speech is also a fascinating insight into the MPCs approach and their ideas on forward guidance.

BoE Governor – Mark Carney addressed the CBI at Davos on 24th January: he discussed the UK economy and the need to reach “escape velocity”: –

After the Great Moderation and the Great Recession, there are several reasons why it will be years before any superlatives are attached to this recovery.

First, for all the talk of austerity and deleveraging, the aggregate debt burdens of advanced economies have actually increased; with their total non-financial sector debt rising by 25% relative to GDP since 2007. Balance sheet repair in the public and private sectors will exert a persistent drag on major economies for some time.

Second, the need to rebalance demand from deficit to surplus countries endures. Given the adjustment pressures on the former, without progress on rebalancing, robust and sustainable global growth will remain an aspiration.

Third, confidence, while improved, remains subdued. Recognising that the end isn’t nigh is far from marking the normalisation of business and consumer sentiment. Given past shocks and modest prospects, business investment in particular remains hesitant across the advanced world. On balance, corporations remain more focused on reducing operating expenditures than increasing capital expenditures.

… Nevertheless, it appears that the recovery will need to be sustained for a period before productivity gains can resume in earnest. The latest data show that more than a quarter of a million jobs were created in a three-month period – the biggest increase since records began in 1971. As a result, unemployment seems to be falling at a pace that will reach our 7% threshold materially earlier than we had expected.

Crucially, unemployment remains above the level that is likely to be consistent with maintaining inflation at the target in the medium term. It is not just that nearly three quarters of a million more people are out of work than before the crisis; another three quarters of a million more people are involuntarily working part time.

The effect of this slack in the labour market is evident in wage inflation, which is at around 1% so that, even with weak productivity, unit labour cost growth remains below 2%.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2014/705.aspx

All of these comments concerning lack of productivity growth, elevated levels of unemployment, growth of part-time employment, lack of capital expenditure and international headwinds from the Eurozone, suggest that interest rates will stay low and the BoE will risk above target inflation to insure the economic recovery broadens and deepens. In this environment I see Gilts remaining in a relatively narrow range, even if inflation ticks higher once more.

Politics

On 29th January, Mark Carney spoke in Edinburgh on The economics of currency unions. The full speech is here: –

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2014/speech706.pdf

He attempted to be deliberately non-political – to judge by the press comment afterwards he failed – but it is a timely reminder that Scotland will vote on whether they remain in the Union on 18th September. The uncertainty surrounding the possible break-up of the Union and one what economic terms is another factor which will temper a broader based recovery.

Other political clouds on the horizon include the European Parliament elections (22nd to 25th May) where nationalist parties are expected to gain significant ground.

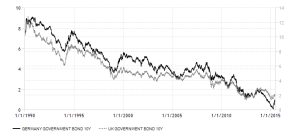

Equities

The FTSE100 has performed strongly since the beginning of 2013, in line with other developed country stock markets. The large dose of QE delivered by the BoE has underpinned this trend, but, now that the economy has regained some upward momentum, many commentators are becoming doubtful about the prospects for UK stocks – after all, lower interest rates are one of the most powerful drivers of equity market performance.

Firstly, I believe UK-centric stock momentum is increasing, but a number of external factors will be supportive of the UK equity market: –

- China has announced a rebalancing of their economy towards domestic consumption, even if this is at the expense of headline GDP growth. This makes inward foreign investment into China less attractive – I expect capital to flow back to UK and USA.

- Japan is attempting to deliver economic growth through what PM Abe has dubbed the “Three Arrows” policy, this has already seen a significant decline in the JPY and a new “quasi-carry trade” is being driven but expectation of relative government spending. The US has begun to taper (another $10bln just this week) and the UK might follow suit at some point this year, but Japan will continue with QE.

- Emerging markets have already started to react to the changed policy of the Federal Reserve: India, beginning last year, Argentina, South Africa and Turkey, have seen their currencies depreciate and respond with higher interest rates since the start of the year. Emerging market bonds have, needless the say, fallen sharply, prompting international investors to liquidate some of their investments. The reversal of more than a decade of Capital flows to emerging markets will support developed country currencies, especially those, like the UK, with Capital account surpluses.

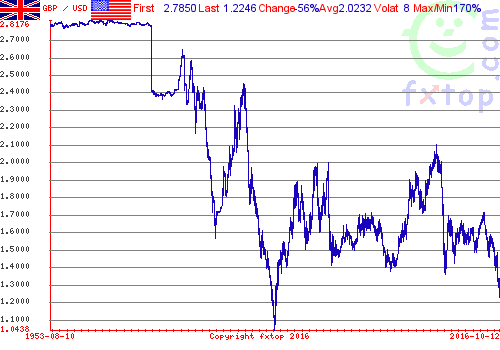

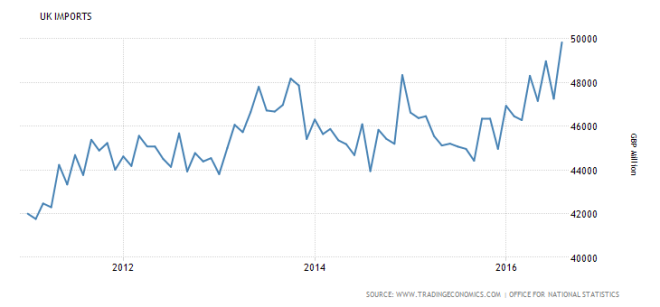

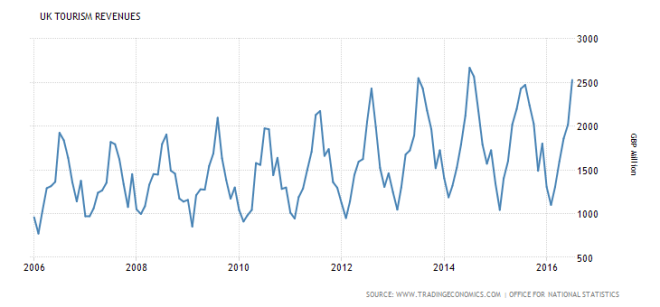

Secondly, UK Exports have remained resilient despite the strengthening of sterling.

Source – tradingeconomics.com

I have some caveats concerning UK equities however; banking and financial services firms are still under pressure due to regulatory change – a new report from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCAD) shows the UK falling to second place behind the USA; down more than 20% from its peak only seven years ago. The European Commission has just announced plans to stop all proprietary trading by Banks by 2017 – whilst this is likely to be challenged by UK, France and Germany it will lead to the postponement of any expansion plans in this area. Another sector which is under pressure is mining or commodity firms which are still suffering from the downturn in prices in 2013 – this tallies with my short-term concerns about emerging markets.

UK House Prices

A number of commentators have suggested that the recent strength of the UK economy has been largely driven by increased debt, especially mortgages. Government schemes such as “funding for lending” actively encouraged UK banks to lend more aggressively despite their balance sheet constraints.

MPC member David Mills, in a speech to the Dallas Federal Reserve, discussed housing last November:-

That problem with using monetary policy to stabilise the housing market would be acute if housing markets were overheating when the wider economy was not and consumer price inflation was low even though house price inflation was high.

…High leverage is at the heart of problems in housing market. Monetary policy and macro prudential policy can influence leverage. But more fundamentally, use of outside equity might be a way of permanently bringing down reliance upon debt financing.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2013/132.aspx

In other words the BoE is unlikely to be concerned about house price inflation and will use macroprudential measures rather than interest rates to stem its rise should it occur in isolation. This is clearly good for property but, in anticipation of the “Macroprudential Stick” other asset classes, such as equities, may benefit by association.

The housing market is finally recovering from the bottom up as the following chart makes clear: –

Source – Council for Mortgage Lenders

First time buyers have returned, perhaps because banks are more amenable about loan to value ratios but also because real house prices are well off their highs: –

Real House Prices since 1975 – source Nationwide Building Society

House price momentum appears to have turned higher once more – this chart, from MarketOracle.co.uk, uses data to November 2013:-

Source – MarketOracle.co.uk and Halifax

The December 2013 report from the Land Registry, published on 29th January, shows continued improvement: –

http://www.landregistry.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/71192/HPIReport20140122.pdf

Independent forecasts for UK property are strongly positive, here is a recent sampling:-

CBRE – 17% Rise by 2018 – Commercial property consultants

OBR – 20% Rise by end of 2018

Knight Frank – 24% rise by end of 2018 – Retail property specialists

Savills – 25% rise by end of 2018 – Retail property specialists

Why so strong? Because interest rates are low and therefore housing is relatively affordable. Here is one of my favourite measures of housing affordability from Moneystepper.com:-

UK Mortgage payment to income ratio – source Moneystepper.com

The author uses the Nationwide House Price Index, the BoE base rate plus 2% and the ONS after-tax income data.

For a more detailed investigation of the UK property market here is their post from November 2013, it’s the second of three articles:-

http://moneystepper.com/financial-planning/housing-bubble-uk-2/

Why Tantalus to Sisyphus?

Almost everything I’ve written so far has been positive for the UK economy and neutral or positive for UK markets. After unprecedented actions by the BoE, the “Tantalus Phase” appears to be over; growth that was just out of reach is now within our grasp, however, ahead of us lies the “Sisyphus Phase” where we have to pay the piper.

To begin with I want to look at money supply growth. Here is the Ratio of M4 to M0 from BoE data: –

Ratio of M4 to M0 – source Bank of England – John Phelan

An excellent article by John Phelan written for the Cobden Centre analyses this development in more detail: –

http://www.cobdencentre.org/2014/01/britains-inflationary-outlook

Since March 2009 Britain’s monetary base, also known as narrow money or M0, has increased by 321%. We can see that the majority of this is in the form of increased bank reserves, up 642% since March 2009.

This is just what we’d expect to see following the Bank of England’s Quantitative Easing, where the Bank creates new money and uses it to purchase bonds from banks – that new money becomes bank reserves. Those banks have sat on that money (not using it as a basis for new credit creation and feeding into M4) which is why, while narrow (M0) money has exploded, broad (M4) money has barely budged, increasing by just 7.4% since March 2009.

This relative restraint in M4 growth explains the relative restraint in inflation. There is no great mystery as to why banks which have just seen their assets tank and ravage their balance sheets should want to hold more reserves. The key question is what happens next.

A paper published in December 2013 by European Commission – The flow of credit in the UK economy and the availability of financing to the corporate sector – looks in more detail at the problem of the transmission of credit:-

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_paper/2013/pdf/ecp509_en.pdf

They conclude on an optimistic note: –

The flow of credit in the UK economy may be close to turning a corner in connection with recent improvements in the macroeconomic outturns and outlook, and as banks finish adapting to a new regulatory environment. Improving access to finance for firms and SMEs is set to remain a crucial element for driving the desirable rebalancing of the UK economy, fomenting investment and fostering the reallocation of resources to the most productive sectors of the economy throughout the on-going recovery.

The BoE – Corporate Credit Conditions Survey – Q4 2013 – released earlier this month, also suggests this process is starting to happen:-

Overall credit availability to the corporate sector was reported to have increased significantly in 2013 Q4; lenders have now reported an increase in availability for five consecutive quarters. Lenders cited market share objectives, competition from capital markets and an improvement in the economic outlook as factors that had contributed significantly to the increase in availability. All these factors were expected to contribute significantly to availability in 2014 Q1.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/other/monetary/ccs/creditconditionssurvey140108.pdf

Against this back-drop of improving conditions, however, it is important to realise that the combination of UK public and private sector debt is the second largest of any developed country on the planet relative to GDP – only Japan carries a greater burden. Academic research has shown that when the ratio of debt to GDP exceeds 260% to 275% this tends to act as a drag on economic growth.

The chart below is from 2012 but the situation has not improved.

Total Debt to GDP – source DailyMail – January 2012

UK Household debt is now at a record £1.43trln, although, it has fallen from 167% of income to 140% since 2008.

At some point in the future we will have a “reckoning” – probably when broad-based inflation begins to rise once more. Interest rates will rise dramatically to control credit growth. What the catalyst will be is difficult to say – a breakup of the Eurozone could lead to a collapse of GBP, the next major leg of a commodity super-cycle turbo-charged by the collapse of the Saudi regime – it’s best not to speculate, but, perhaps the longer term factor most likely to re-ignite the inflationary potential of the “great debasement” is demographic.

As the “Baby-boomers” finish retiring and downsizing the next leg of the demographic cycle will begin, with increased spending and consumption. When these “new-boomers” eclipse the “old-boomers” inflation will regain its power to decimate the value of money whilst at the same time asset prices will collapse under a deluge of foreclosures and debt default. The Sisyphian task will be to reduce the debt against the rising tide of servicing costs. But when will the next “Baby Boom” arrive?

Here is a fascinating chart from the ONS:-

UK Baby boom – source Office of National Statistics

According to ONS data, UK population growth to mid-2011 was the highest in 40 years. They predict that, should this trend continue, the UK will have the largest population of any country in Europe by 2050. Recent CML data shows the average age of first time house buyers to be 29/30 years. I therefore anticipate a “mini-baby boom” effect kicking in between 2015 and 2020, followed by a 10 year decline. From 2030 this pattern will reverse; by 2040 the next significant inflation wave will be in full swing.

This weekCharles Goodhart, speaking at the LSE predicted that “The Next Crisis” – which was the title of his speech – will occur around 2025/2026. Here’s the podcast, he starts his argument around 10 minutes in and make the case for 17 year cycles. Hence 2025/26 will see the next UK crisis which, he believes, will be more severe than the recent downturn due to a greater concentration on lending to the property sector, exacerbated by the regulatory curtailment of investment banking activity in favour of more traditional bank lending: –

http://www.lse.ac.uk/newsAndMedia/videoAndAudio/channels/publicLecturesAndEvents/player.aspx?id=2219

My expectation is that during the remainder of this decade demographic forces will be somewhat supportive of inflation but attempts to deleverage UK debt after 2020 will have more deflationary consequences.

Conclusion

Sterling looks well placed to move back into its pre-crisis range. Gilts are caught between inflationary and deflationary forces and should remain range-bound. UK Equities are likely to benefit from inward capital flows and UK property looks better than ever – barring a significant change in UK planning laws, this is my preferred UK asset class for 2014, and probably beyond.