.

.

.

.

Macro Letter – No 3 – 17 -01-2014

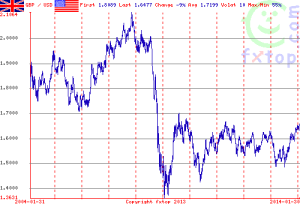

European Markets and Unification

During 2013 developed market equities were the top performing major asset class. The US and UK had justification for rising since the effects of quantitative easing appear to have stimulated some economic activity. Europe, however, has less reason for strength since ECB policies have been less accommodative. The performance of the German mid-cap index aside, European equity market performance in 2013 was largely due to receding fears of the break-up of European currency union. This has been a major contributor to the decline in peripheral bond yields as the chart below shows.

.

.

.

.

Source: Bloomberg

Banking Union and the ECB

In 2014 the focus will be on deepening unification, commencing with a European Banking Union. Der Spiegel reports: –

Not Fit for the Next Crisis: Europe’s Brittle Banking Union – 19th December 2013

http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/weak-eu-banking-union-could-have-dangerous-side-effects-a-940065.html

When German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, a trained lawyer, announced an agreement on Wednesday night in Brussels on the long negotiated EU banking union, observers might have been left thinking that he is precisely this type of lawyer.

On paper, Schäuble and his negotiators are right about very many points. They succeeded in ensuring that in 2016, the Single Resolution Mechanism will go into effect alongside the European Union banking supervisory authority. The provision will mean that failing banks inside the euro zone can be liquidated in the future without requiring German taxpayers to cover the costs of mountains of debt built up by Italian or Spanish institutes.

They also backed the European Commission, which wanted to become the top decision-maker when it comes to liquidating banks. The Commission will now be allowed to make formal decisions, but only in close coordination with national ministers from the member states.

But it goes even farther. Negotiators from Berlin have also created an intergovernmental treaty, to be negotiated by the start of 2014, that they believe will protect Germany from any challenges at its Constitutional Court that might arise out of the banking union.

They also established a very strict “liability cascade” that will require bank shareholders, bond holders and depositors with assets of over €100,000 ($137,000) to cover the costs of a bank’s liquidation before any other aid kicks in. The banks are also required to pay around €55 billion into an emergency fund over the next 10 years. Until that fund has been filled, in addition to national safeguards, the permanent euro bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism, will also be available for aid. However, any funds would have to be borrowed by a national government on behalf of banks, and that country would also be liable for the loan. This provision is expected to be in place at least until 2026.

The government in Berlin put a strong emphasis on preventing the ESM, with its billions in funding, from being used to recapitalize debt-ridden European banks. Schäuble was alone with this position during negotiations, completely isolating himself from the other 16 finance ministers from euro-zone countries. Brussels insiders report that it was “extremely unusual because normally at least a few countries share Germany’s position.”

The article goes on to highlight some of the weaknesses with this agreement: –

- 1. It’s too complex – The Financial Times stated, “In total, the process could involve nine committees and up to 143 votes cast.”

- It’s underfunded – The Single Resolution Mechanism, at Euro 55bln by 2026, is a drop in the ocean.

- It’s primarily a domestic affair, the union will be subject to national borders

- It will probably take at least five years to establish joint European liability.

Bruegel – Ending uncertainty: recapitalisation under European Central Bank Supervision – takes up the subject:-

http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/806-ending-uncertainty-recapitalisation-under-european-central-bank-supervision/

• Estimates of the recapitalisation needs of the euro-area banking system vary between €50 and €600 billion. The range shows the considerable uncertainty about the quality of banks’ balance sheets and about the parameters of the forthcoming European Central Bank stress tests, including the treatment of sovereign debt and systemic risk. Uncertainty also prevails about the rules and discretion that will apply to bank recapitalisation, bank restructuring and bank resolution in 2014 and beyond.

• The ECB should communicate the relevant parameters of its exercise early and in detail to give time to the private sector to find solutions. The ECB should establish itself as a tough supervisor and force non-viable banks into restructuring. This could lead to short-term financial volatility, but it should be weighed against the cost of a durably weak banking system and the credibility risk to the ECB. The ECB may need to provide large amounts of liquidity to the financial system.

• Governments should support the ECB, accept cross-border bank mergers and substantial creditor involvement under clear bail-in rules and should be prepared to recapitalise banks. Governments should agree on the eventual creation of a single resolution mechanism with efficient and fast decision-making procedures, and which can exercise discretion where necessary. A resolution fund, even when fully built-up, needs to have a common fiscal backstop to be credible.

The initial Asset Quality Review (AQR) of European Banks carried out in 2011 by the European Banking Authority proved to be a political embarrassment since almost every bank was found to be in relatively rude financial health: shortly before bailouts were required.

Breaking Views – Still time to undo EU bank stress test fiasco – November 2011 – sums up the problems with the previous stress tests eloquently: –

http://www.breakingviews.com/still-time-to-undo-eu-bank-test-fiasco/1616988.article

The test, which was blessed by last month’s ill-fated European summit, had two problems. First, it wasn’t stringent enough: the European Banking Authority concluded that Europe’s lenders needed an additional 106 billion euros, when the International Monetary Fund thought about twice as much was needed. The test has done little to restore confidence in the blighted sector. Banks are still unable to issue long-term unsecured debt, and have been increasingly thrown back on short-term support from the European Central Bank.

Second, the test encouraged deleveraging by expressing the capital requirement as a ratio and giving lenders eight months to get there. Given depressed share prices, many banks are anxious to avoid issuing equity. Instead they are trying to boost capital ratios by shrinking their balance sheets. This will almost certainly have the unfortunate side-effect of further suffocating the European economy, which is already on the edge of recession.

The current iteration of the AQR will, undoubtedly, have more “teeth” but these are shark infested waters where an ECB “health warning” might precipitate an ugly banking crisis.

The Peterson Institute – The European Central Banks Big Moment – December 2013 – elaborates:-

http://www.piie.com/publications/opeds/oped.cfm?ResearchID=2527

Europe’s banking union project has had many doubters since it started to be widely discussed in the spring of 2012. What is not in doubt, however, is its transformative nature. In June 2012, EU leaders chose—in a galloping hurry, as usual—to move towards the centralization of bank supervision across euro area countries, with this authority entrusted to the European Central Bank (ECB). The consequences have only gradually become apparent to most and represent both an opportunity and a risk.

The opportunity is to reestablish trust in European banks, reboot the pan-European interbank market, end dysfunctional credit allocation, and start reversing the vicious circle between bank and sovereign credit. In an optimistic scenario, the ECB’s 12-month process of “comprehensive assessment,” including an asset quality review (AQR) and stress tests of about 130 credit institutions covering 85 percent of the euro area’s banking assets, will trigger the triage, recapitalization, and restructuring that history suggests is a prerequisite for systemic crisis resolution.

The risk is that, if the assessment fails to be consistent and rigorous, the ECB may find its reputation so damaged that the credibility of its monetary policy—and the perception of Europe’s ability to get anything done—could be affected. After all, this exercise is unprecedented in scale and scope, which means the ECB has little prior experience. At the same time, the political fallout is potentially poisonous to most of the states concerned.

Thus, much is at stake in the balance sheet review, and the scene is set for an escalating confrontation between the ECB and member states in the months ahead. The ECB has pointedly made clear that it will form an independent judgment on the capital strength of the banks examined, without necessarily following the views of national supervisors.

A successful AQR and establishment of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM)—EU jargon for the handover of supervisory authority to the ECB—would have structural consequences. Europe’s national and local governments often use their leverage over the publicly-regulated banking industry for industrial policy purposes or to facilitate their own financing, a dynamic known to economists as financial repression.

Bruegel – Supervisory transparency in the European banking union – January 2014 – looks, in more detail, at the issues surrounding European bank regulation by the ECB, they acknowledge the need for greater transparency and highlight the dangers of a half-baked approach to a banking union: –

http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/807-supervisory-transparency-in-the-european-banking-union/

• Bank supervisors should provide publicly accessible, timely and consistent data on the banks under their jurisdiction. Such transparency increases democratic accountability and leads to greater market efficiency.

• There is greater supervisory transparency in the United States compared to the member states of the European Union. The US supervisors publish data quarterly and update fairly detailed information on bank balance sheets within a week. By contrast, based on an attempt to locate similar data in every EU country, in only 11 member states is this data at least partially available from supervisors, and in no member state is the level of transparency as high as in the US.

• Current and planned European Union requirements on bank transparency are either insufficient or could be easily sidestepped by supervisors. A banking union in Europe needs to include requirements for greater supervisory transparency.

I always find Bruegel comments useful , not only in terms of what should be done to move the “European Project” forward, but also as a guide to what the institutional response is likely to be should an EU proposal fail to be adopted. They conclude: –

Finding agreement on an EU legal change that requires the ECB and member-state supervisors to open their books to greater scrutiny will surely be a difficult task given the current diversity of practices and interests – eg banks, national supervisors – that benefit from this diversity.

But greater supervisory transparency will facilitate more efficient distribution of capital and increase market discipline. It will increase the legitimacy of actions that the regulator takes against banks. The European Union receives justified flak that there is a great distance between European citizens and the institutions that make decisions on their behalf. There is real suspicion of the financial sector and distrust that public money goes only to help out political friends. Transparency in terms of the data the supervisors themselves use to make decisions would allow the public, and more realistically the various interest groups one finds in civil society, to judge whether regulators did choose actions consistent with protecting the public interest. Such ‘fire alarms’ therefore represent one small step towards addressing the democratic deficit that most citizens think exists in Europe.

If such transparency is not possible, for purposes of increasing ‘output legitimacy’ more work should be done to strengthen the role of parliaments. For the European Parliament, the autumn 2013 interinstitutional agreement with the European Central Bank represents a good start. Under all current proposals, national regulators will continue to play an important role especially for any bank resolution. As discussed earlier, the German Bundestag gains the ability in 2014 to investigate specific banks as part of the national implementation of Basel III. Such parliamentary powers should become standard in all European Union member states. Moreover, such a procedure should be not only a theoretical power, but also one that is used.

Nationalist Backlash

In a more recent post this month – Peterson Institute – Calm Seas in Europe in 2014? – Jacob Funk Kirkegaard predicts that whilst 2013 was a year of relative calm for the Eurozone, 2014 may be a very different matter. As usual the driving force behind any change in sentiment will be political: –

http://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime/?p=4195

No major EU elections are scheduled in 2014. In Italy, a new electoral law is unlikely to be agreed upon before it takes over the rotating EU presidency in the second half of 2014. By tradition, countries in that position refrain from holding national elections. Rather, European Parliament elections in May will be the political highlight of 2014. As discussed earlier, there is a risk that angry voters will turn out and elect some colorful non-mainstream members to that body. Still, there seems little risk that the European Parliament will become a “Weimar Parliament” with a majority of anti-EU members. Instead the established European parties seem likely to prevail with a smaller majority, ensuring that Europe remains governable.

With their increased representation, the question of what the anti-EU parties want (aside from their daily parliamentary allowances) will arise. Much has been written about the alliance between Marine Le Pen, leader of the French National Front, and the leader of the Dutch Freedom Party Geert Wilders. But theirs is little more than a photo-op coalition, posing limited political risks. There are inherent limitations on the ability of nationalist parties to collaborate across borders.

The European Parliament elections, though, may also indirectly influence the choice of the next president of the European Commission. In an attempt to broaden the democratic appeal of the European Union, the European political parties have suggested that they each propose a pan-European spitzen-kandidat for the post and then let the European voters decide. Of course, this is a naked—if well-intended—power grab by the European Parliament, as the right to select the Commission president resides with the EU member states according to the EU Treaty. And they are unlikely to surrender this right. At the same time, it will be very difficult for the EU member states to ignore the winning side in the European Parliament election. The heads of states will hence likely be compelled to at least choose a new European President from the side of the political aisle that won the most votes in the election. Their selection power will thus be constrained…

Economically, the biggest event in 2014 will be the rollout of the ECB’s asset quality review (AQR) and stress tests of the euro area banking system, representing the opportunity to finally restore the soundness of Europe’s bank balance sheet. Failure to carry out a convincing review will threaten the region with Japanese-style prolonged stagnation and undermine the credibility of the ECB. The AQR/stress test is more important than the hotly debated single resolution mechanism (SRM) designed to close down or consolidate failing banks, finally agreed by the EU finance ministers in late December [pdf]. Only a successful AQR/stress test can avert the continuing fragmentation of credit markets and reduce the high interest spreads between the core and periphery. Assuming that the SRM can fix financial fragmentation is erroneous, and much of the related criticism of the complex SRM compromise is misplaced. Even an optimally designed SRM would not make euro area banks suddenly lend to each other again.

A more pertinent question is whether the SRM compromise makes it more or less likely that the AQR succeeds in 2014. For sure the envisioned SRM is far from perfect. It has an excessively complex structure, including a 10-year phase-in, and a multistage resolution process involving a resolution board, the European Commission, and the EU finance ministers in the ECOFIN (finance ministers’) Council. Parts of it are grounded in EU law and parts are to be embodied by a new intergovernmental treaty. Hopefully some of these kinks will be corrected in the ongoing final reconciliation negotiations on the SRM between the member states and the European Parliament. But writing off the SRM as unworkable just because it is complex is a mistake. The European Union of 28 member states works every day, despite breathtaking complexity. Moreover, in emergencies the European bureaucracy can be circumvented and a decision forced through in 24 hours.

The European political landscape may become more polarised in 2014 with right wing parties gaining ground in the European parliament.

The Economist – Europe’s Tea Parties – 4th January 2014 – looks at the rise of nationalist parties in Europe, making comparison with the US Tea Party Republican group, there are some similarities but the differences are more pronounced: –

… There are big differences between the Tea Party and the European insurgents. Whereas the Tea Party’s factions operate within one of America’s mainstream parties, and have roots in a venerable tradition of small-government conservatism, their counterparts in Europe are small, rebellious outfits, some from the far right. The Europeans are even more diverse than the Americans. Norway’s Progress Party is a world away from Hungary’s thuggish Jobbik. Nigel Farage and the saloon-bar bores of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) look askance at Marine Le Pen and her Front National (FN) across the Channel. But there are common threads linking the European insurgents and the Tea Party. They are angry people, harking back to simpler times. They worry about immigration. They spring from the squeezed middle—people who feel that the elite at the top and the scroungers at the bottom are prospering at the expense of ordinary working people. And they believe the centre of power—Washington or Brussels—is bulging with bureaucrats hatching schemes to run people’s lives.

The minority parties might seem largely irrelevant but voter apathy towards voting at European Elections gives European “Tea Parties” an opportunity to punch above their weight: –

Ultimately, though, the choice falls to voters themselves. The Tea Party thrived in America partly because a small minority of voters dominate primary races especially for gerrymandered seats. In elections to the European Parliament many voters simply do not bother to take part. That is a gift to the insurgents. If Europeans do not want them to triumph, they need to get out to the polls.

For an historical perspective on how the Eurozone might move towards closer unification the New York Fed – The Mississippi Bubble of 1720 and the European Debt Crisis – 10th January 2014 – offers some interesting observations. This is part of a series of articles called the “Crisis Chronicles” from Liberty Street Economics: –

http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2014/01/crisis-chronicles-the-mississippi-bubble-of-1720-and-the-european-debt-crisis.html

Austerity and Debt Restructuring

From summer 2012 through 2013 European equities performed well, with peripheral markets such as Greece and Ireland benefitting from the reduced risk of a Greek exit and single currency area breakup. Bond markets exhibited a similar response with higher yielding peripheral markets outperforming the core – see first chart above. 2014 may see these convergence patterns reverse as this article from the Council for Foreign Relations – Beware of Greeks Bearing Primary Budget Surpluses – points out: –

http://blogs.cfr.org/geographics/2013/12/04/greeksurpluses

.

.

.

.

.

Source: IMF

Things are looking up in Greece – that’s what Greek ministers have been telling the world of late, pointing to the substantial and rapidly improving primary budget surplus the country is generating. Yet the country’s creditors should beware of Greeks bearing surpluses.

A primary budget surplus is a surplus of revenue over expenditure which ignores interest payments due on outstanding debt. Its relevance is that the government can fund the country’s ongoing expenditure without needing to borrow more money; the need for borrowing arises only from the need to pay interest to holders of existing debt. But the Greek government (as we have pointed out in previous posts) has far less incentive to pay, and far more negotiating leverage with, its creditors once it no longer needs to borrow from them to keep the country running.

This makes it more likely, rather than less, that Greece will default sometime next year. As today’s Geo-Graphic shows, countries that have been in similar positions have done precisely this – defaulted just as their primary balance turned positive.

The upshot is that 2014 is shaping up to be a contentious one for Greece and its official-sector lenders, who are now Greece’s primary creditors. If so, yields on other stressed Eurozone country bonds (Portugal, Cyprus, Spain, and Italy) will bear the brunt of the collateral damage.

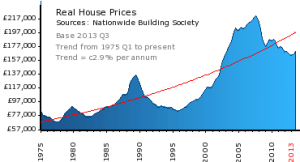

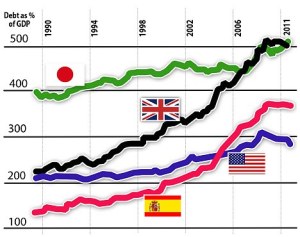

European debt restructuring meanwhile still has far to go but many EZ countries seem to think that being “developed” precludes the need to restructure and reform. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff produced a working paper for the IMF – Financial and Sovereign Debt Crises: Some Lessons Learned and Those Forgotten – December 2013 – which takes a global look at this subject in detail: –

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13266.pdf

Here’s the abstract: –

Even after one of the most severe multi-year crises on record in the advanced economies, the received wisdom in policy circles clings to the notion that high-income countries are completely different from their emerging market counterparts. The current phase of the official policy approach is predicated on the assumption that debt sustainability can be achieved through a mix of austerity, forbearance and growth. The claim is that advanced countries do not need to resort to the standard toolkit of emerging markets, including debt restructurings and conversions, higher inflation, capital controls and other forms of financial repression. As we document, this claim is at odds with the historical track record of most advanced economies, where debt restructuring or conversions, financial repression, and a tolerance for higher inflation, or a combination of these were an integral part of the resolution of significant past debt overhangs.

The paper follows on from research they have undertaken over the last couple of years including their seminal work – Growth in a time debt – NBER – January 2010 – which achieved considerable notoriety when an economics student discovered statistical errors in the paper – a short version is available here: –

http://www.nber.org/digest/apr10/w15639.html

Their new paper concludes: –

Of course, if policymakers are fortunate, economic growth will provide a soft exit, reducing or eliminating the need for painful restructuring, repression, or inflation. But the evidence on debt overhangs is not heartening. Looking just at the public debt overhang, and not taking into account old-age support programs, the picture is not encouraging. Reinhart, Reinhart, and Rogoff (2012) consider 26 episodes in which advanced country debt exceeded 90 percent of GDP, encompassing most or all of the episodes since World War II. (They tabulate the small number of cases in which the debt overhang lasted less than five years, but do not include these in their overhang calculations.) They find that debt overhang episodes averaged 1.2 percent lower growth than individual country averages for non-overhang periods. Moreover, the average duration of the overhang episodes is 23 years. Of course, there are many other factors that determine longer-term GDP growth, including especially the rate of productivity growth. But given that official public debt is only one piece of the larger debt overhang issue, it is clear that governments should be careful in their assumption that growth alone will be able to end the crisis. Instead, today’s advanced country governments may have to look increasingly to the approaches that have long been associated with emerging markets, and that advanced countries themselves once practiced not so long ago.

Germany’s slowing growth and potential banking crisis

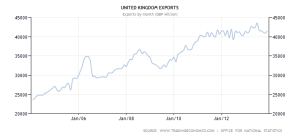

Meanwhile, Germany, which has benefitted economically from the painful Hartz reforms of the early 2000’s may be losing momentum.

Peterson Institute – Making Labor Market Reforms Work for Everyone: Lessons from Germany – sets the scene, highlighting how labour reform in Germany has given the country a significant competitive edge: –

http://www.piie.com/publications/pb/pb14-1.pdf

…First, Germany has the best functioning labor market among large economies in Europe and the United States. Second, German wage restraint is of a relatively limited magnitude compared with most euro area countries and hence fails to explain the uniformly large intra–euro area unit labor cost divergences between Germany and other members after 1999. Third, total German labor costs per worker continue to exceed costs in other major EU countries and the United States. Fourth, Germany’s recent labor market revival has not come about through the expansion of predominantly low wage jobs. Fifth, the expansion of mini-jobs in Germany since 2003 has overwhelmingly taken place as second jobs. And sixth, the successful reliance on kurzarbeit programs in 2009 was not an innovation but rather another instance of labor input adjustment in favor of “insider workers” in Germany.

I’m indebted to Quartz.com for the table below which shows German exports and imports by region. Within the Eurozone the two components are fairly balanced but this disguises country specific imbalances, for example, for the first 10 months of 2013, Germany ran a surplus with France of Euro 30bln but a deficit with the Netherlands of Euro 15bln.

.

.

.

.

Source: Quartz.com

The Economist – Die grosse stagnation – 30th November 2013 – paints a rather different picture of the risks ahead for Germany – once again these risks are political in nature, but their principal concern is that the recent coalition deal looks set to reverse a number of these successful reforms: –

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21590903-germanys-proposed-new-government-set-turn-motor-europe-slowcoach-die-grosse

…That is because Germany’s economy has been living off past glory—especially “Agenda 2010”, a series of reforms launched in 2003 by Gerhard Schröder, Mrs Merkel’s predecessor. But it is running out of puff. Labour productivity has grown less than half as fast as Spain’s over the past ten years; and its overall rate of public and private investment, at 17% of GDP, has fallen by more than a fifth since the euro was introduced. No European country has carried out fewer reforms than Germany since the euro crisis began.

… The coalition’s 185-page “treaty” was a chance to launch a new reform agenda. Instead, its proposals are a mixture of the irrelevant—charging foreigners to use German motorways—and the harmful.

…The coalition’s pension policy seems even more retrogressive. These days, most advanced economies are expecting longer-living people to be longer-working, too. But the coalition wants the pension age, raised to 67 in the previous grand coalition, to be moved back down again for specific groups, in some cases to 63. France’s president, François Hollande, was rightly mocked, not least by Mrs Merkel, for a similar ploy. Now the woman who has lectured the rest of Europe about the unsustainability of its welfare spending will follow down the same spendthrift road.

…The impact on this coalition on the rest of Europe would not be all bad. One bonus is that, for all its primitive economic policies, the SPD seems keener to support some basic reforms such as the creation of a banking union. But that will count for little if Germany, the motor of Europe’s economy, stalls. And, in the light of the coalition agreement, that is a real danger.

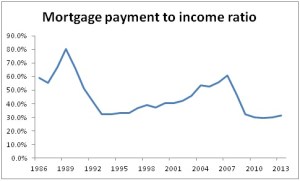

After a strong performance by European Equities and peripheral government bonds in 2013, the prospects for 2014 may be less sanguine, though I’m not bearish at this stage. The principal market risk is likely to emanate from the European banking sector. One example of this, concerns shipping. The chart below shows the Baltic Dry Freight Index month end values from 1985 to end December 2013 – it’s worth noting that the BDI has plummeted this month leading many commentators to predict a global economic downturn.

.

.

.

.

Source: Bloomberg

Over the past ten years the price of “Dry” cargoes has soared and plummeted. During this cycle European banks, German ones in particular – abetted by favourable German government tax treatment – moved aggressively into the shipping finance sector; it is estimated that German banks are currently the financiers behind more than 40% of the world container shipping fleet. These shipping loans were often repackaged and sold on to high net worth investors but, rumour has it, the majority of these investments carried a “principal guarantee”. The ships, meanwhile, are no longer competitive due to improvements in fuel efficiency since the mid 2000’s. The banks are effectively left long “scrap metal”.

Moody’s gave an estimate last month for German banks impairment due to shipping loans of US$22bln for 2014, they went on to state: –

Germany’s eight major ship financiers have lent a total of 105 billion euros to the sector, a fifth of which are categorized as non-performing…

We expect the extended downward shipping cycle to cause rising problem loans in the shipping sector during 2013-14, requiring German banks to increase their loan-loss provisions. This will challenge their earnings power.

Here is the Reuters article for further detail: –

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/12/10/moodys-shippingbanks-idUSL6N0JP2CV20131210

I wonder whether the ECB’s AQR will uncover the extent of this problem. Last Autumn S&P estimated European banks had a funding gap of Euro 1.3trln as at the end of 2012. My guess is that this is understated: shipping is just one sector, the “quest for yield” is industry wide.

EZ Money supply growth and rising peripheral debt

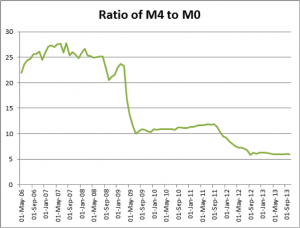

Another headwind facing Europe is the weakness in money supply growth. In 2012 EZ M3 was growing at above 3%, it dipped below 3% in H1 2013 and below 2% in H2 2013.

.

.

.

.

.

Source: ECB

The ECB CPI target of 2% is roughly consistent with M3 growth of 4-6%.

The Telegraph – Eurozone M3 plunge flashes deflation alert – Novemebr 28th 2013 –

takes up the theme of potential deflation:-

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/10481773/Eurozone-M3-money-plunge-flashes-deflation-alert-for-2014.html

The European Central Bank said M3 money growth fell to 1.4pc from a year earlier, lower than expected and far below the bank’s own 4.5pc target deemed necessary to keep the economy on an even keel.

A rather more extreme view is expressed by Andrew Cullen – Europeans Looking To Inflate Their Debts Away – Mises Institute – 12th November 2013

http://mises.org/daily/6581/Europeans-Looking-To-Inflate-Their-Debts-Away

How does a reduction in consumer price inflation become “deflation”? How does a minor improvement in the purchasing power of consumers become a problem for liquidity in the financial markets? Austrian-economic thinking, which understands that new money is never neutral in its effects, offers insight:

[T]he crux of deflation is that it does not hide the redistribution going hand in hand with changes in the quantity of money …[4]

European politicians and central bank policy-makers are concerned not about consumer price reductions but about real reductions in the money supply as such reductions would force governments to abandon permanent budget deficit monetization. That is why they maintain a monopoly over the power to create money and they like to control where money enters the economy. Politicians use these advantages in two ways.

First, they are all, with the sole exception of the Bundesbank, “inflationists” when it comes to monetary policy. Inflation (that is, an increase in the money supply) steadily reduces the purchasing power of a fiat money and, in parallel, eases the burden of debt repayments over time as nominal sums become progressively of less relative value.

Such price inflation benefits debtors at the expense of creditors. Hence, for highly indebted Eurozone governments, price inflation is the perceived “get out of jail” card, permitting them to meet their debt obligations with a falling share of government expenditures.

Second, at least amongst the political elites in the “PIIGS” (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain) and in France, they espouse “reflation” plans using the ECB’s money-creation powers which would ratchet up to another degree inflation of the money supply, monetization of government debt, and increases in total government debts; and thereby protect and enhance the economic power and privileges of governments and the state.[5]

Yet growth of PIIGS governments’ debts as a proportion of GDP (Table 1) have now crossed above the critical 90 percent ratio advised by Rogoff and Reinhart as being the threshold above which growth rates irrevocably decline.[6]

Table 1. Gross Government Debt as Per cent of GDP 2008-14 for the Eurozone and selected member countries (Adapted from: IMF Fiscal Monitor: Taxing Times, p16. October 2013)

2008 2010 2012 2014 (forecast)

Eurozone 70.3 85.7 93.0 96.1

Spain 40.2 61.7 85.9 99.1

Italy 106.1 119.1 127.0 133.1

Portugal 71.7 94.0 123.8 125.3

Ireland 44.2 91.2 117.4 121.0

There is another potential problem: European commercial banks may be too fragile to fulfil their allotted role. ECB President Mario Draghi himself has initiated another round of stress testing of European banks’ balance sheets against external shocks, a sign that the ECB itself has doubts about systemic stability in the banking sector. But this testing has hardly begun. Here are four risk factors in play:

First, there has been large-scale flight of deposits from banks operating within the PIIGS’ toward banks of other Eurozone countries,[7] as well as outside the Eurozone entirely. This phenomenon is caused by elevated risk of seizures, consequent upon the forced losses on bondholders at Greek banks and the recent “bail-in” of depositors at the Bank of Cyprus.

Second, many PIIGS’ domestic banks still hold on their books bad loans arising from the boom years (2000-2007). Failure to deleverage and liquidate losses is prolonging the banks’ adjustment process.

Third, they already hold huge quantities of sovereign debt (treasury bonds) from Eurozone governments from previous rounds of buying. Banks have had to increase their risk weightings on such debt holdings as Ratings Agencies have downgraded these investments to comply with Basel II. This constrains their forward capacity for lending to these governments.

Fourth, there is concern for rising interest rates. Since the famous “Draghi put” in July 2012, real rates remain low and yields on PIIGS’ sovereign bonds fell back closer to German bunds. But this summer yields on US Treasury bonds with long maturities started to rise on Fed taper talk.[8] Negative surprises knock confidence in the international bond markets. The risk of massive losses should bond prices drop is one that the European-based banks cannot afford given their still low capital reserves and boom phase legacy of over-leveraging.

Implementation impediments aside, a new phase of aggressive easy money policy from the ECB is both probable and imminent.

[4] J.G. Hülsmann, Deflation & Liberty (2008), p. 27.

You might also enjoy Andrew’s blogsite where he also speculates about large scale asset purchases from the ECB: –

http://www.thecantillonobserver.com

European equity and bond market prospects for 2014

This brings me neatly to what you may consider a rather contrarian view of European equities and bonds. So far this article has focussed on the negative headwinds which many commentators expect to undermine confidence in financial markets, however, I’m reminded of some sage words from the “Sage of Omaha” – the quote below comes from an interview/speech which Warren Buffet gave in July 2000 at the Allen & Co, Sun Valley corporate gathering, reported here by Fortune/CNN: –

http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2001/12/10/314691/

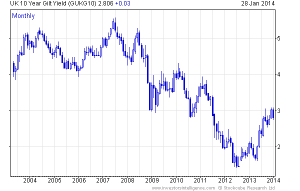

In economics, interest rates act as gravity behaves in the physical world. At all times, in all markets, in all parts of the world, the tiniest change in rates changes the value of every financial asset. You see that clearly with the fluctuating prices of bonds. But the rule applies as well to farmland, oil reserves, stocks, and every other financial asset. And the effects can be huge on values. If interest rates are, say, 13%, the present value of a dollar that you’re going to receive in the future from an investment is not nearly as high as the present value of a dollar if rates are 4%.

So here’s the record on interest rates at key dates in our 34-year span. They moved dramatically up–that was bad for investors–in the first half of that period and dramatically down–a boon for investors–in the second half.

Since short term rates are close to zero and central bank buying of government bonds has flattened yield curves in most major markets, surely the risk has to be that government bond yields have an asymmetric upside risk? Well, yes, but only if investors lose all confidence in those “risk-free” government obligations. Added to which – what is the correct size for a central bank balance sheet – $4trln or $400trln? When measured in balance sheet expansion terms the ECB is far behind the curve; they have availed themselves of the aggressive quantitative easing of other central banks to exert internal pressure on profligate EZ countries, cajoling them to structurally reform. I believe this austerity has largely run its course, but, as the AQR, is likely to show, it has left the EZ financial system in a weak position.

European bond convergence between the core and periphery continues as the table below (15/1/2014) from Bloomberg shows : –

| Europe |

|

Yield |

1 Day

|

1 Month

|

1 Year

|

|

| Germany |

|

1.82% |

+1 |

-1 |

+24 |

|

| Britain |

|

2.86% |

+3 |

-4 |

+84 |

|

| France |

|

2.47% |

+1 |

+4 |

+34 |

|

| Italy |

|

3.88% |

+1 |

-21 |

-33 |

|

| Spain |

|

3.82% |

+1 |

-28 |

-120 |

|

| Netherlands |

|

2.13% |

+1 |

-1 |

+43 |

|

| Portugal |

|

5.25% |

0 |

-77 |

-104 |

|

| Greece |

|

7.67% |

0 |

-95 |

-388 |

| Switzerland |

|

1.18% |

+1 |

+22 |

+56 |

|

European stock markets are making new highs – although EuroStoxx 50 is still some way below its 2008 peak, unlike the S&P. EUR/USD continues to regain composure after the fears of an EZ break-up in the summer of 2012. In this environment I see no reason to liquidate long positions in European equities and higher yielding peripheral bond markets. If US Equities turn bearish and US bond yields rise abruptly, as they did in 2013, then I would expect the ECB to provide their long overdue support. However, a precipitous decline in EUR/USD is cause for concern as this may herald the beginning of another Eurozone crisis – whilst I anticipate some of the above issues will surface during 2014, the “Draghi put” still offers significant protection, whilst the Peterson Institute – Why the European Central Bank Will Likely Shrink from Quantitive Easing – January 15th 2014 – makes a strong case for the ECBs hands being tied: –

http://blogs.piie.com/realtime/?p=4208

I still believe European markets represent a “hedged” exposure to the continued bullish trends in major market equities and higher yielding bonds – the market always prefers to travel than to arrive.