Macro Letter – No 102 – 28-09-2018

UK Financial Services – Opportunities and Threats Post-Brexit – Short-term Pain, Long-term Gain?

- A Brexit deal is still no closer, but trade will not cease even if the March deadline passes

- In the short-term UK and EU economic growth will suffer

- Medium-term new arrangements will hold back capital investment

- Long-term, there are a host of opportunities, in time they will eclipse the threats

In a departure from the my usual format this Macro Letter is the transcript of a speech I gave earlier this week at the UK law firm, Collyer Bristow; Thomas Carlisle may have dubbed Economics ‘the dismal science,’ but I remain an optimist.

Setting aside the vexed question of whether Brexit will be hard, soft or stalled, the impact on financial services (and, indeed, the majority of UK trade in goods and services) will be dramatic.

Financial markets (and businesses in general) loathe uncertainty. Ever since the referendum result, investment decisions have been postponed or cancelled. When investment is being made it is generally tentative and defensive. Exporters and importers alike are striving to develop alternative strategies to maintain and protect their franchises.

As a long-term economic commentator, I try to look beyond the immediate impact of events, since near-term expectations are usually reflected in the valuation of an asset or currency. Brexit, however, is a particular challenge, not only due to near-term uncertainty but because policy decisions taken now and in the wake of the March 2019 deadline could set the UK economy on an unusually wide array of possible trajectories.

Near-term

To begin an analysis of the impact post-Brexit on financial services, there are several near-term threats; here are a selection: –

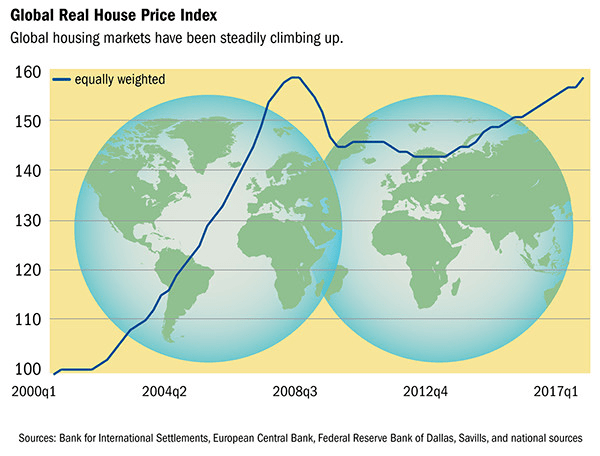

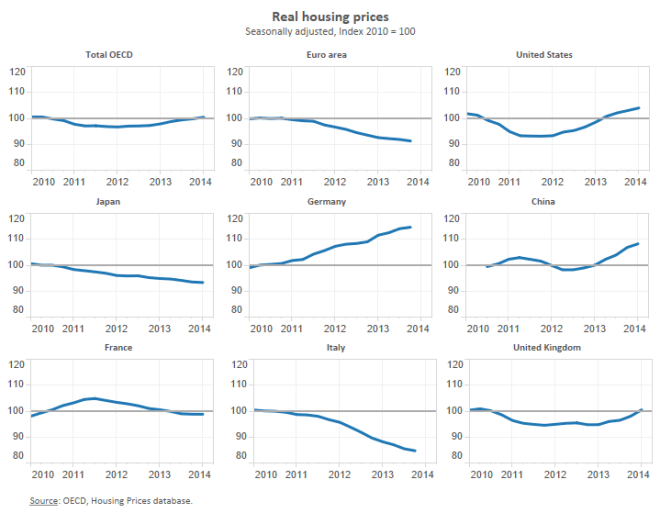

- House Prices

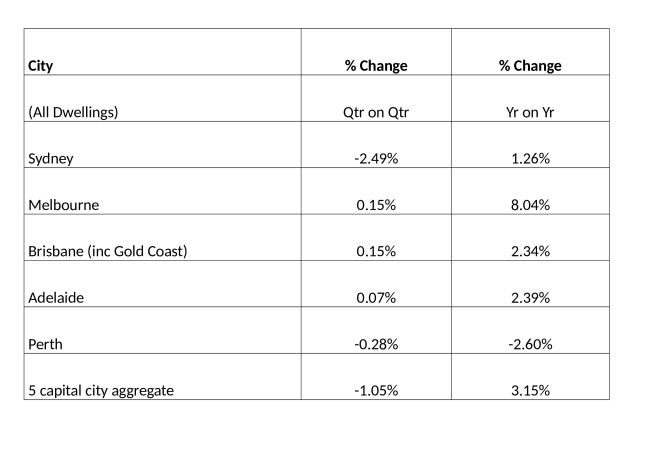

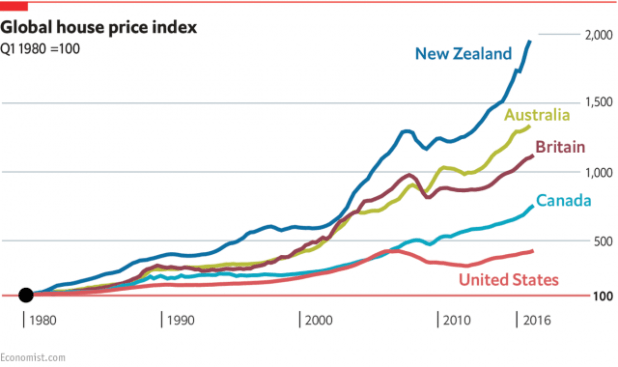

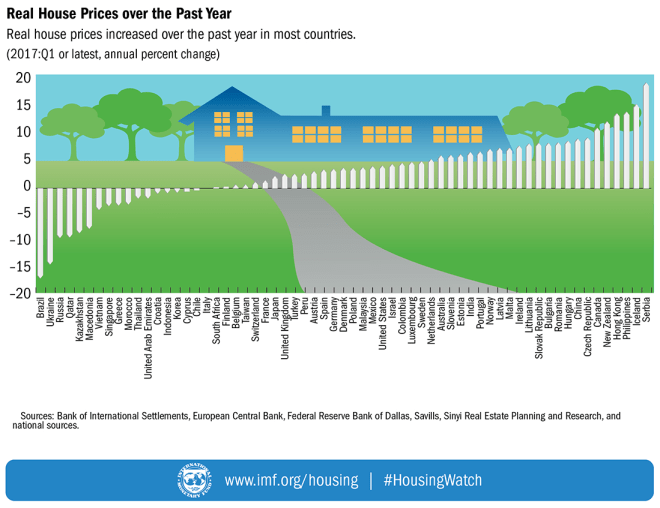

Earlier this month Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, warned cabinet ministers that a ‘no-deal’ on Brexit could see house prices decline by as much as one third and a rapid rise in defaults. The subsequent impact on financial institutions balance sheets and the inevitable curtailment of bank lending could be severe. Jacob Rees-Mogg even dubbed him, ‘The High Priest of Project Fear.’

- Passporting

Assuming no deal is agreed, the access which financial services providers in the UK have had to the EU27 will not be available after March 2019. Many existing contracts and licensing agreements will need to be rewritten.

- Regulatory equivalence

Divergence between the regulatory regime in the UK and Europe remains a distinct risk. The types of legal issues surrounding, for example, ISDA Master agreements (Deutsche Bank AG v Comune di Savona) will inevitably become more widespread.

- Systemic Risks to the Euro

The ECB is vocal in its mission to maintain control over the clearing and settlement of Euro denominated transactions. Many financial services activities which currently take place in the UK may need to be transferred to another EU country.

In the near-term, these types of factors will reduce trade and economic growth, both in the UK and, to a lesser degree, in Europe. In May 2017 I wrote an essay entitled ‘Hard Brexit Maths – Walking Away’ in which I estimated the negative impact a no-deal Brexit would have on the EU. The UK’s NIESR estimated the bill for a Hard Brexit to the UK at EUR66bln/annum. I guesstimated the cost of Hard Brexit to the EU at EUR 62bln/annum. Both forecasts will probably prove inaccurate.

The reduced free movement of workers from the EU is another significant factor. It will lead to a rise in a toxic combination of skill shortages (due to new immigration controls) and unemployment, as companies are forced to conserve capital to weather the inevitable economic slowdown.

There are, however, several near-term opportunities, here are a small selection: –

- Sterling weakness

The currency has already weakened. Whilst this may be inflationary it makes UK exports more competitive. Whether the UK can take advantage of currency weakness remains to be seen, history is not on our side in this respect.

- A US boom

Aided by a lavish tax cut, the US economy is growing faster than at any-time since the financial crisis, underpinning its currency. Its trade deficit is growing despite tariff barriers.

- US Trade policy

The Trump administration appears to have focused its ire on trade surplus countries, of which Germany is the largest European example. The UK is not under the White House microscope to the same degree.

Seizing the opportunity presented by these financial and geopolitical shifts is easier to speak of than to grasp. Nonetheless, just this month Absa Bank of South Africa (recently spun-off from Barclays) announced plans to open a London office to capitalise on post-Brexit opportunities connected with the fast-growing economies of Africa.

Medium-term

The medium-term risks will mostly be borne out of inertia. Until the shape of Brexit is clear, decisions will continue to be postponed. Once Brexit occurs there will be inevitable technical problems, stemming from systems issues and new procedures. Growth will slow further, business operating costs will need to be cut, employment in financial services (and elsewhere) will decline at exactly the moment when greater investment should be undertaken.

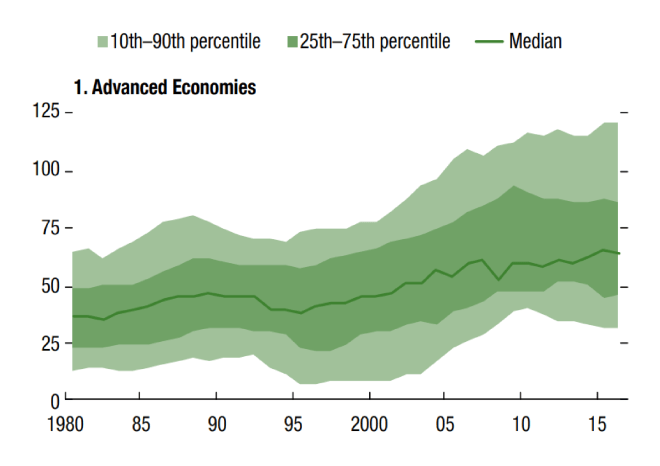

But, new trade deals will be negotiated, not just with Europe and the US, but also with the countries of the British Commonwealth, notably (but not just) India. Many of these countries are among the fastest growing economies in the world, often imbued with benign demographics. Here is a rapidly expanding working age population in need of capital investment and financial services. Ruth Lea, Chief Economist at Arbuthnot Latham has commentated on this subject at length during the last two years. In April she wrote: –

Commonwealth countries, taken together, have buoyant economic prospects and their share of global output continues to increase (especially in PPP terms). The EU28 share, in contrast continues to decline.

UK exports to the top eight Commonwealth countries rose by over 31% between 2006 and 2016, but total exports rose by 40%. And the share of UK exports going to the top eight Commonwealth countries fell from 7.5% in 2006 to 7.0% in 2016…

There is little doubt that Commonwealth countries have the potential to be significant growth markets for the UK’s exports, given their favourable growth prospects and demographics. This is all the more likely given the probability of trade deals with individual Commonwealth countries after Brexit.

Long-term

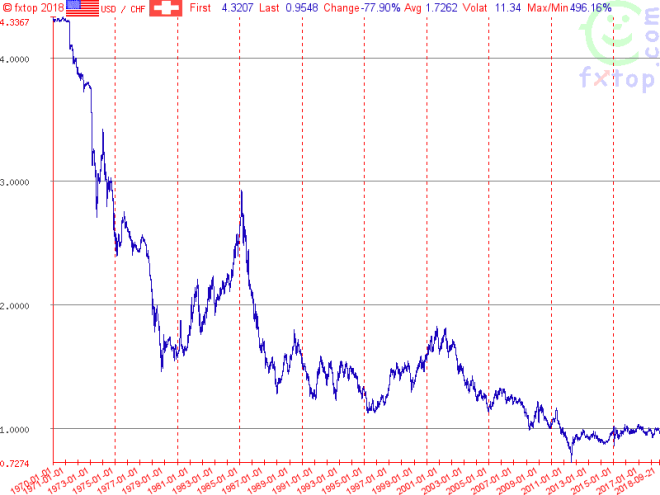

David Riccardo defined the law of comparative advantage just over two hundred years ago. Perhaps one of the best examples of the continuance of the phenomenon is Switzerland, which has seen its currency appreciate against the US$ by approximately 3% per year, every year since fiat currencies were freed from their shackles after the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971. Here is a chart of the US$/CHF exchange rate over the period: –

Source: fxtop.com

The Swiss turned to pharmaceuticals and other value-added businesses. The success of this strategy, despite a constantly appreciating currency, has spawned an entire industrial region – the Rhone-Alp economic area, which incorporates German, French, Italian and Austrian companies bordering Switzerland. This region is among the most economically productive in the EU.

The UK has an opportunity, post-Brexit, to focus on economic growth. As a trading nation, we should concentrate our efforts on re-forging links with the fast-growing countries of the Commonwealth, where the advantages of a common language and legal system favour the UK over other developed nations.

An example of this opportunity is in education. We have a world class reputation for education and training. Combine this redoubtable capability with the abundance of new technologies, which permit the delivery of content globally via the internet, and we can provide the full gamut of instruction, ranging from primary to tertiary and professional via a combination of video content, on-line examination and tailored digital collateral.

A recent MOOC (Mass Open On-line Course) In which I enrolled, attracted students from across the world. The course was dedicated to finance and among the students with whom I interacted was a Masi tribesman from Kenya who hoped to develop micro-finance solutions for the local farming community. The world is our veritable oyster.

Conclusion – The Bigger Picture

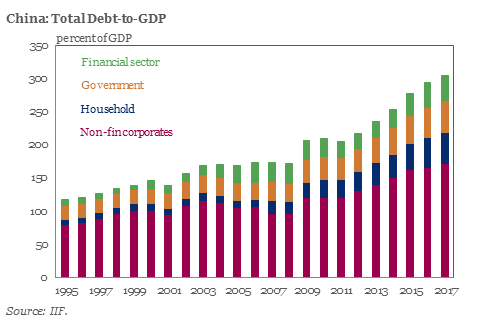

The economies of the developed world are growing more slowly than those of developing nations. Providing goods and services to the fastest growing economies makes economic sense. Many of the largest companies listed on the UK stock market have been oriented to take advantage of this dynamic for decades. Brexit is proving to be cathartic, we should embrace change: the sooner the better.

The Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpter, described the cycle of economic development as including a period of ‘creative destruction’. Brexit could be an extreme version of this process. The patterns of trade which have developed since the end of WW2 have been concerned with promoting cohesion between European nations, but, as Hyman Minsky famously noted, ‘stability creates the seeds of instability.’ I believe the political polarisation seen in Europe and elsewhere is a reaction against the success of the global financial and economic system and the institutions and alliances created to insure its success. We are entering an era of change and Brexit is but one personification of a growing trend. Technology has shrunk the world, empowered the individual and (in the process) undermined the influence of nation states and international institutions. Individual freedom is ascendant but with freedom comes responsibility.

One of the greatest challenges facing the UK and other developed nations, in the long run, is the provision of pensions and health insurance to an increasingly ageing population. Many of the financial products required by these ageing consumers are ones in which the UK is a world leader. The developing world is rapidly growing richer too. Their citizens will require these self-same products and services. Brexit is an opportunity to look forward rather than back. If we embrace change we will thrive, if not change will occur regardless. Post-Brexit there will be considerably pain but, if we manage to learn from history, there can also be long-term gain.